In an exclusive conversation, surveillance scholar Simone Browne and artist Zach Blas critique various forms of “control diagrams” and imagine a new commons in the space between the Internet’s network nodes.

SIMONE BROWNE. The soundtrack for artist Zach Blas's “Contra-Internet Inversion Practice #3: Modeling Paranodal Space” comes from the corresponding title track to Joe Meek and The Blue Men’s 1960 concept album “I Hear a New World.” The album, Meek wrote, is a deliberately “strange record” meant to conjure up rockets, science fiction, moon landings before the first moon landing, as well as “whatever could be up there in outer space.”

Zach, there's a lot that you are questioning and putting forward in this piece: The disappearance of the Internet, the killability of the Internet, Paul Preciado’s queer concept of constrasexuality, dildotectronics, and a commons to come.

Tell me, Zach, what motivations went into creating the project? Why Meek and The Blue Men’s “I Hear a New World,” and how will the contra-Internet get us to the commons to come?

ZACH BLAS. Contra-Internet is a series of artworks and writings that I've been working on since 2014. Spanning video, sculpture, installation, and performance, the project confronts the Internet as an instrument for control, state oppression, and accelerated capitalism. Over the next several months, I will be focusing on a video centerpiece, which turns to alternative Internet infrastructures that activists are building around the world. In September 2017, Contra-Internet will premiere as a solo exhibition at Gasworks in London. That said, I began the Contra-Internet project with two questions to use as a basis for research and experimentation:

1) When and how did the Internet transition from a site of immense political potentiality to a premiere arena of control, surveillance, and hegemony?

2) Why is it so difficult to conceive of an alternative or outside to the Internet today?

It seems, on the one hand, that the Internet operates as a kind of totalized condition, constricting what is possible for communicating, gathering, and being together. Popular concepts like “post-Internet” propagate this sentiment: there can no longer be an outside to the Internet when it has already seeped into the very material fabric of contemporary existence. Prophecies of the Internet of things to come promise to secure this understanding of the Internet, as the world itself and the Internet become more and more indistinguishable. That said, it strikes me as queer to desire to fracture this Internet totality, and in fact, on the other hand, many people around the world are practically doing just that, by building infrastructural alternatives to the Internet. These include certain tools that activists, hackers, and artists around the world are building to avoid control and surveillance. Mesh-networking is a powerful example to consider, as it is a networking technology that can function autonomously with no reliance on “the Internet,” and has been used to constitute political alternatives in cities such as Detroit, New York, and Hong Kong.

A working definition of contra-Internet is the refusal of Internet totality, but this is not a simple outright refusal. Rather, it is a refusal of naturalizations, hegemonies, and normalizations of the Internet that have contributed to its transformation into a locus of policing and control. Supplementing this, contra-Internet is also the search for and constitution of Internet alternatives. I consider the examples of alternative infrastructure outlined above as crucial to the contra-Internet because they reveal that social movements no longer necessarily see the Internet as a political horizon--it is, rather, about finding something else. This is where the commons comes in for me, as a collective and open project of thinking, imagining, and building something other than “the Internet.” From an artistic perspective, I would like Contra-Internet to give a particularly queer consistency to this activity, and this must happen not only by documenting Internet alternatives but also by imagining beyond the network form itself.

I have developed this idea through a reworking of Paul Preciado’s theory of the contrasexual, which takes a similar aim at sexuality. This move from the contrasexual to the contra-Internet could be described as “utopian plagiarism,” which Critical Art Ensemble theorized about in the early 1990s (and which I learned from one of the most important art mentors in my life, Ricardo Dominguez). At the beginnings of a recombinant Internet culture, Critical Art Ensemble imagined a networked mode of sharing and re-writings ideas--of remixing words and images to unearth alternate and minor meanings. This is exactly what the group did with one of their most well known concepts--electronic civil disobedience, created by taking Thoreau’s theory of civil disobedience and making it electronic. That said, it’s not that contra-Internet is a radical break with the contrasexual; rather, it extends that concept and (hopefully) makes something new comprehensible. While Preciado has been a starting point, I’ve been quite interested in developing the broader conceptual framework for Contra-Internet out of queer, feminist, and minoritarian thinkers and artists, be it J. K. Gibson-Graham’s post capitalist politics, Le Tigre’s “Get Off the Internet,” or Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s undercommons. I believe their teachings in seeking alternatives to domination and control are of the utmost importance here.

