That Snowpiercer is an allegory for capitalism and revolution has been widely and well-discussed—for example, see Emma and Peter Frase—and I already knew it when I went to see the movie. So did Unemployed Negativity:

“I scrupulously avoided reading any reviews of Snowpiercer once I became intrigued by the basic premise. Despite this, and not reading anything after seeing it this afternoon, I was aware, in that way we become aware of things through an almost social media osmosis, that it was quickly being heralded as a new film about the 99% and the 1%, about social inequality, and, more importantly, about revolution.”

This reading is easy, and correct: the train is the capitalist economy, and while Curtis and company initially set out to seize the means of production (the engine), the revolution stops being reformist when Curtis makes a Big Discovery about how the train works, at the end, and decides to go large instead.

As an allegory, then, the movie is insistantly anti-reformist, in the terms by which “reform” and “revolution” are understood to be different and opposite things.

Such a system cannot be improved by reforming it. Since eating kids is about as close to a universal taboo as we’re likely to find, a system based on that form of consumption is impossible to justify; as Ed Harris notes, while frying up a nice piece of what I would like to assume is human baby—you have to be a little bit insane to live on this train. In such a context, “reform” is simply a matter of making it operate more efficiently. You can replace the engineer with a new engineer, but it won’t be different when “we” run the train; the engine remains, and its needs will always dictate what the train needs to function. You will still need to put babies in its belly.

Is a civilization that survives by auto-cannibalism sustainable? Is it worth sustaining? This is a question that the movie raises at several points, particularly when we learn why so many of the passengers lack arms and legs. At one point in the origin story of the tail-section, we are told, Gilliam and others cut off their own limbs to feed the others—a story I’m tempted to regard as more of a

This is the truly despair-inducing ending, then, Curtis’ realization that there is no alternative: when he finally meets the Wizard of Snowpiercer, he discovers that the thing he’s been fighting and bleeding for—to replace the bad leader with the good leader—is a mirage. Even the White Males who have symbolically castrated themselves and become mother figures instead—even Gilliam, who cuts off his arm and feeds it to the babies—turn out to be a part of capital’s mode of reproduction by auto-cannibalism. Gilliam and Wilford are Curtis’ parents—as he is traumatized to discover—and even the revolution is an integral part of the train. Only the engine is eternal.

This fact, however—as the ending reveals it to be a fact—is also what makes the movie anti-revolution. There is no alternative. Kill yourself. Or, instead of killing yourself, perhaps you should give your body to the others, so that they can live? That must have been Gilliam’s thought process, as well as the two children we see “working” in the engine. It’s a reasonable train of thought, and it leads to insanity. But what other choice is there?

* * *

Let’s back up a bit. For most of the movie, I was irritated by what seemed to be a hole in the plot: what are the tail-section people even for? They are so obviously extraneous to the operation of the train that they cannot stand for an exploited proletariat in the classical sense. They do not seem to provide anything with their labor, because they do not seem to labor. The front section passengers do not need them. So why haven’t they just let them die? It certainly doesn’t seem to be mercy.

A part of what they provide, it turns out, is psychological comfort. The rest of the train has everything it could want, because desire cannot survive without lack to give it meaning. If you have everything you want, you don’t have want at all. Conversely, to believe that you don’t want for anything, “nothing” needs to exist to make extraneous desire unthinkable. This is the first purpose of the tail section: to convince the rest of the train that they have everything they desire (and want nothing), the tail section passengers must exist so as to provide a zero-point from which pleasure and desire can be measured. In this way, by creating a space in which desire and frustration and hope and fear can actually still be exercised—because the first class passengers can never change or progress or grow or evolve—it becomes possible for the 1% to forget that they are standing still on a moving train.

In this way, even the “revolution” only keeps the system sustainable. Without occasional violence, there would be only pleasure, and pleasure fades when there is nothing but pleasure. At a certain point, you need blood; the revolution provides that blood, as does counter-revolutionary violence against the bare-life tail-section passengers.

Let’s not forget, after all, that while we see scores of lounging, decadent drug-addled first-class passengers dissipating themselves in pleasure, as our heroes navigate through the bowels of capitalism, we also see at least as many black-masked, hatchet-wielding thugs, first class passengers who are ready, willing, and able to kill on command, and who apparently live for that command. Even the party-raver passengers turn into a murderous mob when given the opportunity to do so. Even Tilda “Ayn Thatcher” Swinton pivots easily from punching down to punching up; given the opportunity, she’s as happy to live by killing Wilford as she is to live by killing passengers. They are one and the same thing; killing is what makes her alive.

