In Berlin, the neighborhoods of Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain are governed by a single administration. The two Kieze (neighborhoods) together are called Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, inventively, and manage within about eight square miles to contain some of Berlin’s most iconic landmarks: the East Side Gallery, where murals coat a swath of the former Berlin Wall, and Berghain, a former bunker turned gay nightclub turned punchline about exclusive door policies. On a given day along the Warschauer Straße bridge, which connects the two areas, one is likely to see — peppered among the buskers, street artists, and occasional pram pushers — bleary-eyed and leather-clad twentysomethings staggering out of nearby clubs and white, dreadlocked punks sitting with cardboard, hand-lettered signs. According to the city of Berlin’s website, “this district is not just the coolest in Berlin, but the hippest location in the entire universe.”

Leaving aside that a city government’s acknowledgment of a neighborhood’s “cool” factor is essentially its death knell, the transformation that has occurred in both Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain — regions that once bordered the West and East sides of the Berlin Wall, respectively — is undeniable. Somewhere along the way, Berlin became known as Europe’s answer to the U.S. tech boom: “Silicon Allee,” some called it. Inspired by the city’s long-standing hacker culture and creative ethos, start-ups and verified Silicon Valley magnates alike swarmed to fill Berlin’s graffitied former squats, aptly juxtaposing the two worlds interminably entwined in this once divided city.

That separation, of course, came following Germany’s defeat in World War II. The country was split up between the four allied forces that had overtaken Hitler’s army (the U.S., the U.K., France, and the U.S.S.R.), including 20 districts in Berlin alone. These Berlin districts, established in 1945, carved up the city between the capitalist control of the Global North (West Berlin) and the increasingly stringent regime of Soviet communism (East Berlin). On a single day in 1961, the Soviets erected what would become a symbol of the fight between capitalism and communism: the Berlin Wall, a 96-mile stretch of reinforced concrete that effectively barred contact between East and West Berlin, separating families and loved ones overnight, impassable and seemingly insurmountable.

The Wall unofficially fell on November 9, 1989, and thus it’s now been down for longer than it once stood. Still, Germans today locate an ideological divide between East and West. The overarching (stereotypical) differences seem to be that West Germans, coming from prosperous cities like Cologne and Bonn and regions like Bavaria, are considered to have old-money European values and to be internationally traveled and fluent in English, while East Germans, from industrial cities like Leipzig and Dresden, have been financially oppressed and culturally marginalized.

Berlin, which has always been the meeting point of East and West Germany, now finds itself in the ideological lurch between the city’s seemingly interminable attractiveness to massive, international Big Tech corporations and the long-standing anti-capitalist tendencies intrinsic to the East.

