I don’t have a novel in me, but a novel has me in it. Although I consider myself a writer, I’ve never seriously considered writing The Great American Novel. Sometime in college, I set a more modest goal of appearing as a character in someone else’s work. Like Paul Wolfowitz, who appears in thinly disguised form in Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein, I just wanted a cameo that would grant me literary immortality. Is that so much to ask?

That immortality came mere months after I graduated from college, courtesy of one Megan McCafferty. Now McCafferty is no Bellow (and, thank goodness, I’m no Wolfowitz), but she is a popular author of what my sister and girlfriend assure me is high quality young adult chick lit. Her books follow the exploits of Jessica Darling, a bright and angsty young woman who is presumably a stand-in for McCafferty. The series began in high school with 2001’s Sloppy Firsts and continued through Second Helpings, Charmed Thirds, and the salaciously titled Fourth Comings, which is where I make my debut. Right there on page 24, McCafferty writes:

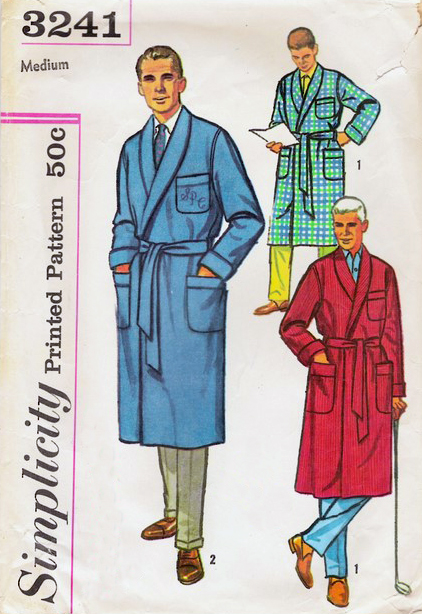

Columbia is in New York City, a place that isn’t exactly lacking in distinct characters. While I was there, a guy known as Bathrobe Boy gained notoriety simply because he couldn’t be bothered getting dressed for class.

Rough stuff, but accurate. Well, except for the part about McCafferty being there-- while I can’t speak for her fictional counterpart, McCafferty herself graduated Columbia in 1995, a full eleven years before me. When I emailed her to confirm that I was the inspiration for this passage, she wrote back:

Dave,

Well, I'm proud to play even a small part in spreading your infamy.

I can't exactly remember when I first read about you, though it probably was when I was researching my last book (Charmed Thirds--set mostly at Columbia) in 2005. I read several issues of various CC publications, and I must have seen that article you wrote in addition to other commentaries, posts on the bwog, etc.

By the way, I'm doing a reading/signing at the Borders @ Columbus Circle on September 6th. Show up in your bathrobe and it can be like, your first celebrity appearance...

Tell [redacted] I said hello. And thank your sister for me as well.

Best,

Megan

I never did go to that signing, and indeed my life has been one of complacency and mediocrity ever since. But I’ve always cherished this email. McCafferty was referring to an article I’d written for Columbia’s student magazine, The Blue and White, early in my senior year. That article, which unfortunately is not archived online, in turn referred to my freshman year habit of strolling around campus in my blue Gap bathrobe.

Why did I do that? I suppose McCafferty was right to characterize me as lazy. Lazy in two senses, really: the obvious sense of not feeling like getting dressed, and the more abstract sense of wanting to rebel without doing anything authentically rebellious. I wore my bathrobe to the library, the student center, the dining hall, and a Russian class. I generally wore boxers below it, and in the case of the Russian class, I believe I was fully clothed. Lots of people took notice, but I only ever got kicked out of a building on one occasion.

Wearing a bathrobe outside my dorm might have felt liberating in theory, but it was very constraining in practice. As I’d walk upstairs to check my mail at Columbia’s Panopticon-like student center, I’d hold my legs tightly together. I now recognize this as one of the more feminizing experiences of my life. I normally have the privilege to walk about unnoticed, but in wearing a bathrobe, I was inviting the campus to study me and judge me, and I was becoming more self-conscious even as I attempted to seem less so.

I should note that I’m... hirsute... and wearing a bathrobe made this obvious to all. Body hair, even on males, is something lots of people are uncomfortable with. While I regard this discomfort as invalid and borderline racist, I still felt like my body was more offensive to passersby than someone else’s body might have been. If I were mostly hairless (and, let’s say, blond and pale), wearing a bathrobe might have come off as adorable. Instead, it projected sleaze, which I promise was not my intent.

I did this just a handful of times as a freshman, and I might never have thought about it again if I hadn’t been traveling in Europe the summer before senior year. My friend and I had just stepped out of the famous Cafe Hawelka in Vienna, and we heard a girl call out across a crowded plaza, “Oh my god, it’s the Bathrobe Boy!” The girl in question wasn’t anyone I recognized, but she and her companion were fellow Columbia students who apparently recognized me.

When I got back to New York in the fall, I started writing for a number of campus publications, and in a desperate bid for a pitch, I recalled this incident. I wondered how many people remembered my bathrobe days, so I decided to revisit all my freshman haunts clad in the same blue robe, then to write a sort of parody of a how-I’ve-changed-since-freshman-year column.

To my surprise, someone who now has a legitimate media job approved this pitch, and to my much greater surprise, it was a hit. More than a few people remembered my robe, and it also helped me start conversations with younger students who’d missed the original Bathrobe Boy. One of these students was Atossa Abrahamian, who went on to become my good friend and another legitimate media figure. Many other students came to know and nurture the legend, and my act of literary self-creation achieved unanticipated heights when McCafferty discovered the story and shared it with a sizable number of teenage girls.

A lot of people who were in high school when I first wore the bathrobe seemed to think this had been a serious phenomenon, when the truth is that I had a very low profile on campus until I was a senior. In writing down the exploits of Bathrobe Boy, I was attempting to turn myself into an icon based on flimsy source material. It still amuses me how well this worked, and it gave me a lasting appreciation for how easily the media can hype an anecdote into a trend piece. Think about all those New York Times pieces about “The Way We Live Today” that are really just about the way some editor’s friend’s kid spent their vacation. When I presented my bathrobe-wearing habit as an actual story, as I’m doing again right now, I learned that bullshit works because lots of people enjoy being bullshitted. This is one of the more salient lessons of a liberal arts education.

A decade has passed since I first put on that bathrobe. The softness is gone, the edges are frayed, and my gut has nearly outgrown the capacity of the belt. I wear it sometimes, but only in the circumstances one normally would. I avoid cheap stunts, and I’ve developed some minimal respect for other people. While a bathrobe may be comfortable to wear, the appeal of flaunting my immaturity like a low-rent Hugh Hefner has diminished sharply. My youth and my robe are not eternal, I’ve learned. But with any luck, my mention in a young adult novel will be.