Snowpiercer is a truly chilling dystopia, then, because its world is fully self-contained, and sufficient. But the most insane thing about it is that it makes sense. And it crystallizes something firghtening about the psychic geography of late capitalism, a technologically-enhanced state of affairs in which the function of the oppressed masses is less and less to work and be exploited than to be excluded and to suffer.

* * *

Does this make the movie a Marxist “allegory” for capitalism, as so many of its readers have claimed? In one sense, yes, and even the director has said so. By using a dystopian future to represent capitalism, it argues that capitalism is a dystopic machine, that it keeps us alive by allowing us to sustainably eat ourselves. The worst thing about capitalism, in other words, is that it does keep us alive: to stay alive, we must be capitalist, but the more we eat ourselves, the less we actually die. Accelerationists might take up the part of Marxism which suggests that capitalism is unsustainable, and will inevitably accelerate until the point it goes off the rails, and use that to argue that we should go ahead and speed up the train. But the truly horrifying possibility is that this is not what will happen, and that the faster we go, we only auto-cannibalize ourselves more efficiently as the system closes itself more tightly.

In a way, however, “allegory” is the wrong word. Allegories always flow out of the reality principle that makes a narrative subterfuge necessary; to unmask the fact that a story which seems to be about one thing is actually about another thing, is to demonstrate that there is something unspeakable that you can only suggest by misdirection and implication.

What does Snowpiercer allow us to say? What relief does it provide? Does it tell us that the one percent are eating the babies of the poor? Yes, but we already knew that, and we can say so if we want. (Go ahead, say it; no one will stop you). Does it tell us that capitalism sucks and that we should smash the state? Yes, but the cold war is over and that kind of radical utopianism doesn’t have quite the aggressive subversiveness that it once might have had. When the Soviet Union existed, there was (or seemed to be) an alternative, so being anti-capitalist could mean being for something else. Does it, today? For an awful lot of people, it doesn’t, because there is no alternative. Be as anti-capitalist as you like, those people now say; read Thomas Picketty, if you want. You still have to shop at the company store.

Calling Snowpiercer an allegory for capitalism, then—and especially reading it as an argument for revolution—elides the things that make it scary. If a director can make a movie about how capitalism is auto-cannibalism, and say so, then it’s not an allegory for capitalism. How can the train be a metaphor for late capitalism when it literally is, in the movie, the form that capitalism takes after climate change? It is the latest possible kind of capitalism, a capitalism that no longer makes anything other than pain and suffering. The train is the capitalism that it has eaten up the entire world, and is now just living off its own stored reserves of fat.

Snowpiercer is not about the revolution we might have today, then; it’s about the time after revolution has ceased to be possible. As a dystopic future, it can even be recuperated into a call to save the present, precisely so we don’t get to the point where Snowpiercer has already gotten. It could be a call to revolution: what we need to do is change the system. In this way, however, it isn’t “about” contemporary capitalism at all. Or if it is, then it’s already too late; if children are the only food sources left, then our choice is no choice: we can kill ourselves or eat ourselves, each of which implies the other.

* * *

My favorite part of the movie is the moment when Curtis reveals the Big Secret about his dark past, and Nam’s response is to thank him for telling such an interesting story.

Curtis thinks he’s just blown Nam’s mind, by revealing the dark truth at the basis of everything. But Nam already knew that Soylent Green was people. In a way, so did we. Cannibalism is such an omnipresent over-text of the movie that the story of the back-of-the-train’s primitive accumulation of protein is not such a stunning revelation. In the saw way, Curtis’ deep shock at discovering what the protein bars are made from—Bugs!—demonstrates the kind of naivete that makes him a plausible revolutionary leader, a romantic idealism that makes him exactly the kind of fool that Gilliam would pick to lead a sham revolution. What did he think they were eating? In some parts of the world—like Korea, to pick a totally random example—insects are recognized to be a perfectly healthy and nutritious source of protein. Would you rather eat children? What if your “clean” food was made in sweat shops? (Breaking: it is!)