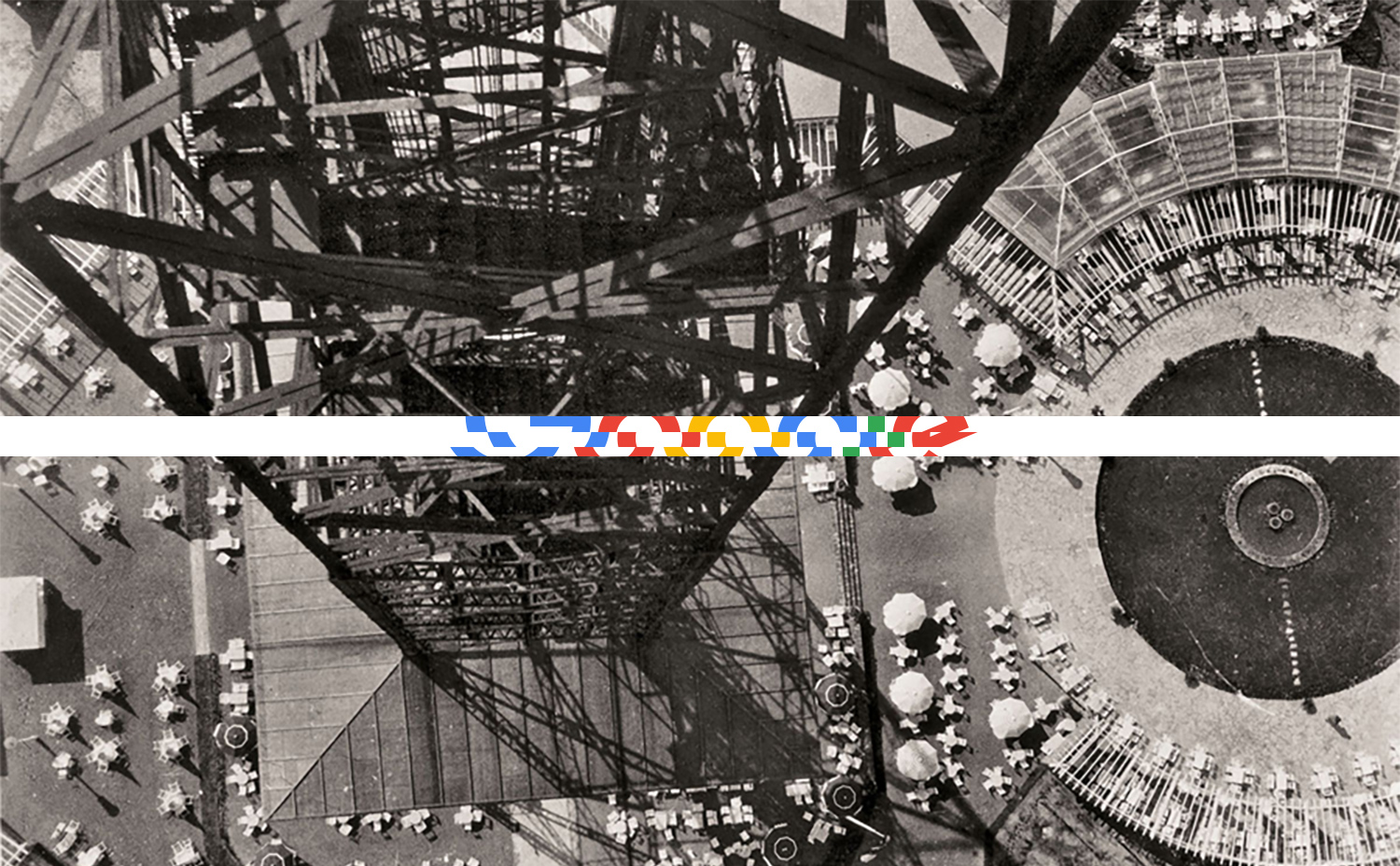

In October 2018, then, international outlets and activists alike were taken aback to see that activists in Kreuzberg had successfully pushed out one of the city’s most prominent new projects: a Google campus, the seventh of the company’s worldwide “campi,” with siblings in tech-savvy (already gentrified) cities like San Francisco and London and financially precarious ones like Warsaw. The activists’ victory, hard won through weekly protest, partisan publications, political pressure, and glittery banners, resonated as a David-beats-Goliath-style unexpected victory for the gentrifying city in the Google age. Today, these organizers are now mobilizing again to protest another major Big Tech incursion, a massive Amazon location directly between Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain, right behind the Warschauer Straße bridge.

In

a 2018 report conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, experts concluded that there were immigrants from more than 180 nations living in the city. These immigrants, expats, and refugees — termed accordingly (though unofficially) based on the migrant’s nationality, class, and reasons for moving — comprise close to one third of Berlin’s total inhabitants. According to this report, Berlin’s population grows at a rate of almost 50,000 new citizens annually.

Being one of the “expat” class, I feel primed to comment on our demographic: young and untethered, either an artist (read: freelancer and/or under-the-table babysitter) or an employee who — more likely than not — loathes their nine-to-five at one of Berlin’s many touted start-ups. Many expats have advanced degrees, and many are enrolled in universities in Berlin to at least nominally continue their studies — a favorable option for a visa, as many know, as education is free and students can take up to seven semesters to submit their theses, with a bolster year postgrad to seek employment in their selected field. Some expats don’t speak, or even learn, German, and it’s pretty easy to see why: Despite having been in and out of German courses for the last two and a half years and having achieved a pretty comfortable level of fluency, I still predominantly work and almost exclusively socialize in English.

