It's not so strange to compare avant-garde artists to social media users. They both produce a lot of content that few people bother to look at. And some commentators might be inclined to regard early adopters of social-media apps as avant-garde consumers, seizing on new possibilities for gratification, evasion, and status distinction. (Be like André Breton and install Secret on your iPhone 5S!)

In The Weak Universalism Boris Groys offers a somewhat counterintuitive definition of "avant garde" — one that is the opposite of "making it new." Since novelty is the status quo of consumer culture, the avant-garde seeks to advance from that, Groys claims; they must challenge and change the disposition of perpetual change.

This is a bit self-defeating. Groys argues that avant-garde artists, to evade this, aspire to make work that is "weak," in the sense of not being contingent, timely. Instead avant-garde artists try to reduce art to its transcendent, essential core. Because avant-garde work, in Groys's view, is committed to timeless purity, it can garner none of the popularity of mass art, which is rooted in the novel. And it is seen as undemocratic, even though it tries to bring art back to first principles. Shouldn't art that can be dismissed as something a child could make be regarded as ultra-democratic? Groys writes:

Avant-garde art today remains unpopular by default, even when exhibited in major museums ... the avant-garde is rejected—or, rather, overlooked—by wider, democratic audiences precisely for being a democratic art; the avant-garde is not popular because it is democratic. And if the avant-garde were popular, it would be non-democratic.

Groys wants to argue that what is popular is actually in fact elitist, since not all things achieve the same degree of fame. And since avant-garde art is unpopular, it allows ordinary people to see themselves as artists as well, making their own basic, unpopular work.

Indeed, the avant-garde opens a way for an average person to understand himself or herself as an artist—to enter the field of art as a producer of weak, poor, only partially visible images. But an average person is by definition not popular—only stars, celebrities, and exceptional and famous personalities can be popular. Popular art is made for a population consisting of spectators. Avant-garde art is made for a population consisting of artists.

Mass taste is then secretly elitist taste, because you are rooting against the underdogs by liking it. And there is nothing democratic, either, in broadly shared taste for something that is popular. Fascist leaders are popular too.

I am interested in this as it relates to vicarious participation (as opposed to "genuine" participatory art) and the current vogue for virality. It may be that we ordinary "nonartists" are not envious of the avant-garde but trapped within it, and we look to vicarious participation in popular art and virality to escape this curse.

If Groys is right, avant-garde art is at once universal (reduced to its elemental gestures) and only relevant to small local communities; if it were popular, it would become part of a historical zeitgeist and become doomed to be dated. This seems to me analogous to a certain fantasy about the purity of local music scenes and making DIY bedroom/garage music as opposed to the supposed fleeting insubstantiality of enjoying hyped superstars and corporate pop. Think of a million amateur bands playing the same elemental garage music in a million basements, and that is Groys's avant-garde. Such music not in any way original and doesn't aspire to be; it instead reiterates the timeless gesture of wanting to make music.

Insular collectives of artists or writers or even just friends on social media provide another analogue. They all consume each other's work as peers and have narrow enough horizons to ignore the ways in which what they are all doing might be considered derivative. Artists and audiences are one and the same in such circles; making and consuming are simultaneous, and hierarchies among participants are suppressed.

But at the same time, those fabled anonymous garage bands are inspired not merely by the impulse to make music but by the vicarious desire to become like the popular musicians they admire. Amateur garage bands wanted to be like the Beatles or, later, like the Ramones. They wanted vicarious participation in the notoriety of their idols. In their emulation of "popular art" they remain spectators, despite the way in which they contribute to, in Groys's sense, rendering that art "avant-garde" — they clumsily make it simple, generic, crudely timeless through inept imitation.

So it may be that popular, zeitgeisty mass art is necessary as a sort of timeless inspiration for the trickled-down creative impulse that yields basic, transcendent gestures of art making. If it didn't exist, we would have to collectively create it through a spontaneous coordination of attention to make what someone is doing appear to be the model for garnering social recognition, to make emulating it worth attempting. The spectator may need an impetus to become an artist capable of consuming/creating avant-garde art as Groys defines it. Groys suggests that "participatory practice" — starting your own garage band, or your own mosh pit, at least — "means that one can become a spectator only when one has already become an artist."

But one might go further and say we are born artists and find making art boring, childish, regressive, pointless, and we long for exposure to the kind of work that will turn us into spectators. This in turn would make it worthwhile to use our inborn art ability. If we're always already artists, then what vicariousness and virality offer is a chance to transcend that for something bigger — participation not in the banal routines of self-expression but in something genuinely larger than ourselves, historical.

