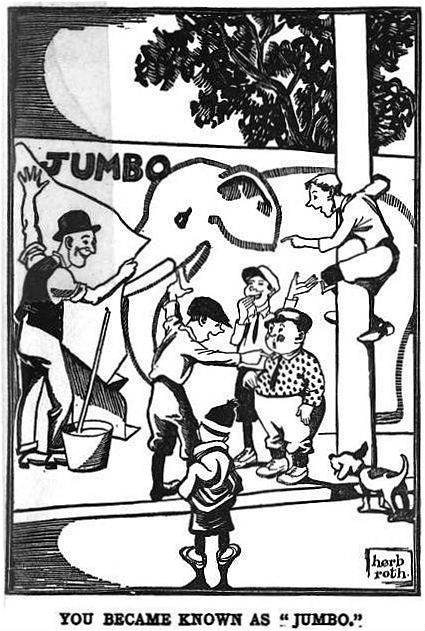

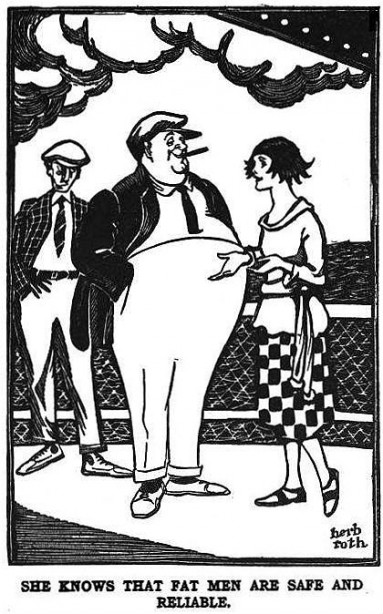

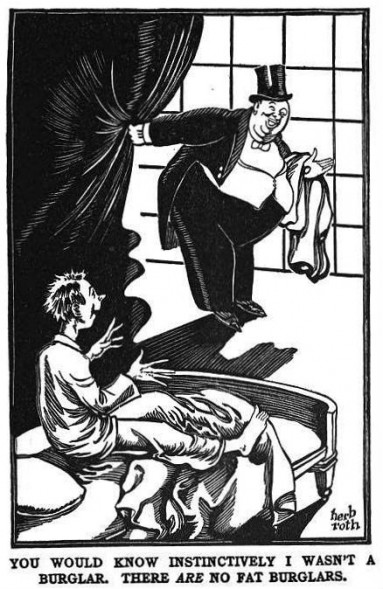

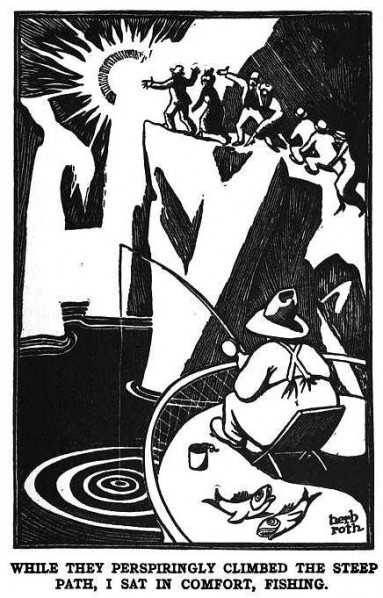

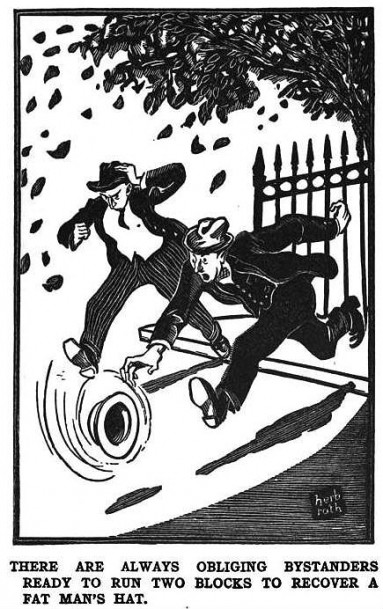

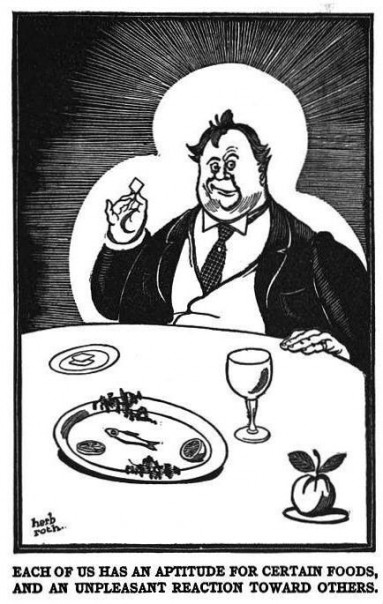

