If male artist Chris Burden didn't exist, the New Museum would have to invent him

Two of Chris Burden’s sculptures adorn the stacked white boxes of the New Museum façade. Two Small Skyscrapers (Quasi Legal Skyscrapers) (2003/2013) sprouts up from the roof, a sepulchral reminder of the fallen World Trade Center towers. Beneath it is 2005’s Ghost Ship, a crewless, computer-navigated two-ton vessel repurposed as an epitaph for Hurricane Sandy. “Extreme Measures” marks Burden’s first New York museum exhibition, and his first U.S. survey in over 25 years. Best known for his ritualistically violent, body-based performances of the 1970s, Burden is a suitably “edgy” survey subject for an institution that prides itself on ungovernability. But behind the New Museum’s fig leaf of post-Sandy post-postmodern lies the time-honored art-historical project of male genius production.

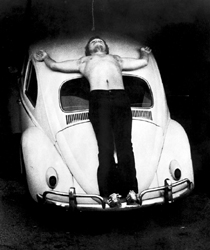

Chris Burden Trans-fixed (1974)

The New Museum survey arrives amidst a surge of institutional interest post-war art of Southern California — a trend manifest in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s sweeping Pacific Standard Time initiative, the inclusion of finish-fetish practitioners John McCracken and Craig Kauffman in MoMA’s minimalism gallery, and a spate of 2013 New York museum exhibitions devoted to Los Angeles-based artists, including James Turrell at the Guggenheim, Ken Price at the Metropolitan Museum, Llyn Foulkes at the New Museum, and Mike Kelley at MoMA PS1. “Extreme Measures” also synchs with the institutional vogue and popular mania for dematerialized performance-based art, evidenced by the foundation of Performa — New York’s first performance biennial — in 2004, the cult of celebrity surrounding Marina Abramovi?’s 2010 MoMA retrospective, the international scandal surrounding anarcha-feminist performance collective Pussy Riot, and the recent epiphenomena of celebrities reframing their activities as “performance art.”

“Extreme Measures” struggles to fuse two disparate halves of a career through the nebulous themes of radicality, polyvalence, and “an omnipresent fixation with the boundaries of power.” Burden’s art, pronounces curator Lisa Phillips in her catalog essay, “lives in a world of double binds and indeterminate realities: beyond simple truths and valences, binary rules and protocols—a world where danger, poetry, and absurdity collide, and struggles around power and control are ever-present.” The New Museum’s half-hearted attempt to rescue Burden from the myth of the artist-rebel results in a bizarre suppression of his canonical performance works in the exhibition layout. Even as the title of the exhibition anxiously reaffirms his unbroken bad-boy spirit, documentation of Burden’s “greatest hits” is archived in four loose-leaf binders on the museum’s fifth floor, while the vast majority of the institution’s square footage is consecrated to elephantine installations of his later, object-oriented production.

The textbook narrative of 20th century art history — girded by a logic of Oedipal rebellions and dialectical progress — tends to reduce an artist’s career to one or two “defining” works. New York Times critic Roberta Smith applauds the New Museum for “liberate[ing]… Mr. Burden from the clutches of history, expanding and rebalancing our understanding of his art.” But while the one-man survey helps to uncover the B-sides and deep cuts of an artist’s career, art historians Griselda Pollock and Linda Nochlin caution that this treatment reproduces gendered notions of artistic genius. In her groundbreaking 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists,” Nochlin implicates the monograph as a normative tool of masculinist canon-production. “Behind…the art-historical monograph,” she writes, “which accepts the notion of the great artist as primary, and the social and institutional structures within which he lived and worked as mere secondary ‘influences’ or ‘background’ — lurks the golden-nugget theory of genius and the free-enterprise conception of individual achievement.”