Social media, as Groys suggests, makes users "avant-garde" to the degree that they try to use it to be "creative" in the sense of expressing themselves in the most generic of ways. Groys argues:

This repetitive and at the same time futile gesture [of making reductive avant-garde art] opens a space that seems to me to be one of the most mysterious spaces of our contemporary democracy—social networks like Facebook, MySpace, YouTube, Second Life, and Twitter, which offer global populations the opportunity to post their photos, videos, and texts in a way that cannot be distinguished from any other conceptualist or post-conceptualist artwork. In a sense, then, this is a space that was initially opened by the radical, neo-avant-garde, conceptual art of the 1960–1970s. Without the artistic reductions effectuated by these artists, the emergence of the aesthetics of these social networks would be impossible, and they could not be opened to a mass democratic public to the same degree.

That seems preposterous. I've been willing to argue that self-construction on social media is a kind of democratized performance art, but to claim that Facebook users couldn't do what they do if it weren't for actual late 20th century conceptual artists seems absurd. Only some infinitesimal percentage of social-media users would have had any exposure to such work, and even this small group may not have found the encounter particularly emboldening. And Facebook's engineers weren't exactly sitting down with Lucy Lippard's Six Years before coding new features for the site. The aesthetics of Facebook, Instagram, etc., have much more to do with what is built into the interfaces to generate circulation and interaction; these enticements don't seem to be necessarily influenced by conceptual art. If anything, it's more that both conceptual art and interface design owe something to cybernetics, network analysis, and postwar computer science.

