As more people found a place at the table, the concern became that of finding a place for the table

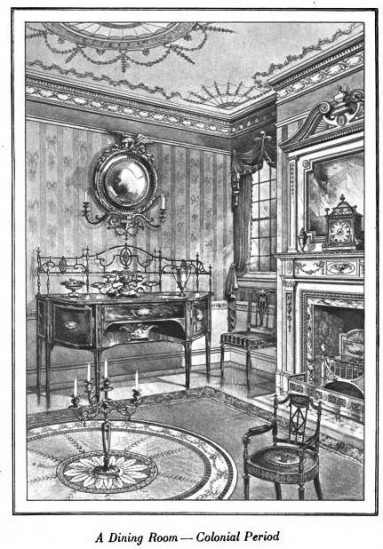

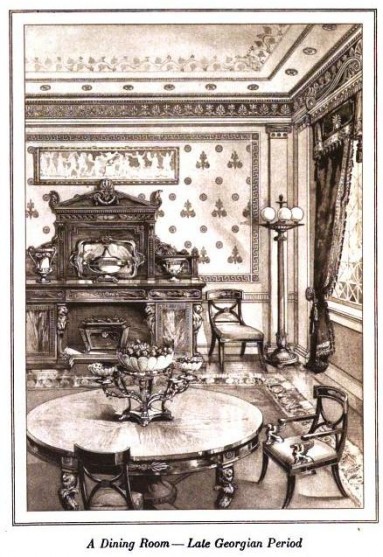

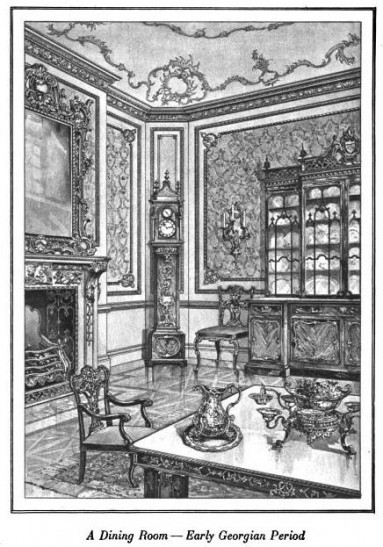

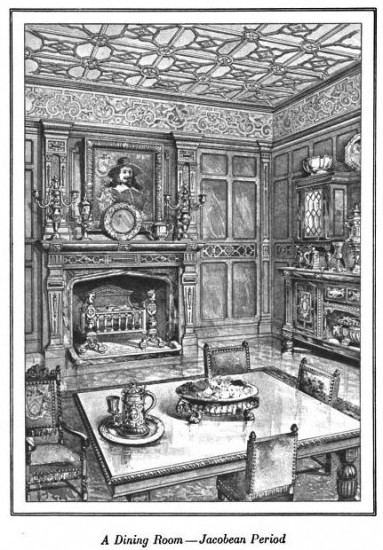

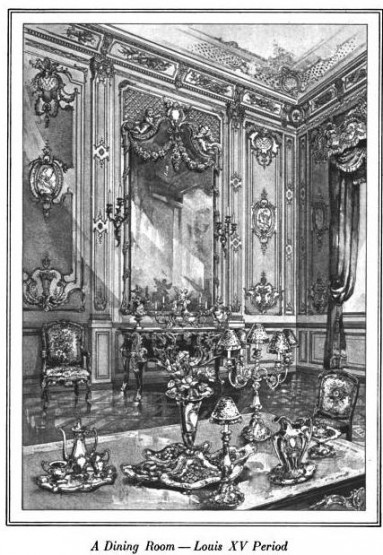

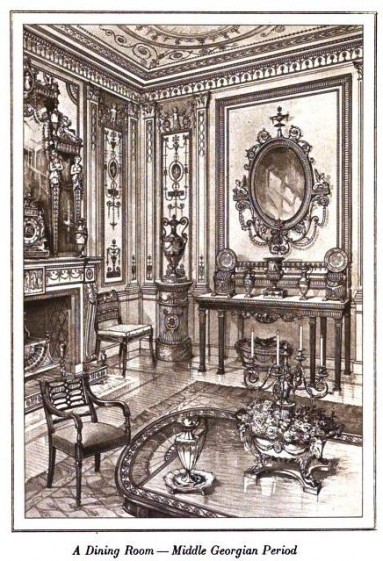

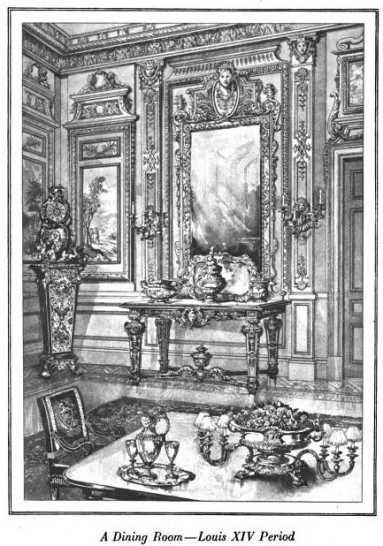

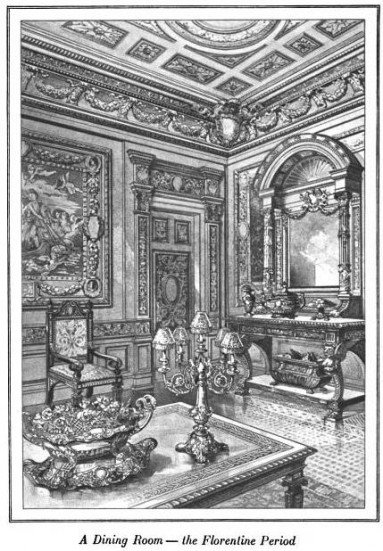

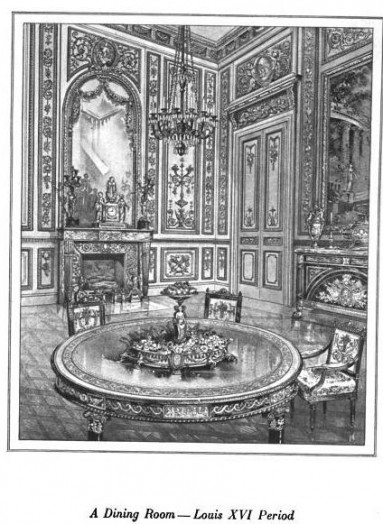

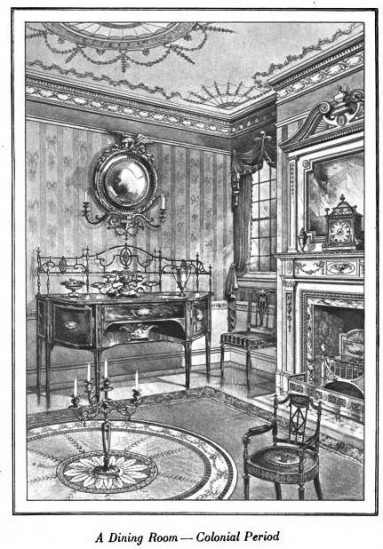

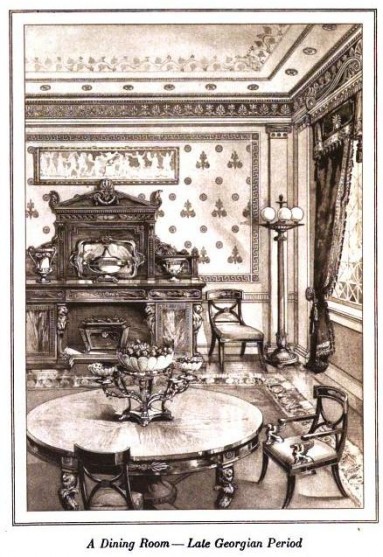