This brings me to the video you mentioned. I am in the process of making a series of videos for the Contra-Internet project that take place within the technical, material, and visual confines of the computer--namely, the computer I use, a Mac laptop. These videos are kind of like performances, and they attempt to invert the logics, visualities, and software environments that condition and delimit the discursive, practical, and creative possibilities of the computer (again, this idea of inversion comes from Preciado’s “inversion practices” in his Manifiesto Contrasexual). The computer is a starting point for writing, imagining, and experimenting, so it felt crucial to literally start here. In the Contra-Internet Inversion Practice #3, I am exploring what going beyond the network form looks like.

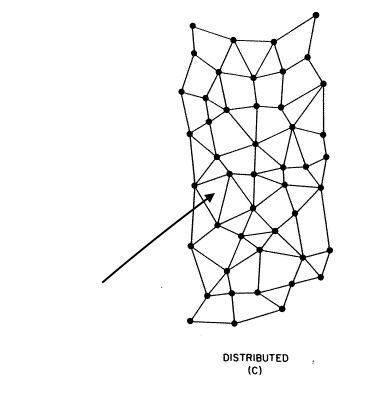

To do this, I import a well-known distributed network diagram--the kind of network diagram often used to describe the Internet--into three-dimensional modeling software, and then I peel away and discard the network diagram, in order to liberate the space bound to this configuration. Several ideas led me to this point: I have been very taken by Preciado’s figuring of the dildo. For Preciado, the dildo is a diagrammatic form that can practically guide us to contrasexuality (the dildo is not a phallus or anything patriarchal for Preciado). My question here is what might the dildotectonics of the Internet be? What I mean by this is: if the dildo is an adequate form to unleash contrasexuality, what form might this be for the Internet? Certainly not the network form.

In a recent conversation with digital humanities scholar David Berry, media theorist Alexander Galloway proposes the idea of reticular pessimism, a criticism of the network as a dominant model for interpreting reality. Galloway suggests that today the network, through its dominance and ubiquity, forecloses the utopian. The reticular pessimist is unable to grasp the world and its potentialities as something other than a network. As an artist, this is a provocative claim to consider, as it evokes the beyond-or-other-than the network as something needed but not yet fully known. For me, this is where imagination must begin. Network theorist Ulises Ali Mejias offers the second step to this disavowal of the network form through his concept of the paranode, which he explains as the space that networks leave out or exclude. I have a hunch that the paranodal is one way to conceptualize the dildotectonics of the Internet. I am attracted to the concept of the paranode because it calls forth at least two militancies: the practical work of building infrastructural alternatives (which are often still network alternatives), and the intellectual or artistic task of making comprehensible and imaginable that which is beyond the network form.

So finally, the 1960 song “I Hear a New World” by Joe Meek, which plays throughout Practice #3. It has always struck me as inextricably queer, before I even knew anything about Meek. Of course, there’s his biography: a gifted sound engineer and closeted gay man whose life ended in suicide and murder (he lived in England during a time when homosexuality was illegal, and he also killed the proprietor of his flat before he shot himself). The song--and the entire album it appears on--is an outer space fantasy, one that projects outer space, it can be inferred, as outside the confines of Meek’s difficult present on Earth. The music is futuristic, a bit kitschy, haunting, and filled with desire. It’s the anticipation and longing that really gets me in this song--the hearing a new world but not yet there, sensing something to come and not fully knowing what that might be--being attuned to another possibility. When the paranodal space is freed from the distributed network diagram, all of these sentiments and feelings of Meek’s music really coming rushing in for me. It is Meek’s haunting of the paranodal space that makes me hear a new (queer) world.

SIMONE BROWNE. I also want to talk about a different project of yours, Face Cages, as another moment of this queer consistency. But first a primer of sorts on biometric technology, which we can think of as code or a set of instructions employed to render the body, living or otherwise, as machine-readable information.

This information--abstracted from parts, pieces, and performances of the human body--is then put to work in the service of consumer products, military applications, gaming, identification documents, and a variety of other applications. Biometrics, as the computational representation of the physical, behavioral and, more recently, affective attributes of the human body, are of many types: the face, for example, and the variety of biometric modalities when it comes to measures of the human face, including retina scans, iris recognition, thermal face imaging that detects the supposedly unique emission of a face’s heat pattern, and the more commonly known facial recognition that measures the spacing between the eyes, nose bridge, and more.

