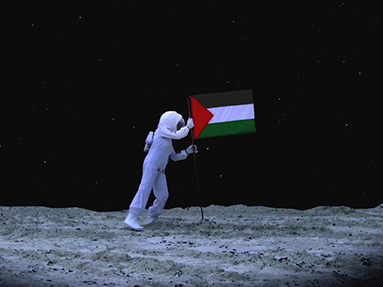

Two filmmakers do battle with the hegemony of the Western nation-state in the weightlessness of space.

Larissa Sansour and Frances Bodomo’s wildly creative work takes control of the geopolitical valences of spaceflight and blasts off with them, sending their avatars into the celestial space normally controlled by the giants of earthly might. Sansour’s 2009 A Space Exodus stages a lunar landing under the auspices of the Palestinian Space Program, planting a flag in the night sky and highlighting the stakes of a return to Jerusalem as more than a moonshot. In Bodomo’s 2014 Afronauts, the real-life Zambian space mission rushes to completion contemporary with the US Apollo 11 launch. Even though their work has been shown together at times, somehow their parallel trajectories missed each other in transit. We put them into email conversation with each other to see what perspectives they had both gained from looking at the stars at such an angle.

Frances: I would love to hear you speak about how space relates to landlessness, homelessness. Was this a part of your process? I was especially struck by, “Jerusalem, we have a problem,” as a wondrous reclamation of land, later to be lost as she tumbles deeper into space. Very poignant.

Larissa: There is a saying going around in Palestine for many years now that goes: “It is easier to reach the moon than to reach Jerusalem.” This is unfortunately the state of affairs in occupied Palestine now. I was born in Jerusalem, but I am not allowed by the state of Israel to enter it. For most Palestinians, traveling from one Palestinian city to another is becoming if not extremely hard, sometimes impossible. A Space Exodus references Armstrong’s famous words and contextualises them in the Palestinian struggle for statehood. In the film you see me try to get in touch with Jerusalem from my spaceship but I never hear anything back. I get lost forever in space. There is a direct comment on Palestinians being forever stuck in limbo, in a space of statelessness.

Are you, Frances, interested in changing the meaning of certain symbols and elements by placing them in a context that they are not usually associated with?

You’re right in calling these technological markers—the lab, the rocket, the space suit, the facility—symbols. Functionality considered, this is still an iconography: We endow technological validity to smooth, clean, white lines. Already we see why the iconography is dangerous. I often say that the Wright Brothers were just experimenting with sticks and tarp in a field for so long.

I’m not interested in changing symbolic meaning, necessarily, more in questioning and playing with them, busting open their rigid falsehoods, allowing them to be mutable things. It was important to enter the space of the jerry-rigged, the rinky-dink. To bring science out of the lab and into the shantytown. We’re looking at this rocket, this spacesuit, and thinking, “like … really?” But that’s why I love fiction, I love emotional tension. In that space, we watch on. Away from validity and properness, we enter intrigue. I mentioned the near-impossible earlier, and it was very important to sit in this in-between space, this small gap of, “but maybe they could.” We pit the rigid validity of “inspired by true events” against the obvious holes in the rocket.

My goal was to move the question away from “will they make it or not?”—this is a space film in which we never see space. Instead, that’s in the back of our minds as we’re asking: Why are they doing this? Who is this girl? How did they get here? We mine their psychology as opposed to their situation. I like being asked to mine the psychologies of characters I don’t understand.

I like these narrative spaces a lot, when you add a certain emotional crisis to a symbol. You can shift discourse/perspective, attack oppressive narratives, viewpoints, you go out of the idea-space and into the belly. I’m not there yet, but I want to keep exploring these spaces.

I like your playful approach to space iconograpy (the shape of the space shoes especially). What struck me most, though, was the music, because there it was playing with the myths we have created around space (rather than the more technical space suit and “Houston, we have a problem”).

The music mimics a 5 minute stretch from Stanley Kubrick’s A Space Odyssey, but is interpreted in Middle Eastern Arabesque undertones. The orientalist shoes and music question what a Palestinian space triumph would appear to the world outside it, and is of course colored by the Western gaze. The oxygen tank is a bit more feminine, as are the curls on the suit, and the whole space conquest in the film underlines “otherness.” The people who are usually the subject of news reports and diplomatic initiatives instead become the commentators. No longer the underdogs, they stand at the same level as the rest of the world’s media and power-players. The work foregrounds an unspoken absence.

Talk about “exodus” versus “odyssey.” I love that! I’m thinking of odyssey as adventure (and even a journey home, re: Odysseus) versus exodus as a departure. How does the idea of space exploration shift for you?