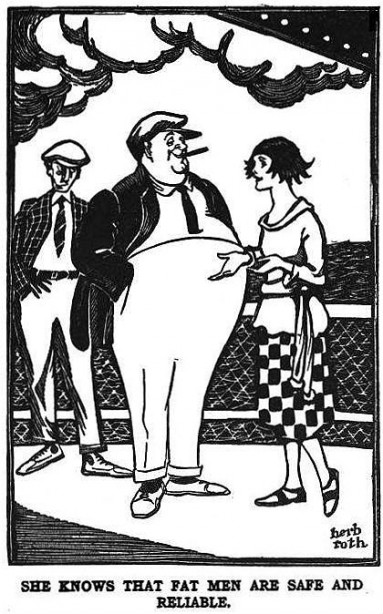

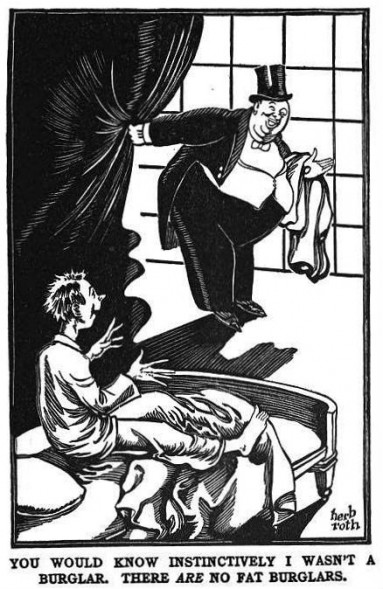

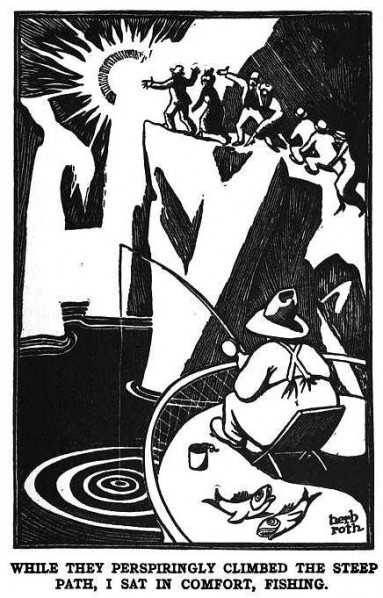

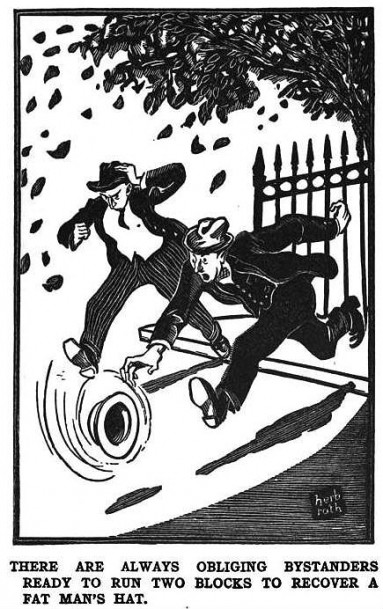

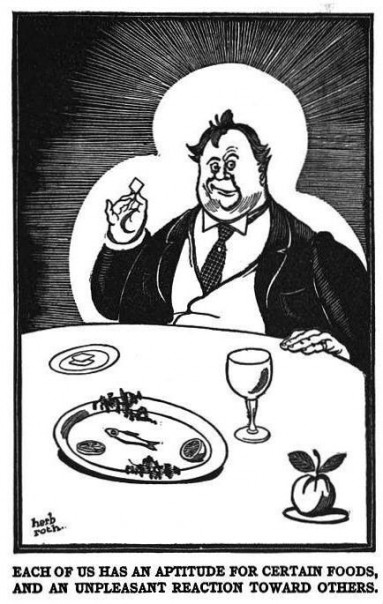

Illustrations from William Johnston's The Fun of Being a Fat Man (1922)