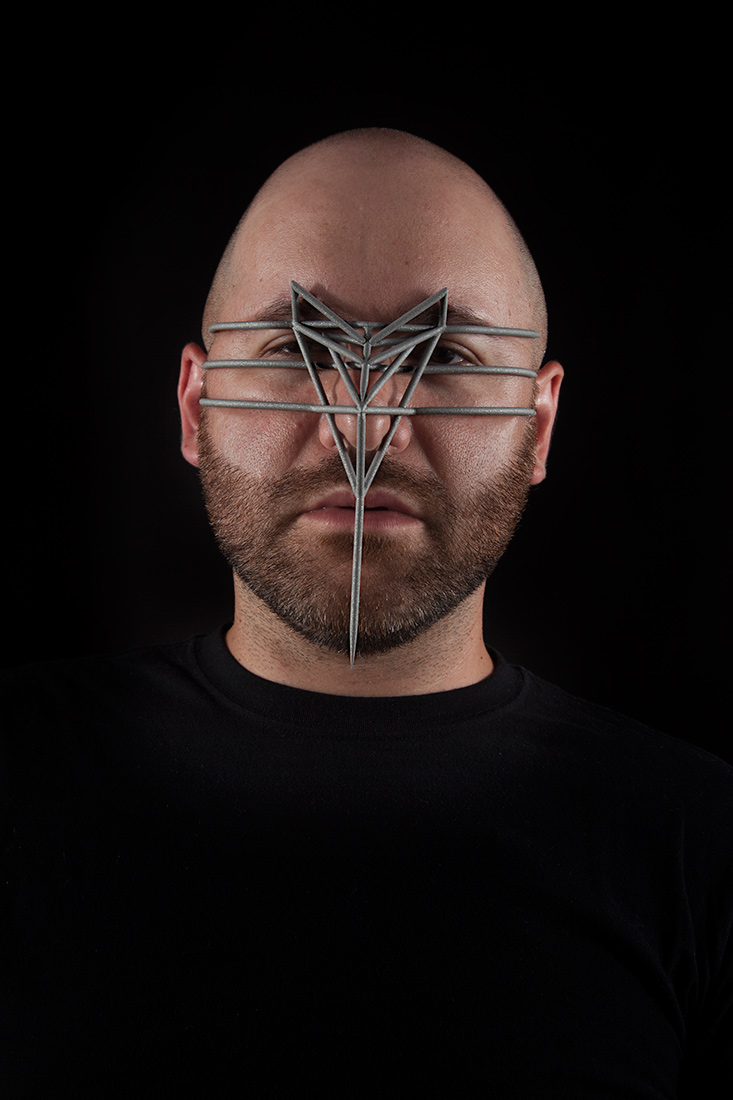

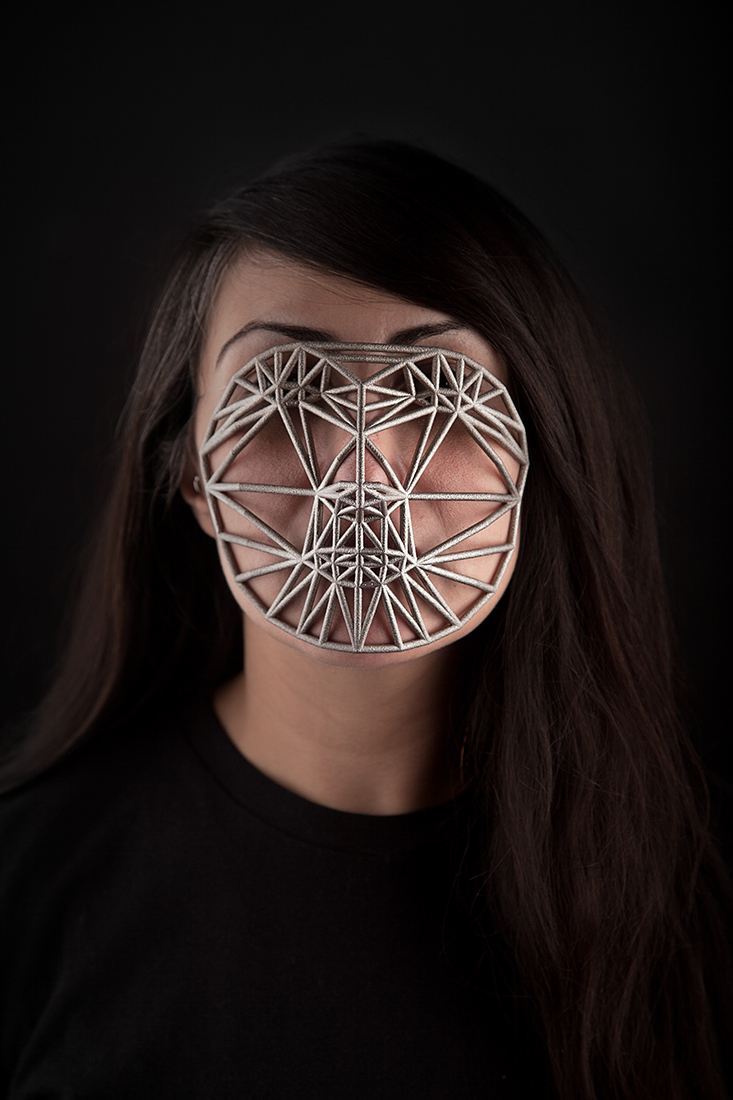

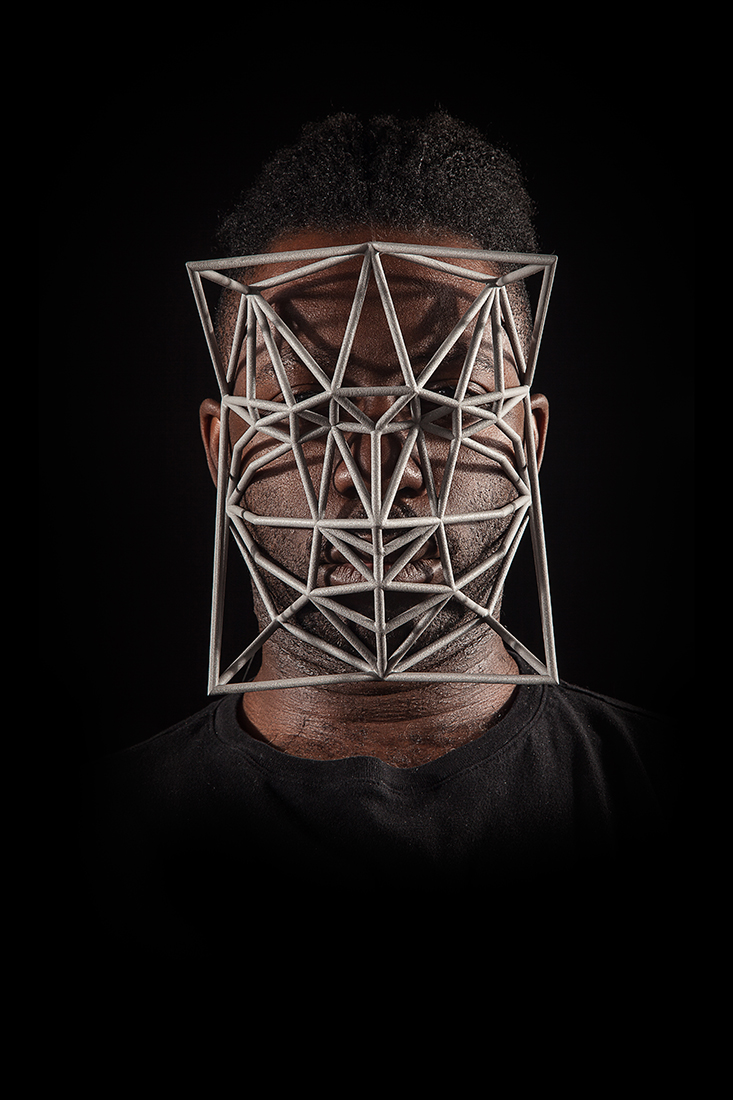

Your video installation Face Cages is the structure of the algorithm rendered as a three-dimensional metal cage. Face Cages makes it so that facial recognition can’t be reconciled with its use to ban, expel, and account for certain humans’ bodies at borders, in prisons, or on kill lists. I see the metal work of the cages and I think of iron masks, copper fastenings, and metal collars used to torture, gag, muzzle, and restrict enslaved people when it came to breathing, speaking, eating, or escape.

