In the current movement against white supremacy and the police we can see the beginnings of a new Black Arts Movement

Tell me something

what you think would happen if

everytime they kill a black boy

then we kill a cop

everytime they kill a black man

then we kill a cop

you think the accident rate would lower subsequently?

In 1978, June Jordan presaged the fire our time with her “Poem about Police Violence,” written after the NYPD choked Arthur Miller to death in Crown Heights (a lynching method that would later kill Anthony Baez in 1994 and Eric Garner in 2014). Her poem highlighted how the "diction of the powerful" can re-construe police brutality as "justifiable accidents", while community defense efforts are distortedly framed as resisting arrest and incitement to riot. Jordan’s question—how to settle scores, how to push the limits of freedom as an act of re-humanization—flows out of the long lineage of the Black Arts Movement, in which poetry and performance offer insurgent experimental space to test ideas that can be enacted, while social conflicts are absorbed into and shared across spoken words. Jordan and other radical artists called for retribution against police violence, revealed the dignity in rioting (reparations), and illuminated new directions for Black lives not just to matter, but to articulate the furthest horizons of liberation.

Chickens have once again come home to roost in New York City. Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, killed on December 20, then Andrew Dossi and Aliro Pellerano shot on January 5, are likely the first of more police officers who will be targeted for street retribution, and the NYPD’s longstanding policies of racial violence are squarely to blame. The NYPD’s “work” slowdown backfired amidst major fissures between Mayor de Blasio, Commissioner Bratton, City Councilmembers, and police officers, and Peter Liang's February 11 grand jury indictment for the murder of Akai Gurley signals an erosion of police impunity. This opens up a remarkable opportunity for community control, transformative justice, and other alternatives to policing to be undertaken. Meanwhile, recognition of queer Black women’s creation of the #BlackLivesMatter meme, defenses of rioting, and critical histories of policing circulate, as Black movement-centering films like Concerning Violence, Dear White People, Fruitvale Station, Selma, and The Throwaways begin to proliferate.

What can we learn from the Black Arts Movement, at its height during the last long period of urban rebellions in the 1960s and 70s? We can begin by assessing the direct link between poetics and street tactics manifested by Jordan and other writers like Amiri Baraka, who demanded in the 1966 poem “Black Art,” "we want ‘poems that kill.’ / Assassin poems, Poems that shoot / guns. Poems that wrestle cops into alleys / and take their weapons leaving them dead." In the 1967 poem “Black People!,” he urged readers to reclaim countless goods that an economic system had stolen from them across centuries: "All the stores will open if you will say the magic words… Up against the wall mother fucker this is a stick up!" At his packed community readings, people would shout these familiar lines with explosive delight. With the Black Arts Repertory Theater in Harlem and Spirit House Players in Newark, Baraka wrote and performed one-act plays like Arm Yourself or Harm Yourself infused with debates about how poor Black communities could confront police brutality.

Diane DiPrima, an Italian-American sister of the Black Arts Movement, dispatched “Revolutionary Letters” that enjoined uprising communities to store dry foods, water in bathtubs, salt and matches in case city officials shut off utilities. She launched these poems as direct action trainings for readers to anticipate and avoid tear gas, kettling, unfamiliar protest sites: "Everytime you pick the spot for a be-in / a demonstration, a march, a rally, you are choosing the ground / for a potential battle. / You are still calling the shots. / Pick your terrain with that in mind." David Henderson’s 1970 poem “Keep on Pushing,” also analyzed the geographies of urban warfare in the Summer of 1964’s Harlem Riots. Henderson warned of the crude mathematics of wide avenues that can swallow protest pickets, easily dismantle popular barricades, and muster five hundred cops in fifteen minutes, but he also suggests how, "For Harlem/ reinforcements come from the Bronx / just over the three-borough Bridge. / a shot a cry a rumor / can muster five hundred Negroes / from idle and strategic street corners / bars stoops hallways windows."

As today, so Black women half a century ago were among the most lucid movement leaders and artists, possessing a unique insight to speak and listen across multiple valences of oppression and resistance. In 1959, Black lesbian playwright Lorraine Hansberry measured how "the most oppressed group of any oppressed group will be its women, obviously"—therefore, those who are twice oppressed can become twice militant (or in the case of Hansberry, thrice militant). By 1970, Black novelist and filmmaker Toni Cade Bambara documented:

Black women have been forming work-study groups, discussion clubs, cooperative nurseries, cooperative businesses, consumer education groups, women’s workshops on the campuses, women’s caucuses within existing organizations, Afro-American women’s magazines… they have begun correspondence with sisters in Vietnam, Guatemala, Algeria, Ghana on the Liberation Struggle and the Woman, formed alliances on a Third World Women plank.