Curtis thinks he’s just blown Nam’s mind, by revealing the dark truth at the basis of everything. But Nam already knew that Soylent Green was people. In a way, so did we. Cannibalism is such an omnipresent over-text of the movie that the story of the back-of-the-train’s primitive accumulation of protein is not such a stunning revelation. In the saw way, Curtis’ deep shock at discovering what the protein bars are made from—Bugs!—demonstrates the kind of naivete that makes him a plausible revolutionary leader, a romantic idealism that makes him exactly the kind of fool that Gilliam would pick to lead a sham revolution. What did he think they were eating? In some parts of the world—like Korea, to pick a totally random example—insects are recognized to be a perfectly healthy and nutritious source of protein. Would you rather eat children? What if your “clean” food was made in sweat shops? (Breaking: it is!)

When Curtis tells Nam his story, he thinks its shameful, as he had another choice. He still thinks that a benevolent leader could fix things, and make an equitable distribution of resources. But Nam knows what Curtis doesn’t; while Curtis was eating people and then trying to forget, Nam was in the front part of the train, watching it happen, planning, and building security doors. Nam has decided that there is no alternative, and never was. That’s why he has a different plan: to blow up the train and destroy humanity, forever.

That’s not revolution. That’s the end of the world. And let’s take a moment and remember what a relief that moment was, what a catharsis. Everybody in this movie needs to die, and they all do, thank God. That’s the real ending of the movie, and it’s pleasurable to watch, a relief. The movie fades to black before we see the polar bear eat those two kids, but let’s not fool ourselves: those two kids are not going to wander off into a new Eden and repopulate the earth (and not only because there are only two of them, though that lack of genetic diversity is one of humanity’s many death sentences here). Nature is about to eat the children that were just saved from being eaten by the train. A polar bear is not a sign of hope, because polar bears eat people, and, anyway, how is a pair of children who have never been off the train—have never even seen dirt—going to be able to live on what is basically Antarctica? Those kids are already dead, in days, if not hours, if not minutes.

The best case scenario is that they don’t die yet. If they survive by eating the (conveniently refrigerated) human meat they find in the various trains around them—or in the frozen cities of the frozen world around them—there is nothing like a utopian vision to be found in this scenario, only another primal tragedy that either starts the whole damned thing moving again, or keeps it moving a couple more rounds. At best, they are still parasites on what’s left of industrial capitalism, the roaches that survived the nuclear holocaust. They are not, and will not be, Inuits or any other variation on the paleo-primitive savage; Nam’s dream that it is possible to survive outside the train, if you just remember to wear a coat, is totally totally unhinged, the sort of dream that a guy who’s been living in a drawer and doing drugs would dream. The fact that he has made some observations out the window of the train does not make him a reliable climatologist.

At the same time, his insane choice is as close to sanity as you’re going to get on this train. We don’t know he’s wrong, just like we don’t actually see the polar bear come over and snack on the kids. His choice is the correct one within the logical box the film has constructed. A tiny, microscopic chance that things are getting better outside—a desperate and unfounded faith without reason—is actually a better bet than hoping that things will get better from within, because we know that is not going to happen. That train is fucked, as Yona observes; either there is salvation outside or humanity is better off not existing at all. We have no reason to believe it’s the former, but if it isn’t—if there really is nothing else—then we have lost precisely nothing by the discovery Humanity is a terminally ill 95-year old living in tremendous pain with extremely low quality of life. It’s time to pull the plug. Anything is better than this, and so is nothing.

Why do we like watching a movie that fantasizes about the end of all human life? Freud had to invent the “death drive” to explain what the pleasure principle couldn’t, the fact that people sometimes put themselves in danger on purpose, and seem to feel an attraction to death that cannot be explained in terms of a utilitarian economy of pleasure-maximization. Suicide is irrational, yet people do it, and people also seem to like to tantalize themselves with death. As Freud noted, then, there is a death drive: sometimes death is a mercy from unlivable life, and sometimes we take risks because it makes us feel alive.

Why do we like watching a movie that fantasizes about the end of all human life? Freud had to invent the “death drive” to explain what the pleasure principle couldn’t, the fact that people sometimes put themselves in danger on purpose, and seem to feel an attraction to death that cannot be explained in terms of a utilitarian economy of pleasure-maximization. Suicide is irrational, yet people do it, and people also seem to like to tantalize themselves with death. As Freud noted, then, there is a death drive: sometimes death is a mercy from unlivable life, and sometimes we take risks because it makes us feel alive.

This is not to say that we really want to die. Death is the ultimate outside to living experience, the absolute unknowable; we cannot want it, therefore, because we cannot know what it is. But “death” can be the fantasy that drives us: we may not really want to die (and who knows what we really want), but the idea that “I wish I was dead” can be a way to articulate the unbearable reality of a life we cannot bear, and yet for which we have no alternative. Death is the ultimate alternative, and an inevitable one. So when nothing in life suggests that another world is possible, the idea of death can serve as the alternative that is, in the end, not only possible, but inevitable.