This was especially so when I watched the four Face Cages performance videos. The masks restricted their breathing so that it was labored. Each inhalation seemed tense. Each exhalation the same. You call this installation an endurance performance, and for me it brings to mind Frantz Fanon’s “combat breathing” that he writes about in A Dying Colonialism. The suffocating corporeal effect of colonization is one felt not only at the site of occupied territory, but experienced physiologically on the body as what Fanon names “occupied breathing.” It is respiration as unfreedom.

The endurance performance work of Face Cages is that of four queer artists: you, micha cárdenas, Elle Mehrmand and Paul Mpagi Sepuya. This makes the endurance work of Face Cages a form of combat breathing in an anti-queer and transantagonistic world, where biometric technologies enable the growth of mass surveillance and incarceration. How do you see Face Cages and your other projects that critique surveillance technologies as part of an anti-colonial queer politics? As undoing, in some way, enduring and ongoing settler-colonial structures?

ZACH BLAS. The central question of Face Cages is how to intensify and dramatize the violence of biometrics. I chose to pursue this through the ways in which biometrics abstracts bodies. This can technically (and I would argue politically) be defined as capture. I particularly focused on the landmark plotting technique of facial analysis that generates bright, colorful, and minimal geometries over the face, as a seemingly perfect calculation of its specificities. I call this a biometric diagram, and it appears as something primarily aesthetic. Yet, I wanted to make explicit that this diagram is not just an aesthetic abstraction of body parts but also a diagram of control. Thus, I think of the biometric diagram in a Foucauldian sense, as a mapping of power. While Foucault once described the panopticon as a major diagram of power in the 19th century, I think biometrics is one of today’s major control diagrams. As such, this mode of abstraction has an explicit and unavoidable collusion with global surveillance and the prison-industrial complex.

I decided to recast the biometric diagram as a face cage, which I developed from the writings of feminist communications scholar Shoshana Amielle Magnet, particularly her phrase “a cage of information.” Biometrics as a cage of information highlights two key points: 1) criminalization, as biometrics are first and foremost a technology of policing, and 2) disembodiment, because biometrics promotes a conception of identity that can be digitally extracted from the surface of the body. Alternately, embodiment, as media theorist Kate Hayles has argued, is not algorithmic.

In Face Cages, I took four biometric diagrams of faces and transformed them into metal cages. Metal intensifies, makes heavy, the physicality of biometric abstraction, but I also used metal to evoke aspects of policing, such as handcuffs and prison bars. I worked with three other artists that currently embody those persons most vulnerable to biometric scrutiny, in terms of ethnicity, gender, nationality, and race. I produced face cages based on our biometric data, and when worn, they were remarkably ill-fitting, causing pain and discomfort, even though these cages should sit perfectly on the surfaces of our faces, following biometric logic.

We wore our face cages in endurance performances for a video camera--the prompt being to wear it until you can’t bear it any longer. These performances aim to dramatize the struggle between embodiment and biometric capture, as algorithmic abstraction becomes hyperphysical, felt, violent, painful, and endured over time. Your reference to Fanon’s occupied breathing is important here, because I made Face Cages with the hope that it would expose the long histories of colonialism, oppression, and violence inherent to biometric technologies. Here, I am reminded of another concept I’m doing much work around these days, which is feminist science and technology studies scholar Donna Haraway’s “informatics of domination.” In her “A Cyborg Manifesto,” Haraway renames white capitalist patriarchy as the informatics of domination, “the scary new networks” that are united by “a common move--the translation of the world into a problem of coding.” I think one of the goals of recent queer, feminist, anti-racist, and anti-colonial work that addresses technologies like biometrics (in critical writing and the arts) is to demonstrate how this informatic coding impacts, violates, and destroys minoritarian lives.

Another way to explain how biometric capture dominates is through its attempt to obliterate opacity. For a number of years, I have been taken with opacity as an anti-biometric concept that is particularly sensitive to minoritarian lives--I am even currently writing a book titled Informatic Opacity. I have developed such an idea from the writings of Édouard Glissant, whose claim that we must “clamor for the right to opacity for everyone” could be a slogan for biometric times. Opacity, for Glissant, is a vast and robust conception; it is at once ethical, political, aesthetic, and even ontological. Glissant gives us multiple definitions and tendencies to consider: “Opaqueness is a positive value to be opposed to any pseudo-humanist attempt to reduce us to the scale of some universal model” (how can this not bring to mind biometrics?); “that which protects the Diverse we call opacity”; and he even states that opacity is the very aesthetics of the Other. Glissant also distinguishes opacity from difference, in that opacity exceeds the terrain of identity and identification.