We come from all over the place: from global capitals like London, Paris, Melbourne, and New York to cities where work is harder to find and money is sparse, like Kraków, Rome, and Athens. For all of us gentrifiers, from the young urbanites to the tech start-ups, the draws are the same: Berlin’s culture, cheap rents, and unconventionality. For all of us, there is a tantalizing sense of some kind of vacuum in Berlin — a chasm of impossibly open space, of the ever elusive blend of urbanity and anti-capitalist freedom, emphasized with the sweet promise of successful democratic socialism — hovering in that void between the cool and the crumbling, the romantic notion of a city defined by its persistent rebelliousness instead of its acquiescence.

Expats

are an ouroboros of sorts, swallowing our own tail: eagerly escaping our suffocating monocultures, the real challenges of living in cities or countries without such generous provisions for their citizens, all in the aim of something “other” — and yet, in the language we use to communicate, the hodgepodge liberal leftism of our community spaces, and the reconfiguration of our urban landscape we inevitably recreate the same world from which we came. We come here, in other words, changing the city, and then decry its changing, undertaken by some impossible, invisible power: international elites, techno-capitalism. Like much of living in Berlin, to be a citizen-expat here is to live in the lurch between hope and heartbreak. Which fights are ours to fight? Where are we overstepping?

Among other jabs, critics of the ongoing anti-gentrification activism in Berlin have noted that these protestors have been less vocal about Google’s existing office in Mitte and Amazon’s existing locations in Charlottenburg. The determined activists with whom I spoke in Kreuzberg were similarly uninterested in Elon Musk’s plans to open a new Tesla factory in Brandenburg, a comparably rural and right-wing area surrounding the city of Berlin. Here, it is important to note that I don’t mention this selective focus as a means of casting aspersions on their activism but rather seek to explore it as an apt representation of the two minds still at odds in contemporary Berlin and the ongoing lineage of the Berlin Wall, even as it affects international city residents (and comparably recent transplants) like myself.

Many local theorists have declared Berlin long lost to the wave of capitalism that has rushed in, welcomed by factions of the city government with open arms, and as a still fairly new transplant they’d likely argue that I don’t have the experience to say otherwise. Berlin does behold both possibilities of techno-capitalism and democratic socialism: With ongoing plans for a massive Amazon building in the city, leftist government officials also officially passed a citywide rent freeze for the next five years, encouraging citizens to reclaim the equivalent of $2.75 billion in back pay from landlords who have overcharged them. Living through any transitional moment one struggles to locate the point on the event timeline at which one falls: Are we near the end of something? Or could we still be at the beginning?

To

walk through most neighborhoods in Berlin is to brush up against the overlapping edges of unruly public spaces and the bourgeois monocultural staples that have come to saturate most major cities: white-walled cafés with wooden cubes for seats, overpriced coffee, boutique shops offering scented candles and thin gold-wire mobiles, spinning classes. These material shifts represent, even in Berlin’s more notoriously alt neighborhoods, like Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain, the change to the city both demographic and ideological, as start-up — and, more painfully, Big Tech — culture has moved in.

Rents, of course, have skyrocketed: Today, the 85 percent of Berlin residents who rent their apartments (rather than owning them) pay more than twice what they did in 2004. City officials themselves have been historically, and characteristically, undecided about their stances on subsidized or privatized housing.

After the reunification of East and West Berlin in the early 1990s, Berlin officials began to sell the city’s once socialist infrastructure to private businesses. During this time, the city’s government privatized its electricity and water supplies, followed — most significantly — by the vast privatization of urban housing in 2004. Much of this housing went to Deutsche Wohnen, a subsidiary of Donald Trump’s longtime lenders, Deutsche Bank. In recent years, Berlin officials have flip-flopped on their pro-business position, reclaiming the city’s water supply in addition to establishing rent control for the next five years.