Percy Shelley subsisted almost exclusively on bread and water. A friend reported that the poet made sure his pockets "were generally well-stored with bread. A circle upon the carpet, clearly defined by an ample verge of crumbs, often marked the place where he had long sat at his studies."

We don't often hear of writers wrangling with their weight. But diet and fast they often did. Virginia Woolf never took a second helping. Fearful of his "morbid propensity to fatten," Byron subsisted on dry biscuits and soda water. Anaïs Nin merely nibbled. Franz Kafka

Kafka also drank large quantities of milk, which he considered essential for good health.

adopted the advice of nutritionist Horace Fletcher, who advised his followers to chew (one hundred times per minute, to be exact) their way to optimal health. Kafka lost so much weight from this routine that he remarked, "I am the thinnest person I have ever known."

More acutely aware of his dietary habits than most other writers, critic and novelist Vance Thompson published Eat and Grow Thin: The Mahdah Menus (1914), a slim volume inspired by his persistent dysmorphia. He felt ungainly, impotent even. His flab he attributed to living too much in the restaurants of the world, a habit that prevented him from living life at all.

"'You know I worship every pound of you, little woman,' says Watty, still coaxing. 'Why can't you trust me? You know, Dolly, darling, I wouldn't take your weight in gold for you.' And he tells her they never was but once in all his life he has so much as turned his head to look at another woman, and that was by way of a plutonic admiration, and no flirting intended, he says.... And that other woman, he says, was plump too, for he wouldn't never look at none but a plump woman.'" -- Don Marquis, Danny's Own Story (1912)

Thompson considered fatness life's greatest tragedy. "One could write books, plays, poems on the subject," he observes in

Eat and Grow Thin. It claims countless people

"There is a strange kinship between obesity and financial crime -- almost all embezzlers are fat," writes Thompson.

of talent and promise. Celebrated society belles "have vanished forever, drowned in an ocean of turbulence and tallow." Comely actresses who "filled one's soul with shining dreams" have since found themselves "wrecked on huge promontories" of their own flesh. Portly statesmen "cumber the earth, now mere teeth and stomach, as though God had created them ... only to show to what extent the human skin can be stretched without breaking." Indeed, Thompson invites readers to shudder along with him at the prospect of a "fat death" that follows descent into a "sebaceous sea."

No man more exemplified this sorry surrender to obesity than did the writer G.K. Chesterton. Thompson thought him one of the more pathetic types of fat men: one who forfends against others' laughter by being first to laugh at himself; one who jokes about wearing his maiden aunt's bracelet for a ring, who clowns, who slaps himself and wags a droll, sausage-like forefinger in his own piggy face. Such a man as this seems happiness incarnate, but he is truly one enormous mass of unremittent woe. "[I]f one should sink a shaft down to his heart -- or drive a tunnel through to it," Thompson writes in reference to Chesterton, "one would discover that it is a sad heart, black with melancholy."

"A diet consisting primarily of rice leads to the use of opium and narcotics," writes Friedrich Nietzsche, "just as a diet consisting primarily of potatoes leads to the use of liquor."

Though his ridiculousness constantly occupies him, it becomes even more acutely manifest whenever he falls in love. Romantic gestures become grotesquely magnified. The Chestertonesque lover "cannot kneel at Beauty's

"I didn't see any difference between a monarch butterfly and a viceroy," admits Vladimir Nabokov. "The taste of both was vile.... They tasted like almonds and perhaps a green cheese combination."

feet without a derrick to let him down," insists Thompson. "He cannot clasp the dear girl to his heart -- for fear of smothering her." His laughter and levity cannot mask the "tragedy in suet" that his life has become.