I really like this observation. It is true that the two are somehow conflated in concept for me. I think the Palestinian experience is a multi-layered one and it is hard for me to detach the geographical from the diasporic condition of Palestinians. I think that art has an inherent malleable quality that allows a more nuanced discourse to take place. I always find it fascinating when art manages to do that. In A Space Exodus I wanted to frame Palestinian iconography in a universal context, one in which we associate Palestine with technological progress or scientific discoveries. So the Palestinian Space Program is an imagined and utopian space. Landing on the moon is a hopeful and triumphant moment. Yet the sadness of Space Exodus is also implicit in the contemporary reactions to the US space program, from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey to Tarkovsky’s Solaris and even David Bowie’s “Space Oddity.” The moon landings reflected a widespread anxiety that, in leaving Earth, we risked never being able to return home again. Yet because this anxiety is universal, the pain of the real, forced exodus of the Palestinians is doomed to remain a private grief, forgotten by the rest of the world.

Did you work on this project having a film audience in mind specifically or were you also interested in having it shown in an art context?

This is a narrative film, interacting with and playing with traditional narrative form. I like cinematic spectatorship, and I tell stories for that space. Tension rises when you realize you’re more than halfway through a film and they’re still continuing on with the mission. I also tend to supply factual information after the emotional moments. It requires attention to the details in a frame.

Audience and point-of-view are my biggest considerations as I move from the short film to the feature. The short is ultimately framed by the American launch: “16 July 1969. America prepares to launch Apollo 11. Thousands of miles away, the Zambia Space Academy hopes to beat them to the moon.” I did this because I was being honest about my audience: Largely Americans in film schools and film festivals (after all, that was my world at the time of making the film). I also needed that shorthand to build tension. Namely: The Americans are launching today. There’s no time. We’re in crisis mode.

As I’ve developed this project, the point of view has shifted largely to the characters in the piece. In the feature film, without the need for shorthand, we definitely plant the gaze solidly in Zambia. It’s what’s exciting me as I go. I like to do detective work, I like to mine psychologies. And when your access point is the image, there’s a lot of mystery involved!

What went into your decision to cast yourself in your film? It made it such a personal piece, centering the space narrative on this woman’s internal point of view (the victory and joy and sadness and wonder...)

I think it lends the piece a performative quality and an intimacy that is hard to dismiss. The film posits a parallel universe, one that directly comments on the political condition of all Palestinians. In a way, the film is not trying to run away from reality in Palestine, but rather tries to find a different angle by which to address the same topic. There is a strong autobiographical note in the film and a personal need to understand artistic agency. I was born in Jerusalem, but like much of Palestinian history and culture, evidence of this is slowly being erased from the face of the earth. I cannot access Jerusalem now and only memories of it remain, making reality as surreal as the universes I create in my work. Palestinians can follow their dreams to the edges of the universe, but the flags they plant and the territories they claim will feel like defeats if there is no response from Jerusalem.

I was quite fascinated by your central character. How did you go about choosing the character and did you have a very clear idea from the beginning about the image you wanted to project with the main actor?

The main character, Matha, has albinism. This was a creative choice, not historically accurate. It’s one of those images that came instinctively, as the sort of “origin image” of the film: this “daughter of the moon” standing on a cliff of sand, gazing on at her unattainable home. This awesome image of outsiderhood & longing. Then it solidified itself in stories of people with albinism in East Africa (not Zambia, specifically) suffering persecution at the hands of witch doctors … this sense of, “is this mission just a glorified human sacrifice?” came forth.

But I knew I wasn’t making the film about the plight of people with albinism in Eastern Africa. Frankly, between Noaz Deshe’s White Shadow and Kim Nguyen’s War Witch, I’ve seen the subject matter handled well. And I think it’s a very foreign-minded to discuss what is exotically atrocious (“did you know they cut off their limbs?!” is not far from: “did you know they don’t have cutlery?!”). We almost expect that, if we have a heroine with albinism, the film will have to be about her albinism—much like when you see a black character on a soap opera and you just start gearing yourself up for the obligatory “who’s the father of the unborn baby?” plot line. I was psyched to have an albino star who is the only reason the mission is possible. The film is anchored in her bodily ability, and the limitations of human willpower.

Finally, serendipity played a part: I had been eyeing famous model Diandra Forrest from afar since I wrote the first draft. After all, you type in “young black woman with albinism” into google and she’s the only one to pop up. Then my cinematographer—the insanely talented Joshua James Richards, whose name I hope you are writing down—ran into her in a restaurant!

I thought the space costume you had was beautiful. It is a twist on a regular space suit. The helmet especially I think makes a statement. What were the reasoning behind your costume decisions and did you work with a costume designer?