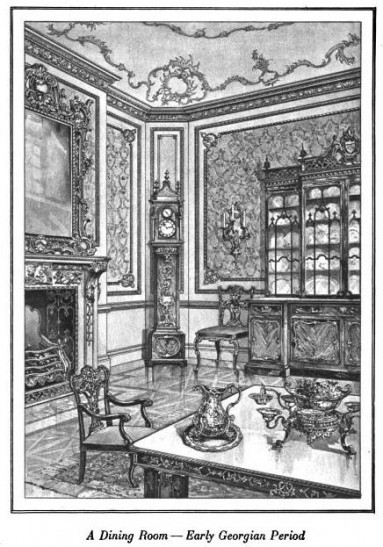

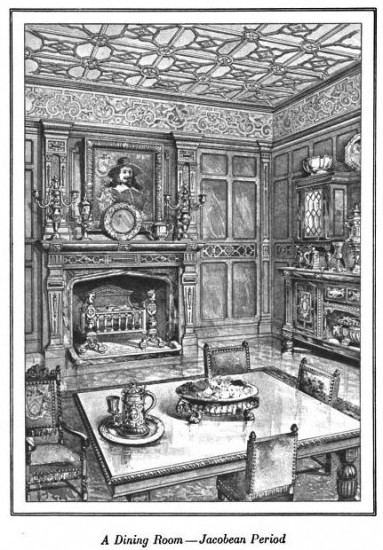

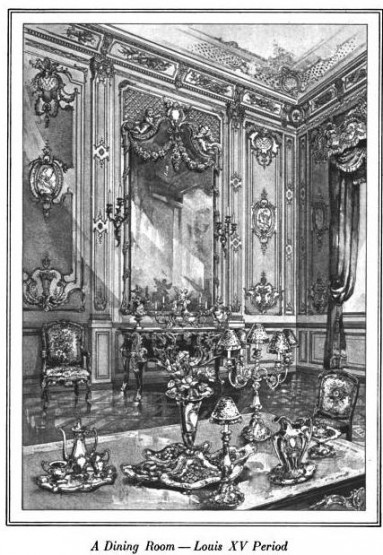

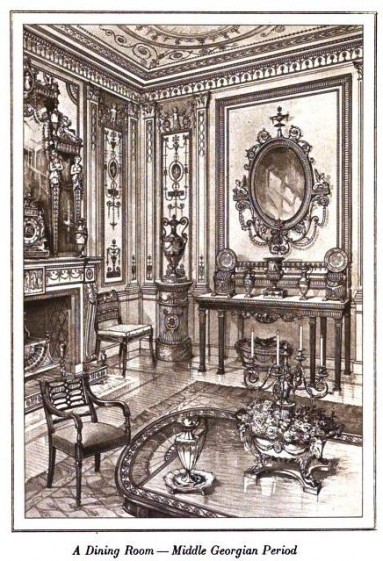

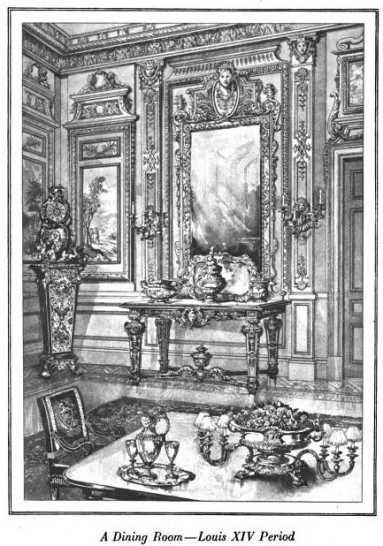

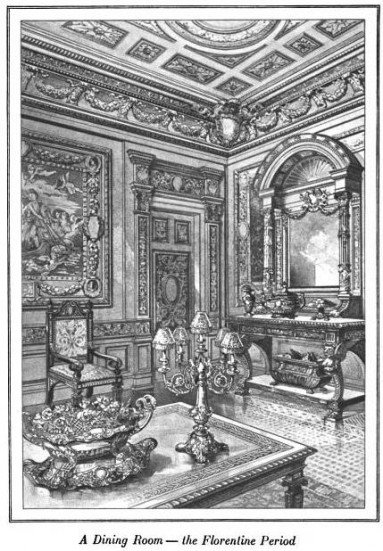

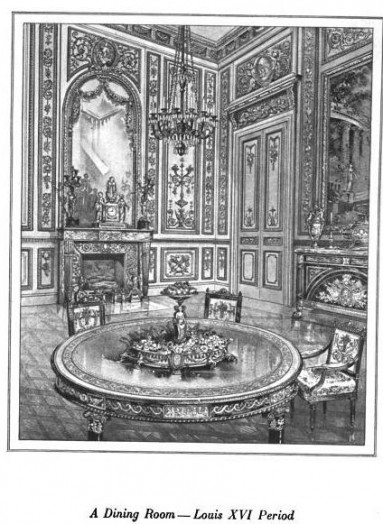

Illustrations from Silver for the Dining Room (1912)

"In itself and in its consequences the life of leisure is beautiful and ennobling in all civilised men's eyes." --Thorstein Veblen

For the first time in my adult life, I have a something approaching a dining room. Accustomed to eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner on a breakfast bar, coffee table, or some other makeshift means of support, I find myself strangely delighted by the idea of sitting down each evening at a table that seats four in a space reserved only for eating. For one, meal time is easier. (There’s no better way to test your coordination and patience than carving a turkey that’s perched atop a folding table.) I’d say having a dining room makes me a fully fledged grown-up, were it not for the fact that I still rent. Precarity is Neverland.