I met first with Fabian, a community activist and longtime Kreuzberg resident who lived a number of meters away from Google’s planned new campus. Fabian, who has lived in Berlin since he was a young teenager, has been an activist for decades: first an antifa activist against neo-Nazis (“more in East Berlin, than here in Kreuzberg,” he explained) and now as an organizer with his neighbors, a typically older set of Berliners who held their meetings in German. As Fabian described, the protests against Google — and the gearing up protests-to-be against Amazon — consist of groups with many minds. His organization, No Google Campus, was focused on the risks of rent control and the cultural threat a Google campus posed to the neighborhood, including the likely potential that Google’s Kreuzberg incursion would inspire more start-ups to do the same. Like many of their neighbors, Fabian and his cohort are planning to continue the fight against Amazon as Bezos plots his move deeper into Berlin.

Why not Charlottenburg? Or Brandenburg? I asked him, and Fabian looked confused. “It doesn’t affect me,” he answered plainly.

When I met with Larry, a representative of another Kreuzberg activist group, Fuck Off Google, he was similarly nonplussed by my curiosity about the outcry (or lack thereof) in Charlottenburg, Mitte, and Brandenburg. Larry is a pseudonym: Representatives of Fuck Off Google prefer a cheeky use of the name of the cofounder of Google Larry Page when speaking to the press, and, as was clear in our interview, his — and their — privacy is sacred. In addition to his use of the group’s collective pseudonym, Larry also abstained from referencing their preferred meeting site by name, and alluded, at one point, to one friend who so values her privacy she possesses no phone or email address at all: “If I want to meet her, I write a note that I put in a box, I know where to find that box, and she’s always there on time.”

Unlike No Google Campus, Fuck Off Google is more broad and theoretical in its aims, evidenced both through our lively conversation — which swerved in and out of history, activist anecdotes, and broader musings on the future of techno-capitalism — and the organization’s website, which offers materials and information in both German and English not merely about the Berlin protests but also about larger themes of anti-surveillance and the possibility of a liberated Internet.

“You know, you’re asking me a very centrist-left question right now,” Larry admonished me, grinning. First, as he noted, it’s inaccurate that activists have been wholly silent about Google’s preexisting Mitte location — and, as I found after some research, activists have been similarly mobilized in Charlottenburg against Amazon as well. Anyway, he explained, Mitte is “lost. For fifteen years now.” The Berlin Kiez that housed both East and West Berlin simultaneously, which used to be ground zero for the Berlin counterculture, now hosts all official government buildings, glitzy shopping, and high-profit business. By contrast, Charlottenburg — an old-money neighborhood in West Berlin that has been affluent at least since Christopher Isherwood wrote Goodbye to Berlin in the 1930s — is “bourgeois,” and has been for a long time. In other words, for big business to migrate to Charlottenburg is business as usual, a normal continuation of the neighborhood’s preexisting capitalist values from before the Wall stood.

Alternately, Kreuzberg, Larry pointed out, has a long history of antiestablishment activism that has successfully managed to preserve the integrity of the unconventional area.

Brandenburg, then, becomes something of an anomaly, falling outside the urban paradigm of the crux wherein Fabian’s and Larry’s activisms meet. Both Fabian and Larry agreed that the proposed Google Campus and Amazon locations posed a threat to the unique flavor of Kreuzberg, the authenticity of their beloved neighborhoods, and, for Larry, the privacy of its inhabitants. Interestingly, at one point Fabian noted a potential reason for his disinterest in Brandenburg: “It’s a little bit ignorant,” he shrugged, with a small blush, “but I’m more often in cities like London than in Brandenburg. It’s not — my game.”