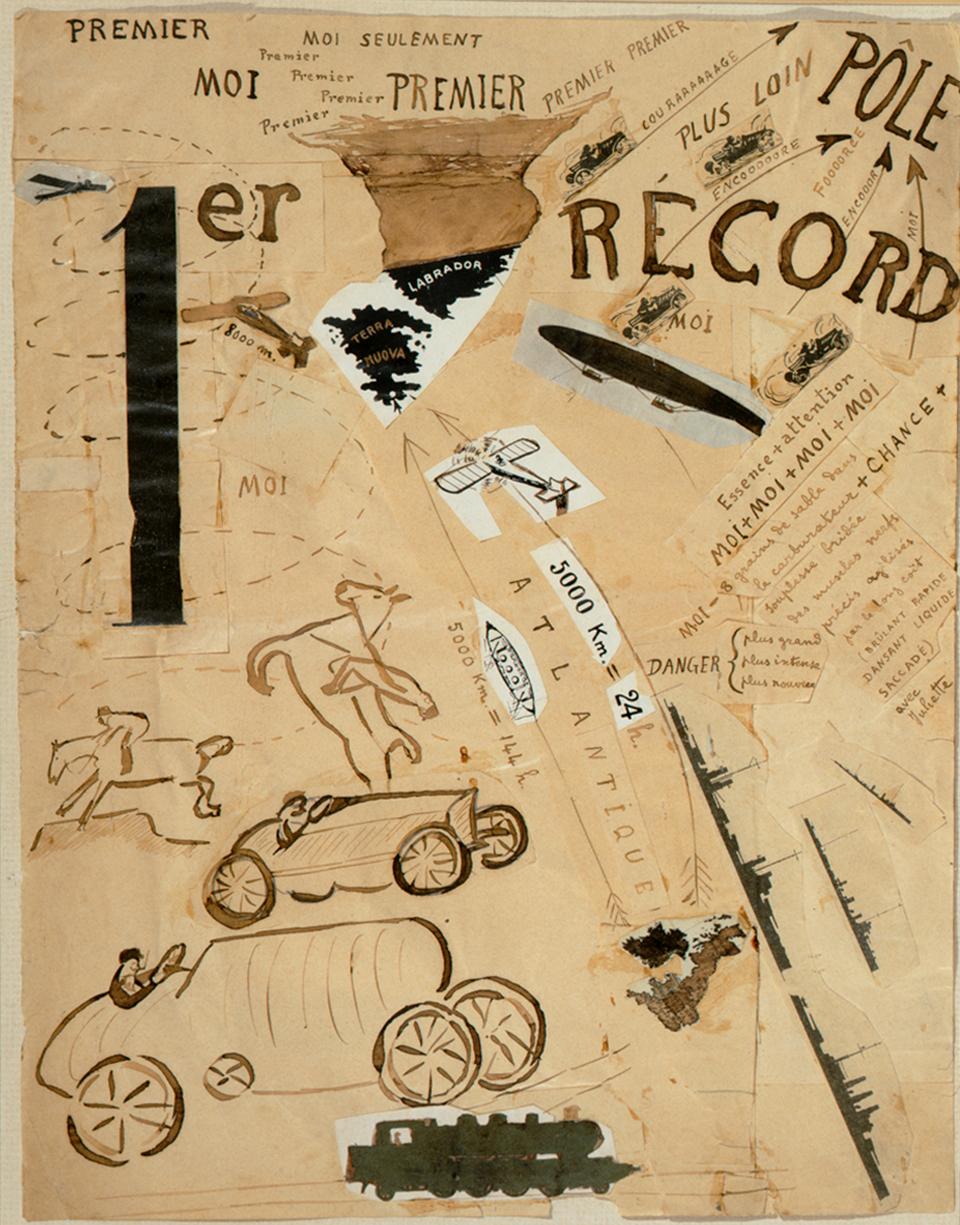

What I think Groys is talking about is the democratization of the expressive gesture that social media affords in its generic, preformatted fashion. It's similar to what Julian Stallabrass's list of the routine subjects of amateur photography, circa 1996: "Landscapes, holiday destinations, loved ones and pets, fragments of the urban scene and natural wonders all come to participate in a continuum in which all objects are known and (when things go well) all respond kindly to the photographer's subjectivity." The social media user is like the sun at the center of this universe of benevolent, displayable things. Like an avant-garde reductivist, the social-media sharer breaks down photography to its basic impulse of archiving and possessing. Every instance of social-media sharing is thus a potential repetition of Groys's avant-garde "weak gesture." It's a reiteration of Malevich's black square — "an even more radical reduction of the image to a pure relationship between image and frame," Groys explains, "between contemplated object and field of contemplation, between one and zero ... We cannot escape the black square—whatever image we see is simultaneously the black square."

Groys offers the dubious analysis that on social media too many people are sharing too many things and no one could possibly consume it all. (False: That's what algorithms are for!) This makes it unseen or even unseeable art, akin to Warhol's Empire. The point isn't to watch it; the point is simply that it exists as a limit. It is, in a sense, antiviral. It sits there, inert.

But the content of sharing on social media is not always "weak" in Groys's sense — it is not all timeless mundanity (photos of domesticity, pictures of meals, etc.). Much of it is an attempt to seem timely, to mark one's participation in successive waves of hype. It's writing about very specific things, like, say, House of Cards (to the intense irritation of those who aren't watching). Often social-media sharing is an attempt to belong to one's time and show how one is willing to change with it, not transcend it/be out of touch with it in a narcissistic bubble. We may know that everything that becomes popular is just a trend — that it is only "ready to disappear," as Groys says — but that can make it more, not less, urgent and exciting to participate in it.

This is what pursuing virality as a feeling is about. Groys is right that on social media "the facticity of seeing and reading" a particular piece of content "becomes irrelevant," but that is because its circulation and metastasis is being so carefully tracked. Virality is an aesthetics for ubiquitous surveillance. It takes being seen for granted and moves beyond that to momentum, circulation. In some ways, the concept of "curation" is too static for this era. One wants to put something out there that develops momentum, that has an unpredictable life span, that offers a vicarious gateway to the unbounded vitality of collective culture, which our solitary interfaces and devices tend to curtail phenomenologically. We try to get stuff (whatever stuff, it doesn't matter) to go viral to participate in that shared social enthusiasm that surges and dissipates.

The popular, then, is akin to the pre-individual, in Simondon's sense — a cultural matrix out of which our individuality emerges, its precondition. The avant-garde is the denial of that origin, embracing the mundane inevitability of individuation as some unique personal triumph.

Groys argues that once upon a time we were "expected to compete for public attention." That seems backward. Once we took for granted a certain recognition of our place and worked to transcend that, to dissolve into something anonymous, urban, genuinely "mass" — the level at which dreams of cosmopolitanism and universal legibility are conceivable. People wanted to escape local attention and vicariously enjoy fame — indulge in the fantasy of ubiquity without surrendering identity the way genuinely famous people must, usually to their psychic destruction.

We want vicarious participation in the popular because it feels less lonely than reclaiming one's inherent potentiality as a solitary, transcendent avant-garde artist. If everyone can be an artist, no one needs to be congratulated or recognized for being one. Instead, one needs to be recognized for the rarer skill of appreciation, of being able to sympathize with others and unite with them in feeling. Eternity is very lonely.