Yet even in centuries past dining rooms were something of a novelty. Only the wealthy had them. The bulk of humanity, meanwhile, spent most of history wriggling, with varying success, toward the same distinction.

"'A clean table cloth and a smiling countenance.' The former may be commanded; but there are dinners over which the mistress of the house cannot smile; they are too bad for dissimulation: the dinner is eaten in confusion of face by all parties." --From Practical Housekeeper (1853)

"'Now bring me a splendid dinner,' he ordered. 'We have a proper table service, let us have something good to eat.' He sat down upon a chair; it turned to gold. His clothes had already become of gold, so stiff that he could hardly move in them. Dinner was brought in. His chair was too heavy to move, so he had another placed at the table and sat down. That seat also became gold in a moment. He took up a piece of bread; before he could break it, a change had taken place, and it was hard gold. He laid his hand on a bunch of grapes; they were so heavy that he dropped them with a clatter of gold upon the golden dish." --Charles Dannelly Shaw, Stories of the Ancient Greeks (1903)

The Greeks were among the first to recognize that eating in secluded comfort reinforced status and class cohesion. Elite men of the most powerful

poleis gathered on fragrant evenings in rooms especially designed for feasting. These rooms accommodated no more than eleven couches of stone or wood, each of which in turn accommodated no more than two men. Youths sat on the ground. Young and old alike quaffed diluted wine and munched honey cakes and chestnuts -- all fuel for ribald and learned discussions of matters philosophical and romantic.

Ancient Romans similarly took their meals in a special room called a triclinium, whose couches had evolved to accommodate women as well as men. Whim and the season determined their location. In the stifling Mediterranean summers they were chosen for their ability to catch breezes; in winter, to block drafts. Some of them might offer a view of the sea; others, vast plains. The Romans sometimes even set up their dining rooms outdoors in order to enjoy al fresco their swallow’s tongues and other delicacies. The most luxurious dining spaces bred ease and amazement in equal measure. Triclinia in Pompeii featured fountains from which water splashed and streamed from each table. Guests of one Loreius Tiburtinus plucked tidbits from large basins in rooms bearing brightly painted images of mythological figures.

"As for the tarts, I didn't eat a mouthful of them, but I just smeared myself up with the honey, I can tell you! At the same time, there were peas and nuts, and apples for each of us. I carried off two of these last, and I have them here in my napkin. Just look, for if I shouldn't carry away home something for my pet slave, I should get a blowing up." --Petronius Arbiter, "Trimalchio's Dinner" (late 1st century AD)

Such vivid appointments obscured a dark reality. A well-to-do Roman household could include as many as 400 slaves, who did everything from choosing menus to arranging and presenting parting gifts to guests. In all activities grace was the watchword. The slightest faux pas invited brutal punishment.

"Para was invited to a Roman banquet, which had been prepared with all the pomp and sensuality of the east: the hall resounded with cheerful music, and the company was already heated with wine; when the count retired for an instant, drew his sword, and gave the signal of the murder." --Edward Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-89)

If, writes historian Roy Strong, “game was underdone or the fish poorly seasoned the cook (who actually ranked fairly high in the slave hierarchy) would be stripped and beaten.” Strong relates an instance during a dinner given by a friend of the Emperor Augustus. A cupbearer broke a crystal goblet. For this offense he had his hands cut off and hung from his neck. He was then forced to parade among the diners, and thereafter thrown alive in a fish pond as food for lampreys.

"The main meal of the noble was at noon or soon after. There was one lighter meal in the morning and another rather late in the evening. The dining table consisted of several boards, removable as soon as the meal was over ... There were spoons and some knives, but forks were unknown. Cakes of barley or wheat were served, game, bacon, pork, fish, or possible, although not probably, 'the roast beef of old England' might be part of the rather limited menu." --Roscoe Lewis Ashley, Medieval Civilization: A Textbook for Secondary Schools (1916)

A bit kinder than their Roman forebears, medieval men and women presided over meals altogether less violent.

