August 2nd, AUS to NBO

August 17th, NBO to AUS

I was in Kenya until yesterday, and my mind is a jet-lagged jumble; perhaps that’s why I can’t focus on anything, why twitter’s mishmash of #Ferguson and everything else seems a more or less appropriate lack of order for my brain right now, and why focusing on one thing only brings another thing into view. Or maybe it’s a Koroga, the mixture of flavors and recipes and histories that isn’t meant to resolve or define or come into focus. Or maybe I just can't focus because I'm jet-lagged.

Theodore Roosevelt, uber-white-dad and former NYPD police chief, on the contagion in the heart of darkness:

“Then, from out of the depths of the Congo forest came the dreadful scourge of the sleeping sickness, and smote the doomed peoples.

Just before watching Vince Vaughan’s Delivery Man, on the long plane-ride (and before watching and then quickly stopping-watching 21 Jump Street), I watched Fruitvale Station and there’s a lot there to say about how the latter film imagines black life, and about the narrative structure in which it becomes thinkable in the film: on a train towards death, legitimated by procreation and employment and family. It’s a quietly superb film, devastatingly interested in the mixed temporality of life, where everything is contingent, provisional, uncertain, and temporary, until it isn’t: death is when you stop changing, growing, and feeling what you lack; death is when it is no longer possible to become what you aren’t.

I come back to this, the idea that “deep in the uncharted rain forests, deadly diseases are lurking”; it is a fear, “a notion,” because we have no reason to think it’s true. But because we do not know for certain that it isn’t, we fear it. It might be true, and because we need certainty—perhaps, we are the “we” that needs certainty—we must create certainty, using force. Exterminate the brutes. Order. Anything that is not order is a threat to order.

I watched The Lego Movie on the plane, and if you’ve seen it, you’ll understand why it’s popping into my head: Lord Business wants to glue everything together, so it can be just right, as it is supposed to be, total order. Naturally, the brief clip of what this looks like is a scene of gentrification and urban “renewal”: bulldozing old houses to build skyscrapers. There aren’t really any black people in the movie—everyone has “yellow” lego-faces, which basically means caucasian—but the “master builders” are led by Morgan Freeman (clearly marked phenotypically), and they articulate themselves in a negative relation to Emmet’s uber-whiteness, as well as being plagued by Cop.

In short: Business uses Cops to bring Order to the City, also drones and surveillance. I also watched Robocop, which is about Militrized-Cop bringing Order to the City so that Business can prosper, using surveillance and drones.

At the end of the Lego movie, Lord Business becomes a lovable white father. At the end of Robocop, the lovable white father shoots the bad cop and saves the day for his children. In Fruitvale Station, Oscar Grant is trying to be a father. In Delivery Man, Vince Vaughan is a father to hundreds of children without any evidence of mothers, and it turns out—in a way that only white privilege could find moving—the way to become a father is to choose to be a father because the power to be a special was always within you all along.

I went to AFRICA at a moment in which Ebola and Ferguson were the big narratives defining the present for me; I came back from AFRICA at a moment in which they still are. Yesterday, I watched Barack Obama—his grandfather was interned in a Mau Mau camp—describe the contagion that had exploded in a black reverse-suburb of St. Louis, and the efforts to contain and suppress it. He played good cop.

He was born in the United States, not in Kenya.

The British put Jomo Kenyatta in indefinite detention when they thought he was the leader of Mau Mau; he wasn't, and when they realized it, they let him out to be the first President of Kenya. He played good cop to their bad cop.

Jomo Kenyatta, 1962: "Mau Mau was a disease which had been eradicated, and must never be remembered again."