As these political formations widely flourished, Black Arts poetics also identified women of color’s holistic rebirths and reclaimed lineages, as Sonia Sanchez revealed in 1974, "come ride my birth, earth mother / tell me how i have become, became / this woman with razor blades between / her teeth. / sing me my history O earth mother / about tongues multiplying memories / about breaths contained in straw."

• • •

Call our present moment a Black Arts Boomerang. We have yet to close the gap between street actions and popular culture, personal and social liberations, but bridges are being built and traversed fast. Consider how, within the last few months, Lauryn Hill’s “Black Rage,” D’Angelo’s Black Messiah, J. Cole’s “Be Free,” Azealia Banks’ Twitter salvos on reparations and respectability politics, the new “Wizard of Watts” Adult Swim cartoon, and Kendrick Lamar’s “Untitled Track” Colbert performance have directly addressed our racial justice struggles. Lamar’s lyric, "we don’t die, we multiply!", was repeated at #BlackLivesMatter actions mere days after being televised. His earlier collaboration with Flying Lotus, “Never Catch Me,” embraces the fear of death, catalyzed into "that quantum jump and that fist pump and that bomb detonation." The song’s music video, released October 1, is a surprisingly jubilant homage to dead children resurrected that conjures up visions of Mike, Tamir, Yanira, VonDerrit, Cameron, Emmett, and many others returning home.

Claudia Rankine’s standout 2014 poetry collection Citizen: An American Lyric offers rhythmic meditations on Black people ensnared by police stop and frisks, co-workers, sports, cultures, each other, themselves. "Then flashes, a siren, a stretched-out roar—and you are not the guy and still you fit the description because there is only one guy who is always the guy fitting the description." Rankine details quiet acts of solidarity with Black men—sitting alongside one on the subway whose proximity others refuse, cradling telephone silence with another who is stunned from too much to say—as she traces the sutures of exhausted rage from daily acts of racism, and questions why only Black writers are responsible for chronicling anti-Blackness. The collection presciently concludes, "I can hear the even breathing that creates passages to dreams."

Meanwhile, our streets have swelled with direct action poetics, polyphonic melodies, counter-power maps, images of alchemical resistance. Black Arts cultural critic Larry Neal’s words in 1970—"A realistic movement among the black arts community should be about the extension of the remembered and a resurrection of the unremembered"—resound today. During the recent Millions March NYC, Eric Garner’s stare was held aloft by a surging body of thousands, as Mike Brown’s walk down the middle of the street was reenacted by entire families. "Hands up, don’t shoot" became "Fists up, fight back." Marches stretched up to Harlem proclaiming "No struggle, no progress" and "By any means necessary" on Frederick Douglass and Malcolm X Boulevards. Final words were transformed into incantations of endurance: I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.

Lyrical eulogies fashioned on the spot carried the names of the dead: "Turn up, don’t turn down: we do this for Mike Brown. Push back, now push harder: we do this for Eric Garner. Hands up to the sky: we do this for Akai. This is why we’re here: justice for Tamir." Remixes, layered one after another, wove improvisations and pop references: "No cop zone, No cop zone! They know better, they know better!" (after Rae Sremmurd’s “No Flex Zone”)... "Turn down for what?" (DJ Snake and Lil Jon)... "All I wanna say is they don’t really care about us!" (Michael Jackson). Humor ridiculed over-inflated police: "Why you dressed in riot gear? I don’t see no riot here." Double dutch-swarms cleverly shut down intersections: "They think it’s a game. They think it’s a joke." New strategies were tested on the tongues of those who will enact them: "Community control, it’s our demand. Can we do it? Yes we can!"

Interventionist theater played out on bridges, highways, squares, parks, stations, commerce events, as helicopters crisscrossed the sky and cop cars trailed behind crowds like sideways christmas lights. Brooklyn Bridge, Manhattan Bridge, Triborough, Verrazano, FDR, West Side Highway, Foley Square, Times Square, Union Square, Washington Square, Bryant Park, Columbus Circle, Grand Central Station, Macy’s Parade, Rockefeller Tree Lighting, Saks Fifth Avenue—these major city arteries clogged with the thick boil of intergenerational blood. Most recently, #BlackBrunch’s 4.5 minute Sunday interruptions in posh restaurants lay realities of bullet-riddled Black lives on the tables of white supremacist insularity, whose furious backlash offers the most damning evidence of the action’s relevance. These wildcat tactics inherited from anticolonial liberation movements practice the “war of the flea”—urban guerrilla methods of swarm-strike-fade-repeat to disrupt/transform multiple places at once, while avoiding “hard lock” occupations that can result in mass arrests that would slow down mobilizations of such confident character.