This is why the movie ends with everything being blown up, and why it’s such a relief to see the entire train be destroyed. Nothing good can or will come from that train, and its total destruction is a relief. For the viewers, we get death without death: we don’t actually have to destroy the entirety of humanity to enjoy the fantasy of all the things we hate about ourselves, as a species, being obliterated. By making that train the crystallized encapsulation of everything that is awful about late capitalism, Snowpiercer lets us watch it burn. This is what movies do, let us enjoy the fantasy of something we can’t really want in reality, or something we want without wanting all of it.

In this way, Snowpiercer is less an allegory than it is an extended, narrative form of ruin-pornography. As critics like Fredric Jameson or Slavoj Žižek like to proclaim, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” but this bit of conventional wisdom is true without being quite as revelatory as it can sometimes seem.

Snowpiercer is different mainly because it covers these ruined cities with snow. But look around

Snowpiercer is different mainly because it covers these ruined cities with snow. But look around

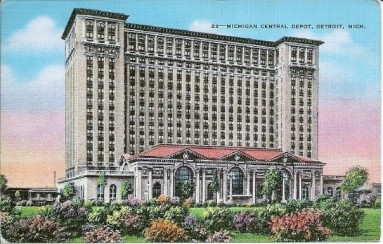

In a way, that’s sad. But the dream of high modernism was always already also a nightmare. See how little you have to change the old Michigan Central Station to make it into the new one, the dead one:

People can’t live in either of them, but one of them has color. Our cities have always been concrete sarcopoli, for as long as they’ve been what they are; without the countryside outside of them—feeding us with the living material of the earth and providing somewhere to dump our waste—they would become concrete tombs. And so, the dark dreams of industrial capitalism have always been the knowledge of the outside that is required to keep the radically un-closed system viable, the death camps, prisons, workhouses, and meat factories that “we” have always subjected “them” to. And we have always feared that we would become them.

People can’t live in either of them, but one of them has color. Our cities have always been concrete sarcopoli, for as long as they’ve been what they are; without the countryside outside of them—feeding us with the living material of the earth and providing somewhere to dump our waste—they would become concrete tombs. And so, the dark dreams of industrial capitalism have always been the knowledge of the outside that is required to keep the radically un-closed system viable, the death camps, prisons, workhouses, and meat factories that “we” have always subjected “them” to. And we have always feared that we would become them.

White people began to say “Never again” after the holocaust, because for the first time, white people worldwide had to face the possibility that it could happen to them. It’s no coincidence, then, that only the white men in the movie want to build a utopian closed system, with themselves in charge. They believe in it, believe that it’s possible. Those who have been “othered” are much more cynical, and have much more modest goals: keeping their own kids alive.

(via)

(via)

This is a movie in which there is no alternative. Is there no alternative? If so, Margaret Thatcher was right.

What would a revolution look like? What would an after capitalism actually be? It’s reasonable to be skeptical. None of us have ever seen earth, and in that way, we’re like Yona: our food comes from the supermarket, and when the shelves go bare, we will probably starve to death. That’s what the end of capitalism could look like, whether it’s brought on by climate change or some other energy crisis. And it will end. There is no such thing as a perpetual motion machine, and we’re running out of the carbon energy that industrial capitalism was built on. By the same token, Wilford thinks he’s built a truly closed ecology, but that dream is at least as crazy as Nam’s, just as much a fantasy. Everything stops, eventually, and that’s as true of capitalism as it is of our individual lifespans. Even the universe will eventually die of heat death.

We spend most of our time and energy acting as if it isn’t, and as if we have the power to stop it. We act as if we can live forever, and even our risk-taking might be, in part, an effort to forget the fact that we know we can’t: I choose to smoke because choosing to die reassures me that I have a choice, that I could also choose not to die.

We also tend to pretend that our current civilization can survive climate change. Can it? I don’t know how anyone can reasonably think that we’ve got more than a century or so before the train goes completely off the rails. Trains only look unstoppable, which is one of the great things about Snowpiercer’s metaphor: sure it can blast through obstacles, if they’re positioned just right, but it doesn’t take all that much lateral force to knock it off its tracks. And once that happens, it’s not going to right itself. Trains don’t go back onto the tracks, and climate change doesn’t reverse itself. It’s a runaway train, and once we hit the point of no return, we’re not going to return. When climate change really happens, that’s the end of everything we are and know. “We” won’t survive, and whatever survives—which is unlikely to be human—will not be “us.” Climate change is species death, probably, and civilizational death, definitely.