"Eating cherries today in front of the mirror I saw my idiotic face," wrote Bertolt Brecht in his diary. "Those self-contained black bullets disappearing down my mouth made it look looser, more lascivious and contradictory than ever."

Few ways for a graceful exit present themselves to the tragic fat man. He can, as Thompson points out, "drug out" the offensive excess or "boil out a great deal of his fat in a Russian bath." Yet either strategy produces a less than satisfactory outcome; though the fat might sluice from a man "like melted butter from a colander," the methods are as dangerous as the results short-lived.

"The accumulation of fat shortens life, causes disease and is in itself a disease since it is an abnormal and inefficient condition of the body," writes Eugene Christain in Weight-control the Basis of Health (1919). "What then we may ask was nature's purpose in giving us the power to lessen the length and efficiency of our lives?"

Lasting and safe results follow only from the Mahdah method. Reportedly as old as the writings of Galen, it allows dieters to dine well -- and wisely -- by virtue of its basis in sound science. "To the scientist," Thompson writes, "there is nothing so tragic on earth as the sight of a fat man eating a potato." Carbonaceous foods pile on the weight. To counteract such folly the Mahdah diet prescribes the exact foods required not only for reducing fat but also for regenerating "healthy tissue and ... strengthening of the whole body." Which foods benefit dieters most depends on the season. Summer's menu features more vegetables and fruit, while winter's showcases "heat-producing foods."

"Health without money is half an ague." -- George Herbert

Yet like every such plan, the success of Thompson's Mahdah diet hinges on abstention. It permits no alcohol consumption and banishes from dinner plates gravied meats, macaroni, butter, cheese, dried beans, rice, cereals, pork, milk, pastries, puddings, sweets, potatoes and bread -- all foods that purportedly turn the body into a fat-production factory. Prohibitions go beyond the strictly dietary to include other areas of life susceptible to overindulgence. At his readers Thompson directs the following injunctions:

Don't sleep too much.

Don't take naps.

Don't overeat, even of lean dishes.

Don't eat unless you are hungry.

Don't drink with your meals.

Don't take a cab -- WALK.

Dedicated Mahdah dieters could expect to lose two to three pounds a week. They would not only become thin but would "build up the tissues" as well.

"Fat men and women are popular because they are inclined to be liberal," writes William Johnston, "liberal in their thought, liberal in their opinions, liberal with their time, liberal with their money, liberal in regard to other people's shortcomings. Old King Solomon had them sized up right twenty-five hundred years ago. 'The liberal soul shall be made fat' was how he put it, and it is just as true now as it was then."

Fairly cosmopolitan if spartan, Thompson's Mahdah recipes include such exotic dishes as dolmas, Turkish mutton and Polish-style veal. A typical breakfast consists of coffee and fresh, ripe fruit, and a typical lunch by broiled lobster, cold fowl, stuffed eggs and sliced oranges. Dinner features an exciting medley of clam cocktail, fish, venison steak, french beans and grapefruit salad. On green vegetables dieters may snack whenever they take the notion.

The Diet Dressing, from Eat and Grow Thin: "Two tablespoonfuls vinegar. A pinch of salt and paprika. One-quarter teaspoonful mustard (dry). One teaspoonful of chives chopped fine or parsley. One teaspoonful tomato catsup or, if preferred, Walnut or Worcestershire sauce. Rub the salad bowl with an onion or with garlic, mix the salt, paprika, and mustard together. Add the vinegar, catsup and chives and pour over the salad. A finely shopped hard-boiled egg may be used from time to time."

Thompson guarantees that the Mahdah menu will make overweight folks happy, even if they must always guard against the return of their weight. "This natural, simple method of curing obesity," he writes, "has brought health and happiness to hundreds of the corpulent." This multitude did not include Chesterton, who perhaps showed himself wiser than his fellow writer when he observed that, though "certain great changes in habit or manner, in diet or discipline of life, would make practically all men good and happy ... the man who happens to know that nearly every one of these diets and disciplines has already existed somewhere" understands that "it did not prevent people from being as naughty or silly as they chose." Only a man whose life enacts a tragedy in suet recognizes the comedy implicit in many a fad diet.