On the fifth floor, “Documentation of Selected Works: 1971-1974” — a 35-minute video montage of 11 of Burden’s performances — plays on a loop next to the bathrooms. These brief clips, played at a regrettably low volume, depict Burden subjecting himself to varying degrees of psychic discomfort and bodily harm: he gets shot in the arm (Shoot) narrowly avoids setting himself on fire (Icarus, 1973, and Fire Roll, 1973), flirts with electrocution (220), drowns himself by “inhaling water” (Velvet Water, 1974), stays in bed for 22 days (Bed Piece, 1972), maroons himself on a remote beach (B.C. Mexico, 1973), impersonates a cadaver in the middle of a Los Angeles thoroughfare (Deadman, 1972), is used as a human pincushion (Back to You, 1974), and cuts himself with broken glass (Through the Night Softly, 1973). The latter performance became the source material for TV AD. Purchasing a 10-second ad spot, Burden aired the clip of himself wiggling worm-like through broken glass, hands behind his back, to a unsuspecting and captive audience of 250,000 people. In the exhibition, we see it as it aired: jarringly sandwiched between commercials for '70s soft rock and bar soap, an unnerving intervention in the mundane programming of late-night cable.

Photographs and texts relating to 46 of Burden’s performances executed from 1971 to 1977 are filed in loose-leaf binders affixed to desks. This academic, deliberately anti-spectacular exhibition format resists a recent trend in performance art display, which — as performance art historian Amelia Jones notes in her 2011 article, “The Artist Is Present: Artistic Re-enactments and the Impossibility of Presence” — privileges the putatively revitalizing strategies of reenactment and homage over more conventional methods of photographic and textual documentation. “The massive resurgence of interest in performance art and its histories over the past five years has increasingly been worked through in relation to some variation on a newly developed re-enactment format,” Jones observes, citing Allan Kaprow’s 2008 MOCA retrospective and Marina Abramovi?’s 2007 Guggenheim and 2010 MoMA shows. Tellingly, Burden purportedly refused Abramovic’s request to reenact Trans-fixed for the Guggenheim’s “Five Easy Pieces” show. In its decidedly low-key presentation of Burden’s performances, “Extreme Measures” resists the emotional melodrama of the “Artist Is Present” school of performance art curation, with its insistence on the unmediated authenticity of the live human body. This more conventional, image-oriented strategy, however, needn’t mean the partial erasure of Burden’s early work. While his iconic photographs and explanatory texts could have been hung on the walls alongside his sculptures and installations, this significant body of work is instead demoted to the status of ephemera. The quietist mode of exhibition of these controversial performances can’t compete with the bellicose pyrotechnics of Burden’s later work.

If the top floor serves to simultaneously sustain and contain the myth of Burden-the-rebel, the fourth floor — with its attention to “the physical capacity of materials” – paints him in romantic hues as a virile wrestler with the sublime forces of nature. Here, we behold Burden’s first major post-performance object, The Big Wheel (1979), a gargantuan kinetic sculpture consisting of a three-ton cast-iron flywheel affixed to a 1968 Benelli 250cc motorcycle. This turbo-charged update of the Duchampian readymade squares off against “Porsche with Meteorite” (2013), a humongous teeter-totter that balances a vintage yellow convertible against a 390-pound iron space rock. In keeping with the theme of gravitational inevitably and material heft, video documentation from Beam Drop (1984, 2008, 2009), plays in a corner. Burden has executed “Beam Drop” on three occasions (in Lewiston, New York in 1984, Inhotim, Brazil in 2008, and in Antwerp in 2009) by dropping 60 large steel beams into a pit of wet cement from a height of over 100 feet, creating a monolithic abstract sculpture.

The third floor, which testifies to Burden’s engineering prowess, features two fully operational reproductions of a 17th century cannon (Pair of Naumar Mortars, 2013) alongside three of Burden’s model bridges: the stout, chalky-white Three Arch Dry Stack Bridge, 1?4 Scale (2013), the spindly, cantilevered Triple 21 Foot Truss Bridge (2013), and elegant, triple-arched Mexican Bridge (1998). The latter two were constructed from pieces modeled after 100-year-old Erector set parts. As curator Fred Hoffman explains in his essay for Burden’s 2007 monograph, the Meccano-erector set was invented at the turn of the 20th century “for the purpose of enabling children to become acquainted firsthand with the technologies then driving western industrialization.” The wall text claims that Burden, as the son of an engineer, is keenly aware “of the destructive and ego-driven tendencies latent in engineering pursuits.” While tantalizingly vague, this idea is hardly evident in Burden’s bridge sculptures, which, to the contrary, seem to suggest post-Fordist nostalgia for American industry and the forgotten boyhood pursuits of tinkering, model-making, and brick and mortar construction.