When mead ran free and blood hot, however, there was no telling what might happen.

Yet what they gained in civility they lost in comfort. Even the most powerful lords, though they might surround themselves with lush tapestries and lovingly crafted pastries packed with everything from magpies to midgets, ate in drafty, smoke-filled halls. “Magnificence there was, with some rude attempt at taste,” notes Sir Walter Scott of this era: “but of comfort there was little, and, being unknown, it was unmissed.”

"Comfort is the only thing our civilization can give us." --Oscar Wilde

Comfort grew with increased trade, and with it changed notions of home and hearth. Parlors, “dining chambers,” and other spaces amenable to dining began appearing in architecture plans. Each nation seemed to have its own idea as to what constituted a proper dining room. The great Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti wrote that it “should be entered off the bosom of the house,” advising further that, “[a]s use demands, there should be [a dining room] for summer, one for winter, and one for middling seasons.” Some two centuries later Englishman William Sanderson would recommend that a “Dyning-Roome” be hung with pictures of kings and queens.

"Every recession solves a certain number of problems, removes pressures, and benefits the survivors. It is pretty drastic, but none the less a remedy. Only good land continued to be cultivated (less work for greater yield). The standard of living and real earnings of the survivors rose. Thus in Languedoc between 1350 and 1450, the peasant and his patriarchal family were masters of an abandoned countryside." --Fernand Braudel, The Structures of Everyday Life (1979)

"The fact that political ideologies are tangible realities is not a proof of their vitally necessary character. The bubonic plague was an extraordinarily powerful social reality, but no one would have regarded it as vitally necessary." --Wilhelm Reich

For all the talk of appointments fit for royalty, perfection of the dining room came only with the rise of a middle class. Between 1350 and 1560 people began to eat and live better, thanks in part to greater availability of meat and dairy products in the wake of the Black Death, and to the development of a market economy. Where meat and milk abounded labor was scarce. Pay went up as a result. In some parts of England, for example, laborers saw their wages grow four or fivefold in just a few years. The workers of Cuxham Manor in Oxfordshire went from earning two shillings a week in 1347 to more than 10 shillings a week three years later.

"When the lamp of antiquity flickered out in the Dark Ages, it was the middle class that led mankind forward to the new day. It was the middle-class Protestant who brought the conscience of the world to bear again upon the life of the spirit. When England set its constitution above its King, when the American colonies established the people as the origin of all justice, when France built up the foremost European republic, it was always the middle class in whom the movement began -- and ended. The institutions of civil liberty are the creation, not of the proletariat nor yet of capitalists, but of those who are neither rich nor poor." --John Corbin, The Return of the Middle Class (1922)

With higher wages came increased consumption of goods, among them furniture and cooking utensils. In time there developed a culture peculiar to the newly affluent. One of this culture’s hallmarks, the dining room offered a place where family members could discretely enjoy each others' company. As such, it reflected what Italian theorist Mario Praz calls

Stimmung, a German word that denotes the sense of intimacy and personal character evoked by a room’s arrangement and decor.

Recipe for "Soup au Bourgeois" from The London Art of Cookery (1804): 'Take twelve heads of endive, and four or five bunches of celery; wash them very clean, cut them into small bits, let them be well drained from the water, put them into a large pan, and pour upon them a gallon of boiling water. Set on three quarts of beef gravy, made for soup, in a large saucepan: strain the herbs from the water very dry; when the gravy boils, put them in. Cut off the crusts of two French rolls, break them and put into the rest. When the herbs are tender, the soup is enough. A broiled fowl may be put into the middle, but it is very good without. If a white soup be liked better, it must be veal gravy."

Victorians would take

Stimmung to an often unbelievably cluttered extreme. They spent lavishly on their dining rooms, outfitting them with upholstered chairs, mahogany sideboards, pewter jugs, bone china, linen napkins and tablecloths, and silver cutlery. They read architectural guides and kitchen utensil catalogs as thick as phonebooks. Mealtime for them was an event, and they staged the satisfaction of their appetites in surroundings as comfortable as they could afford. Why they did so is the subject of the second part of this history.