With a concept like “informatic opacity,” I am interested in addressing how current struggles for opacity must confront both humans and machines. I explored what informatic opacity might look like in an earlier artwork titled Facial Weaponization Suite, in which I produced masks in public workshops based on the aggregated facial data of participants. The resultant masks--a kind of collectivization of the face in data--could not be detected by biometric facial recognition technologies as human faces. Of course, there are other theoretical ways to think about opacity today: queerness as a mode of escape, feminist imperceptibility, black fugitivity, or your own term “dark sousveillance” all come to mind.

SIMONE BROWNE. Yes, there is a part in Glissant’s “For Opacity” from his Poetics of Relation where he argues that Western thought’s pathological demand for understanding is underwritten by hierarchies and a “requirement of transparency.” He writes that “in order to understand and thus accept you, I have to measure your solidity with the ideal scale providing me with grounds to make comparisons and, perhaps, judgments, I have to reduce.” He says we must do away with “the scale.”

There’s another part of Poetics of Relation that I want to cite here, as a way to close. It comes from its beginnings, “The Open Boat.” In it, Glissant speaks of metal balls and chains gone green and what the slave ship left in its wake. Importantly, he reminds us of why we must stay with poetry, with that which expresses our freedoms. So I like that you mentioned earlier about being attuned to another possibility. I think that’s what Glissant left us with: the places, the means and the ways to start looking for other possibilities.

ZACH BLAS. Thanks for highlighting Glissant’s critique of scale, which, as you indicate, can also refer to measure, classification, and categorization. I am currently at work on a few new art projects that continue to expand upon the political implications of algorithmic measure in capture technologies and security apparatuses.

I have returned to biometrics after recently moving to the United Kingdom. Before arriving in London, I had to apply for a “Biometric Residence Permit,” which is the U.K.’s official title for a work visa, and as part of this process I was required to attend a “biometric enrolment” appointment where facial and fingerprint data is gathered. When I received the online notification to attend my biometrics appointment in New York City, I was struck by the following statement:

“This is either to submit documentation and/or to enable us to collect your biometrics, unless you are bio-exempt.”

Unless you are bio-exempt. What a fantastical, impossible category! If you look through more official literature on biometrics from the U.K. Home Office, you will come to understand that children and amputees with one or no fingers are bio-exempt, but so are diplomats. If you look more closely at this material, you will also notice that Home Office alternates between the term bio-exempt and the phrase “exempt from control.” I am finding my way towards a work titled bio-exempt, in which I aim to pull out all the term’s various meanings, such as biopolitical control: who has the legal right to be exempt from their embodied self and who has the right to remain unmarked, not indexed.

In a second work titled The Prison-House, I am reimagining Fredric Jameson’s conception of “the prison-house of language” as the prison-house of capture. I want to ask something like: If the architectural diagrams of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon broadly mapped power and discipline in a previous era, what might such architectural renderings and diagrams look like now? To do this, I am making a series of immersive installations that collapse secret interrogation rooms, torture chambers, and the world of machine vision into one another to dramatize a “prison-house” structure that is mobile, flexible, often invisible, and thoroughly informatic.

Lastly, and perhaps of a more utopian sentiment, I’m working on a video-essay and installation (and collective!) titled The Outside. The outside is an idea often evoked today by speculative realism, object-oriented ontology, and others focused on the nonhuman turn, united in their pursuit to get out of what philosopher Quentin Meillassoux describes as the correlationist trap, that is, understanding the world only through the human ability to grasp, know, and perceive it. The other side of correlationism, Meillassoux proclaims, is “the great outdoors.” Yet, there is a more minoritarian outside that has been operative and at work before the rise of these other intellectual endeavors, oriented towards undoing totalities, making alternatives, and combating domination. Consider “the black outdoors,” discussed by Fred Moten and Saidiya Hartman; the post-capitalist politics in J. K. Gibson-Graham’s writings, when they argue that there is an outside to capitalism; Donna Haraway’s insistence that “there might indeed be a feminist science”; or even George Michael’s sex-positive “Outside,” when he sings, “Let’s go outside.” This outside might return us to Glissant again--as a way of being outside of “the ideal scale,” which goes to your point Simone, about freedoms and relation.