The man-child aesthetics of Burden’s later work is most evident in A Tale of Two Cities (1981), a breathtaking 1,000-square-foot sand-based diorama that dominates the second floor. Situated in a toyland topography of miniature mountain ranges, house plant jungles, and city walls constructed out of real bullets, the titular two cities make war with an impressive arsenal of over 5,000 toy tanks, airplanes, guns, and tiny action figures. In her catalog essay, curator Johanna Burton incisively observes that “Two Cities,” “for all its attempts at illustrating something of the ethos of war…simultaneously exudes the über-fetish quality of a child’s fantasy, here realized, not in the family game room, but in the museum.” It is not, as Roberta Smith would have it, a monument of peacenik protest, but “an acknowledgment of the horrors of war and an obscene, hyperbolic abstraction of them.” Survivalist fantasies are indulged in the formally underwhelming “Beehive Bunker” (2006), a pyramid-shaped DIY fortification composed of stacked bricks of pre-mixed concrete wrapped in red and yellow paper.

To read gender in Burden’s work is not to argue that any art that deals with the conventionally masculine subject matter should be omitted from art history, removed from museums, or essentialized in Manichean terms. In fact, the New Museum neuters and universalizes the gendered aspects of Burden’s work — what Robert Storr has sympathetically called its “boys with their toys” character. In its gender-blindness, the exhibition codifies the great artist as normatively male, rather than comprehending, as Pollock advocated, “conflicting masculine desires, liberated from their theological encasement in the idealized image of the canonical artist.”

Given the troubling interplay between physical vulnerability and male-coded aggression in Burden’s performances, it’s regrettable that Match Piece (1972) and TV Hijack (1972) are buried under a gravestone of stationary. In the latter work, Burden assaults a female talk show host during a televised interview. Burden’s textual account of the performance is typically terse “Holding a knife at her throat, I threatened her life if the station stopped live transmission. I told her that I had planned to make her perform obscene acts.” In Match Piece — performed in a gallery in front of an audience — Burden catapulted lit matches at his then-wife, Barbara Burden, who was lying 15 feet away naked and prostrate. Again, sexually charged violence is rendered in a language of administrative objectivity: “Some of the rockets landed on her body leaving small burns, others landed in the audience.”

Phillips calls Burden’s effigy of the Twin Towers “eerie reminders of lost souls and ever-present threats.” But do these sculptures really serve to memorialize and remember? Or is their purpose to lend a patina of moral seriousness to the exhibition of tremendous art spectacles that — while paying lip service to some vague “critique of power” — embody the very authority (and phallocentrism) the curators position Burden against as a figure of romantic rebellion? The artist’s repertoire of monster trucks, boulders, and toy submarines — rendered in the international style of large-scale, conceptually-oriented sculpture and labeled with the artist’s empiricist, mansplaining texts— are neutered, neutralized, and inoculated against feminist critiques when ensconced in the New Museum’s pristine post-minimalist architecture, and filtered through its ideology of nominally progressive, haute-hipster consensus.

Itself caught in one of Phillips’s “double-binds,” Extreme Measures attempts to memorialize the anti-market, anti-object politics of Burden’s dematerialized artwork, while — in the same breath and institutional setting — celebrating the proto-Hirstian Tower of Power (1985): a ziggurat composed of 100 gold bricks. The monolithic bombast of works like Big Wheel and One Ton Truck have less to do with “omnipresent fixation with the boundaries of power” than with a current vogue for neo-baroque art spectacles that bulldoze over critical engagement, producing the ideal viewer as slack-jawed oglers. Human scale is sacrificed to a cult of gigantism and spatial sublimity. Taking pains to escape the myth of Burden as an overgrown enfant terrible, “Extreme Measures” produces secondary, less intriguing ones: Burden as technocrat, apostate, and authorial rubber stamp on supersized contemporary art baubles.