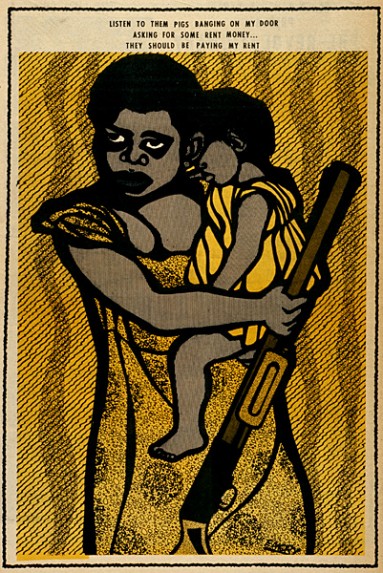

These Black Arts legacies from half a century ago can also help us articulate today how freedoms of artistic expression are neither synonymous nor compatible with maintaining systems of oppression, but can rather work to overturn caricatures and the ideologies that shape them. For instance, Black Panther artist Emory Douglas’s work was suffused with satire, violence, and critiques of religion, but his creative compass was antithetical to the likes of Charlie Hebdo cartoons. Although the 12 French artists should not have been murdered, their pens flowed from the ideological wells of European and United States neocolonial that are inflicted upon the rest of the world. For the Western world to consider the recent attacks a complete shock recalls a dangerous naivete that Jean-Paul Sartre warned about in 1961: It is the moment of the boomerang; it is the third phase of violence; it comes back on us, it strikes us, and we do not realize any more than we did the other times that it’s we that have launched it. It’s indeed telling of the dominant moral calculus how little mainstream U.S. media covered the January 3 Boko Haram massacre of up to 2,000 Nigerians, the January 6 Colorado Springs NAACP office bombing, and the February 10 Chapel Hill hate-killings of three Muslims, in contrast to the Paris shootings.

In this rare moment of mass memes, tactics, rhetorics, and cultural expressions, the previous slow work of disseminating propaganda (many ideas to few people) now shifts to new expansive fields of agitation (few ideas to many people). However, these “few ideas” are far from superficial, but rather emerge from centuries-deep analyses and experiences made suddenly condensed, portable, accessible. Note how, for example, Direct Action Front for Palestine’s ubiquitous keffiyeh-trimmed banner, "When we breathe, we breathe together", succinctly reveals a long history of Black and Palestinian solidarities, underscored by Robyn Spencer’s essential BlackonPalestine Tumblr and a recent trip to Palestine by a delegation of Dream Defenders, #BlackLivesMatter, and Ferguson organizers. Most recently, Can't Touch This NYC's street action principles clarifies acts of solidarity that can oppose collusion with police repression, as well as foster space for movement self-critiques. To reconsider slogans as aphorisms, artwork as archives, and direct actions as staged dramas can interweave the best creative abolitionist practices of the Black Arts Movement that refused to isolate such spheres of expression from each other.

Particular attention to movement-archiving from below can decenter our focus from elite Eurocentric narratives to decolonial methods, in order to share lessons of the dispossessed and recognize the thousands of new leaders who have emerged. Although many unsung heroines and heroes of all colors created the conditions for a mass movement for racial justice to bloom, we now see the city government, non-profit industrial complex, and cultural elite quickly move in to hoist up a moderate tokenized leadership. Case in point: Millions March NYC, a phenomenal tuning fork moment for police abolition, is also a fork in the road between reformist and radical directions. As Arun Gupta recently argued, "While it is rooted in history of state violence against Blacks, Native people and Hispanics, racial identity [alone] doesn’t confer an advantage in organizing." Most of us are poor, scrappy, starving, swollen, not the right style or articulation or palatable shade for those who seek to defang and incorporate this movement. But as Messiah Rhodes has powerfully framed, "freedom may mean that the alienated, the mis-educated, the thugs, the orphans will be your equals." If we don’t assemble these counter-historical records and freedom dreams, those who don’t hold flashy photo-ops or cultivate Twitter handles like stock-portfolios may be forgotten in the fire next time.

To wrench justice from the mouth of the impossible, to prepare for the 22nd century tomorrow (in the words of Black Arts high priestess Nina Simone), we will need all of our creative tools and political experiences across generations and ethnic backgrounds. We need those who march for miles, those who stay home to care for infants and elderly, and those who are differently able to struggle. We need prisoner solidarity lessons from abolitionist movements and families whose members are encaged. We need to nurture strong communities not only to make the police obsolete, but to unlearn how we police each other in relationships, workplaces, classrooms, neighborhoods, and movements. We need to wield arts as purposefully as Copwatch cameras, resist arrests as deftly as we embrace friends and lovers, and continue to sing the names of our dead as vibrant political discourse. We need to see each bit of respiration as an act of warfare against a system that would rather see us extinguished. The fire of these last tumultuous months—of our long incendiary past—is not out, but its blaze has momentarily dimmed. Together, let’s keep breathing on the flame. Breathe. Breathe. Breathe...