Are the residents of Brandenburg not entitled to, or deserving of, those same protections? Perhaps in an economically challenged area, one with a more conservative outlook, these are not the citizens’ concerns. And as for more broadly focused organizations like Fuck Off Google, which makes a point of standing against both local gentrification and universal issues of surveillance and data mining, it could be seen as an infraction for an outside organization to assume the political stance of another and intervene — that is to say, if residents of Brandenburg don’t mind a Tesla factory, then activists in Kreuzberg shouldn’t speak on their behalf. But by the same logic, perhaps, are expats like myself, or like some of the members of Fuck Off Google, not entitled to stand against Big Tech corporations seeking to land in our mutually claimed city, Berlin?

Ultimately, the disparity seemed to me to indicate an ongoing clash not merely between the values of East and West Berlin but of the growing divide between rural and/or economically challenged communities and urban, left-leaning cities. In effect, such a schism raises — among other things — an uncomfortable distinction between those with the means to challenge such incursions, and those without.

As

Fabian indicated in his reference to the likelihood that he would go to London more often than to neighboring Brandenburg, those united against Big Tech in urban centers have tapped into an international network of anti-gentrification activists. The result is an interesting merging of hyperlocalized gentrification battles in western capitals, bolstered by a transnational activist network.

According to Larry, the successful anti-Amazon protestors in Queens collaborated via chatroom discussions with the Berlin activists — conversations in which both parties “exchanged tactics for many hours, [and sent] love and solidarity.” In fact, Larry mentioned that some New York activists ended up coming to Berlin, passing through the Fuck Off Google meeting headquarters and swapping materials. Similarly, Fuck Off Google and activists in Toronto working against a proposed Google “Sidewalk Labs” have publicly acknowledged solidarity with one another’s movements, and Erin McElroy, a prominent anti-gentrification, anti–Big Tech activist in San Francisco participated in a Berlin panel facilitated by No Google Campus.

Toward

the end of our conversation, I asked Fabian if he felt hopeful about the future of Kreuzberg. He thought for a while, beginning his sentence a few times over as he carefully chose his words, sometimes slipping into German. “I think — yes, aber — I think, um, you can deal with some problems of gentrification, with others — that’s a problem that — ich finde sätze — the wrong question. I think . . . when . . . something affects you . . . then you have to do something. And you can win, you can lose, or — or change a little bit, and that’s the motivation, and not to say, oh, the future, and then it’ll all be great. That’s for religious people.”

Similarly, Larry — though innately optimistic about the community activism of Kreuzberg and the strength of its will — darkened as he contemplated the future more broadly. He described the shift that happened in the Internet — that what had once been “a window of opportunity for . . . Internet-based connectivity, socialization, and practices that would truly liberate, and emancipate, and enable to participate” had actually been reclaimed and manipulated by Big Tech, irretrievably. We as a culture had been, as he described it, the “useful idiots.” Pointing to my iPhone, which sat between us and recorded our conversation, he remarked, grimly: “We’ll never take control of a device like this. Never, ever, ever.”

The

well-documented history of Berlin — what some would even call the city’s soul and selling point — continues to be written. During the time I was working on this piece, significant decisions pulled toward the opposite chambers of Berlin’s ambivalent heart: A short time before rent control was announced, Griessmühle, a beloved local club, was forced to close after a long-standing fight with a developer eager to “extensively renovate” its grimy Neukölln location. Friends lamented the closure via social media, sharing petitions, inviting us to protests. One friend in particular wrote something to the effect of: I already lived in London and saw this happen there. Can Berlin be saved?

Certainly, the belief of many is that the fight against techno-capitalism in Berlin has already long been lost. What is more realistic, however, is that Berlin, a city with a long-standing history of radical opposing ideologies forced together, has been quashed and reborn endlessly over the last century. The insistence by city residents on preserving the “old Berlin” — chanted by many of us who never knew it, and who, perhaps, unintentionally helped to destroy it — has turned Berlin’s mythos into a rallying cry in a battle that manages to be both general and specific, local and global. In a city that has for decades stood at what felt like the end of history, Berliners fight for the maintenance — or, perhaps, the creation — of a city, our city.