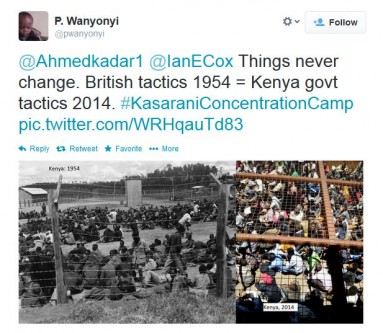

Jomo Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru Kenyatta, is now the president of Kenya, and “security” is the watchword. This word is spoken in an American accent, I think. Operation Sanitize is the effort that Kenyatta has launched to contain the contagion of Somali terror, which seem mainly to derive from a desire to put Kenyan-Somalis in cages, or to expel them back to Somalia. When his father did the same, it was called the "Shifta War"

Jomo Kenyatta’s son, Uhuru Kenyatta, is now the president of Kenya, and “security” is the watchword. This word is spoken in an American accent, I think. Operation Sanitize is the effort that Kenyatta has launched to contain the contagion of Somali terror, which seem mainly to derive from a desire to put Kenyan-Somalis in cages, or to expel them back to Somalia. When his father did the same, it was called the "Shifta War"

IPOA: “a number of these attacks occurred within the locality of Nairobi’s Eastleigh Estate, a suburb largely inhabited by Kenyan Somalis and which, security sources apparently believe, also plays host to a large number of illegal immigrants from Somalia. In one such attack on 31st March 2014 for instance, three massive explosions occurred simultaneously within the Estate, killing 6 people and injuring 31 others.

As a result of the growing insecurity, on 5th April 2014, the government launched a second internal security operation dubbed OPERATION SANITIZATION OF EASTLEIGH, which was to be carried out under the aegis of the National Police Service. This Operation was largely designed to be carried out around Eastleigh Estate and other areas perceived to be hideouts for illegal immigrants. According to documents availed to the Authority, the declared purpose of this new Operation was to flush out Al- Shabaab adherents/aliens and, search for weapons, improvised explosive devices (IEDs)/explosives and other arms so as to detect, disrupt and deter terrorism and other organized criminal activities.”

Some have suggested that this is all really about the threat of Somali capital, about seizing and controlling the city.

Rep. Phil Gingrey (R-GA): “Reports of illegal migrants carrying deadly diseases such as swine flu, dengue fever, Ebola virus and tuberculosis are particularly concerning.”

In Nairobi, commercial public space is heavily policed: there are metal detectors, guards who screen your car and bags (with metal detector wands), and one feels very clearly and distinctly the difference between safe, guarded spaces—inside—and the danger of the streets. There are traffic cops with assault rifles everywhere. Cops with guns are banal; surveillance is routine. To pass from the street into the inside, you must be screened.

The United States is widely understood to have "interests" in the Kenyan war against Somalis in Somalia, and in the "terrorist" screening efforts in Kenya.

When African leaders came to Washington a week ago, Obama announced that he was committed to “containing” the Ebola outbreak. Not stopping or curing; the word used was “containing.”

In Kenya, lots of people get killed by the police, and Ebola is not really a reasonable thing to be afraid of.

In Kenya, lots of people get killed by the police, and Ebola is not really a reasonable thing to be afraid of.

Ferguson is contained in St. Louis, is a container within St. Louis, contains in St. Louis.

The 1976 Ebola Outbreak, visualized.

Of the quasi-Ebola film Outbreak, Roger Ebert wrote:

Of the quasi-Ebola film Outbreak, Roger Ebert wrote:

“It is one of the great scare stories of our time, the notion that deep in the uncharted rain forests, deadly diseases are lurking, and if they ever escape their jungle homes and enter the human bloodstream, there will be a new plague the likes of which we have never seen.”

This is not a bad review; it’s a good review, or at least an accurate one that understands why “our time” is frightened of dark contagions escaping from “the jungle,” why it becomes a matter of bio-political life-and-death that “we” keep “the human bloodstream” pure from lurking dangers in the uncharted heart of darkness:

"Outbreak opens 30 years ago, in Africa, as American doctors descend on a small village that has been wiped out by a deadly new plague. They promise relief but send instead a single airplane that incinerates the village with a firebomb. The implication is that the microbe is too deadly to deal with any other way”

There is no other way than to exterminate the brutes, you see: the threat is in their very blood, and even one drop of it will contaminate us.