* * *

We shouldn’t necessarily let that get us down, though. I mean, did you think you were going to live forever? Did you think your kids were? If so, cool story! Death is the thing we always live with and no one gets out of here alive and so forth; you can evade it, for a while, but it’s the only thing more reliable than taxes, because even rich people die. Etcetera, after cliched etcetera.

The only real question is what to do with that fact. And the answer is: not much. You can’t. Death is the negation of doing, by definition. Even suicide is not death, but the prelude to it, the thing you do just before all doing stops. But that’s why utopian thinking threatens to become dangerously unhinged from reality if it believes in itself too much: imagining that you can live through death is a good way to turn life into death. A Thousand-Year Reich is built on death camps, pyramids are built with slave labor, the Soviet Union with gulags, and the neoliberal End of History was the beginning of the United States’ great explosion of prison-building and a global forever war on terror.

If nothing else, one pleasures of Snowpiercer is that it punctures the illusion that rich people can buy immortality, something we 99%ers enjoy because we know for damn sure that we can’t and won’t. The moment when Curtis attacks Tilda Swinton rather than trying to save his little brother Edgar, for example, is a moment of great pleasure for the audience, and that’s something the movie forces you to confront: you wanted her to die more than you wanted Edgar to live. That’s the reason she’s so awful, why the movie puts all those unendurable platitudes about order into her mouth: she believes, as does Ed Harris, that there is order in the universe, and we—like Curtis—want to smash that smug belief more than we want her to be right. We want to smash it because it’s the thing we wish we could believe in, but can’t. To want him to save Edgar, we would have to think that there was hope, and we don’t; enjoying Tilda Swinton’s death, on the other hand, is to feel justified in nihilistic despair. This is a movie about nihilistic despair, the nihilistic despair that is the only reasonable response to the fact that we’re all going to die and everything we love is going to disappear.

But why have a reasonable response to that fact? What has “reason” ever done for us, other than produce utilitarian arguments for the liquidation of human beings and the commodification of everything? Reason makes it possible to declare that the deaths of children are “worth” it, whatever the fuck “it” is supposed to be. Reason makes despair possible, the same way aspirations to immortality make death unbearably sad. Reason helps us get nowhere and never stop going there.

The problem with calling the movie an allegory is that allegory doesn’t tell you anything you didn’t already know, and it hides the thing you didn’t realize it was persuading you of. Allegories are closed ecologies. If Snowpiercer is a movie about capitalism, then we already know what it is, and says, because we already know what we know about capitalism. If you think a death-train of the damned in a post-apocalyptic hellscape is an allegory about capitalism, then it’s because you think capitalism is a death-train of the damned in a post-apocalyptic hellscape. But if everyone knows that the train is an allegory for industrial capitalism—and everybody certainly seems to—then it’s not a secret, and not the kind of allegory Jameson was talking about when he described anti-capitalism as our political unconscious. It’s anything but the kind of unspeakable, repressed truth that we all pretend not to know, even to ourselves; the fact that the train is capitalism is the thing we allow ourselves to talk about because we’re afraid to talk about the real thing it is, which is death, our fear of death, and our desire for the thing we fear. We’re all going to the same place, and we’re all going nowhere at the same time; there is nothing outside of life, nor is it enough. There isn’t a happy ending, just an ending. And so forth.

This movie takes for granted that there is no alternative, and that’s the thing we shouldn’t take seriously. It’s just a movie, a movie built on the ability of a writer to imagine a scenario precisely in the way he chooses. In Snowpiercer, there is nothing outside of the train: life is just measuring time until death. There is something outside of Snowpiercer, though: us. As Ed Harris points out, near the end, “Curtis’ Revolution” is not a revolution, it’s a movie about a revolution, and as such, it displaces and suppresses real disorder (Nam and his daughter are the real free radicals, for him, because they are willing to blow up the train and take their chances with the bears.) But a movie about Curtis’ revolution is also not a revolution, and that’s what we’ve just watched: going to see Snowpiercer is escapist fantasy. It is the fantasy of escape we enjoy, but it might convince us that escape is an impossible fantasy if we make the mistake of taking the movie too seriously. But it's a movie.