I worked with the very talented Sarita Fellows, who works here in New York. We talked extensively about that in-between space. It was important for us to create a suit that existed within the paradigm of a suit, but kept the audience on this fine line of, “do they actually think she’s going to make it in that thing?” The space suit anchored the film’s tone: You’re in disbelief and yet you watch on.

It seemed to me that your work is sitting on the blurry line between utopia and dystopia. Is it something that you are consciously engaged with? I am curious because I felt that in your piece you approach the idea of space quite similarly to the way I contextualise the Middle East in a more universal setting concerned with progress and scientific advancement. The idea of reaching the moon is full of ambition and hope, yet your protagonist dies at the end of the film.

I’m very interested in the emotional moment that fold definitions/categories on top of each other. In this case, the desire for the near-impossible creates this positive feedback loop: The greater the distance between the subject and the object (of its desire), the greater the desire, and so on. When the desire-object is unattainable, things start to bend on top of themselves. We enter the sort of crisis moment that allows us to throw caution and disbelief to the wind to follow these Zambians in the desert rushing for their moonshot. You’re right in how quick a rush for this (utopic) space can create a certain dystopia: Is putting this teenager in a doomed rocket just a glorified human sacrifice?

We do have a very similar, jerry-rigged approach to space. And I think this is in keeping with a tradition of art made by various people of color (for lack of a better word) when considering space. I’m thinking Afro-futurism, Sun Ra, but also Twinkl and Kutlug Ataman’s A Journey To The Moon. We keep seeing a boundless imagination interacting with the economic reality/lack of access. How does this lack of access shift the “look” of space?

I think this look is a stylistic necessity for works that deal with heterotopia of illusion. In order to claim that something is not traditionally yours, you have to accentuate your “otherness.” In doing so, one is still buying into the clichés and terminology that you have been given. But that is how language works, and those are the first steps to dismantling those certain myths and constructs. Shifting the local discourse into the global one is very much a focus of these works. Also, claiming space is in itself an imperialist activity that does not sit comfortably with artists who traditionally occupy the oppressed or less privileged seat. I think this flipping of roles is what makes the works of the artists you mentioned much more poignant.

When will Palestine put a human on the moon? :)

It seems the moon is up for grabs for anyone who has a flag, but seeing as Palestinians currently don’t control the airspace above Palestine, I’m thinking a lunar shuttle might have to wait until we get a nation and full rights to the airspace :)

Speaking of symbols: I want to talk about the flag. I mentioned reclamation of land earlier. It was really emotionally exciting to see the Palestinian flag—so contested on earth—gloriously stuck into the moon’s surface. It’s probably the closest I’ve ever come to what Americans were possibly feeling on that day 1969! Talk a bit about this moment in your film. I think it emotionally goes beyond what it’s obviously referencing.

It is fascinating for me to hear you say that the moment of the Palestinian flag planting on the moon was emotionally exciting for you. I thought this sentiment would only be shared by Palestinians but I am very happy to hear that it transpires to the world beyond. But I guess because we work from a similar trajectory, empathy is easier to realise. Yes, this moment of the flag planting is an ambiguous one because it carries with it a feeling of achievement and great hope and technological prowess but at the same time it points at exile and the dream of Palestinian nationhood materialising in outer space. It reiterates the impossibility of the Palestinian predicament.

That moment, when the Americans planted the flag on the moon, is a poignant moment in Afronauts as well. I was interested in twisting the set of emotions we attach to that iconic moment. It’s a really sad moment in my film. In other words: I think it’s telling that the real Afronauts were setting off on this moon mission just after/around independence. In this era of decolonization, you still had two superpowers in a neocolonial race to plant a flag on the moon, to stake some sort of land out, to own it (with similar absurdity to the American father who last year planted a flag in Bir Tawil, between Egypt and Sudan, to stake out land and make his daughter a princess!)

Did you shoot the film in the US or somewhere else?

I shot the film on a beach in Sea Bright, NJ. Hurricane Sandy had just passed, and it had decimated this beach. So they’d brought heaps—hills—of sand over to flatten down and reclaim the beach. In that in-between moment (you can tell I like in-between moments), if you framed it just right, it became a vast desert.

I’m happy you brought up location, because I wanted to point out that both our moonscapes are ripping at the seams. The special effects are visible. I love these spaces that are visibly cracking open. I think this is ultimately what it means for a Palestinian or a Ghanaian to enter this clean, closed, bucolic idea of space. Constantly cracking it open to reveal that it lives up in our heads, really (in a sort of epistemological/metaphysical way because so few of us have experienced space), but also with the license to play with it and revel in it. Because who owns the moon? We all own the moon.