I’ve been thinking about how the most tedious “authenticity” debates are the ones demanding that writers be Africans, or whatever authentic thing they must be; I’ve been thinking about how such demands put the burden on the writer, because what’s really going on is an effort to tell writers what they can and can’t write; I’ve been thinking about how rarely we ask someone to read Africanishly, and how silly it sounds when we do.

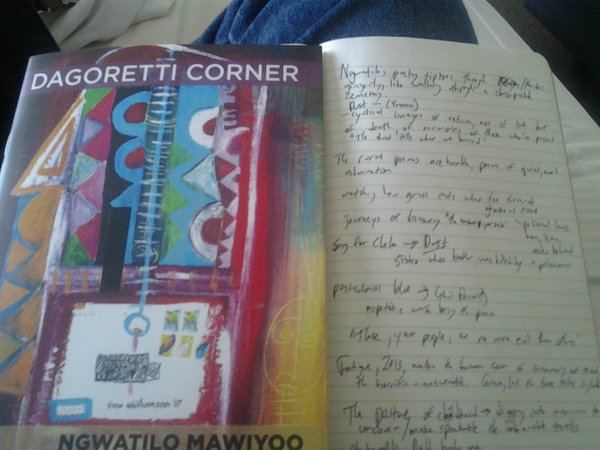

The more interesting question is: how to read this book of poems, what helps, how to help?

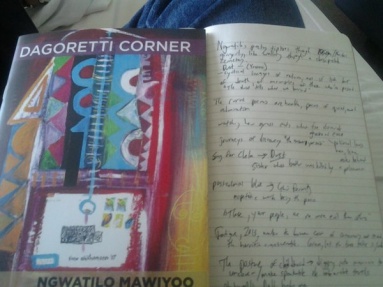

I don’t know if it helps to read Africanishly. It helps that I met Ngwatilo, once, and we had doughnuts and coffee in a weird Vancouver doughnuts-and-coffee shop that she suggested (she made this google-map walking directions thing for me to find it; I think I had a maple syrup doughnut, because of Canada). It helps that we talked about a lot of normal things, but also she told me about traveling through Kenya, how she had intended to visit 20 different families, in 20 different parts of Kenya, over 200 days (though she “only” made it to “7 different parts of Kenya in 70 days”).

It helps to know the grand intimacy of this project’s ambition, and it helps to explain why “twice in ten days” she took a mug of milk from a mother’s hand, “for my bones,” and why she wrote a poem about that:

It helps to know how close to the bone poetry can cut, that along with all the images of rebirth and baptisms that we find in this book—with all the rich symbolic overtones and metaphors—there’s also the miracle of opening yourself to the world and being given a mug of milk, for your bones.

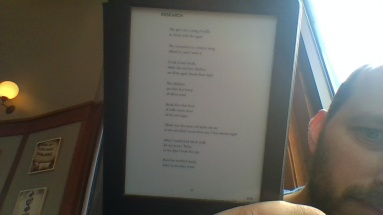

There’s something equally miraculous about this poetry, too, that you don’t need my help, if you have the courage to travel to where it lives, and be open to it; you can read something as small as Ngwatilo’s small book, and be left breathless and deafened by it without knowing anything about anything. The miracle of poetry is that it actually is, that a “book of poems”—words that train us to turn away, to give way (I don’t read poetry, who reads poetry, yikes, poetry voice, oh yeah, I don’t read much poetry, poetry sucks, oh I love poetry, haven’t read it in years)—turns out to be something as simple and breathtaking and real as this:

I don’t know how Ngwatilo wrote that, because I’ve never written poetry; but so many words must have been carved from the pages and pages of prose that thought would have eaten up if I’d written it.

This poem works. This poem helps.

A photographs works because of all that gets carved away, everything outside the frame, in time and space. And so with this poem: it’s such a fragile, perfect, simple expression of a fragile, perfect, and simple moment. Photography makes tangible something which is too tenuous for certainty: how to be sure what a parent is thinking? Their body is not yours, even if it once was. And though you can’t be sure, you can guess that your body might survive theirs, that you might have to choose a picture for their funeral program; the uncertainty of death is what death is, and the certainty of a photograph—the sameness of that image, which will never age, nor fade, nor die—is a snapshot of a moment, carved out of time, that time sweeps away from you, like a parent: he has almost died so many times. He has always lived, until he won’t, and until those snapshots of time becomes suddenly, permanently, tragically, precious.

The young learn to share other things than mangos, of course.

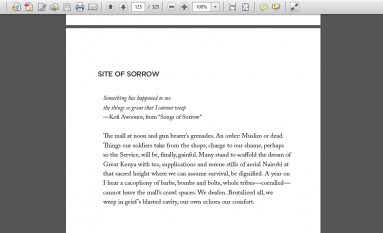

Her devastating “Site of Sorrow,” which I only dare to share in its entirety, carves something gentle, shared, and small out of the moment in time and space that silenced a poet, along with a sense of a nation; if we were to read Kenyanishly, I think we would know how rhythmically the Westgate bombing that silenced Storymoja still echoes. There is a violence in the way a Westgate poem is obligatory, as Keguro puts it, that a glimpse of Great Kenya from an aerial, sacred height—a bomb that corrals whole tribes in crawl spaces—became so deafening, making a poet’s voice impossible to hear.

But after silence, always, an echo. Deafened, but pounding a drum—and if I can read Swahilishly, I’ll note that an ngoma is a drum that’s also a song—there is something in Ngwatilo’s words that helps, that works, and most of all, that teaches you how to share. How else would we learn?