What are the words you do not yet have?

—Audre Lorde

No. Can’t write it out. Not now.

—Samuel Delany

Richard Bruce Nugent was the most famous . . . of the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” considered the first . . . of the Harlem Renaissance. The story opens,

He wanted to do something. . . to write or draw . . . or something . . . but it was so comfortable just to lay there on the bed . . . his shoes off . . . and think . . . think of everything . . . short disconnected thoughts . . . to wonder . . . to remember . . . to think and smoke . . . why wasn’t he worried that he had no money . . . he had had five cents . . . but he had been hungry . . . he was hungry and still . . . all he wanted to do was . . . lay there comfortably smoking . . . think . . . wishing he were writing . . . or drawing . . . or something . . . something about the things he felt and thought . . . but what did he think . . .

Publishing history has it that when Nugent first wrote the story, it had varying numbers of dots, meant to indicate different lengths of silence. One imagines they also symbolized different types of silence.

An editor—I suspect it was his co-conspirator Wallace Thurman—changed all the varying dots to ellipses.

*

Literary critic Mieke Bal points out that ellipses have no temporal limit: we do not know how long they remain silent.

*

The time of the ellipsis extends beyond duration—how long it lasts—and gathers multi-temporalities. Context tethers but does not restrict: the flashback preceding an ellipsis need not locate that ellipsis in the past. In fact, no rule provides that ellipses occupy a single and stable time.

An ellipsis consists of a space-dot-space-dot-space-dot-space.

Each dot and space potentially represents a different time, and a different duration to that time. Consider the following examples: a short past, a truncated future, a syncopated past, a conditional future, a long present, a subjunctive present, a black future. I have chosen temporal vernaculars. To these three, we could add subjunctive time, dream time, mythic time, conditional time, seasonal time, speculative time, and black time.

I lack the math skills to map the different possible combinations of past, present, and future as both spaces and dots.

These multi-temporalities make it possible to extend Nugent’s story in multiple dimensions.

*

He wanted to do something . . .

*

A savvy reader will point out that “black . . . gay” never appears in “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” although “black” occurs in different formations.

“his hair had turned jet black and glossy and silky”; “hair black and straight”; “to wear a long black cape”; “lie there in a yellow silk shirt and black velvet trousers”; “a field of blue smoke and black poppies and red calla lilies”; “among black poppies and red calla lilies”; “his hair curly and black and all tousled”; “a black poppy”; “the black eyes with lights in them”; “the forehead and straight cut black hair”; “a black-poppy stem”; “and black poppies”; “black poppies”; “Beauty’s hair was so black and curly”; “and the night was black”; “Beauty’s hair was so black”

*

To the charge that I am overreading Nugent’s work, I say yes.

I follow David Kazanjian’s lead:

Let me, then, make a case here for what is often called overreading. The charge of overreading is one I have long heard made by American historians and historicist literary scholars. On its face, the charge typically means that the overreader has attributed a meaning to a text that would have been impossible for the context in which the text was written or for the people who wrote the text. The charge also suggests that over- readers have an inadequate knowledge of history, that they have improperly assigned contemporary meanings to a noncontemporary text, that their perspective is unduly clouded by contemporary presuppositions. But what of the presuppositions of the charge itself, which is typically made with the kind of pragmatic confidence and institutional authority that requires presumption? The charge of overreading presumes a strict separation between historically contextualized reading and ahistorical reading, which in turn presumes that one can adequately determine the context in which a text was written and linger in that context with the text in a kind of epistemic intimacy. That is, the charge presumes that one can read as if one inhabited the same historical scene as the text one is reading; in this sense, as a kind of time travel, the charge of over- reading belongs in the genre of science fiction or speculative fiction. And yet it could never be of that genre, because its very presuppositions and claims are nonspeculative; the reading it claims not to overdo offers itself as sensible and moderate, as realist rather than speculative. I do not want to stop historicists from offering their speculative fiction as if it were realist; I learn much from that work and actually could not have even raised the kinds of questions I am trying to raise about my archives without it. But I do suggest that we also learn to read for the scenes of speculation in the archives we recover. (“Scenes of Speculation,” Social Text 125 [December 2015])

*

Ellipses are tethered to, but not restricted by, the words that precede and follow them. To write “black . . . gay” is to embed oneself within the afterlife of slavery. Saidiya Hartman writes, “This is the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment" (Lose Your Mother).

In a word, truncation.

The afterlife of slavery haunts “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade.” Consider this sequence:

he remembered how his mother had awakened him one night . . . ages ago . . . six years ago . . . Alex . . . he had always wondered at the strangeness of it . . . she had seemed so . . . so . . . so strange . . . yet . . . one’s mother didn’t say that . . . didn’t wake one at midnight every night to say . . . feel him . . . `put your hand on his head . . . then whisper with a catch in her voice . . . I’m afraid [. . .] yet it hadn’t seemed as it should have seemed . . . even when he had felt his father’s cool wet forehead . . . it hadn’t been tragic . . . or weird . . . not at all as one should feel when one’s father died . . . even his reply of . . yes he is dead . . . had been commonplace . . . hadn’t been dramatic . . . there had been no tears . . . no sobs . . . not even sorrow . . .

In the present of the story, Alex is nineteen. Alex’s father died when Alex was thirteen. I had misremembered the story as saying, “he died so young,” a sentiment that haunts the story. The story never explains how Alex’s father dies, but the ellipses figure the truncation that is the afterlife of slavery.

*

He wanted to do something . . .

*

I first encountered “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade” in the mid-1990s, in Go The Way Your Blood Beats, an anthology of black gay and lesbian writing. As with all gay and lesbian cultural production from that era, that anthology was produced within a calendar of loss, marked by the premature deaths of a still-emergent “black . . . gay” formation.

Dagmawi Woubshet writes, “Given the persistence of death in black life, black culture is imbued with an anticipatory sense of loss, recalibrating the calendar of mourning to record past and prospective losses in a single grammar of loss.” He adds, “Tallying loss is always an incomplete endeavor, especially tallying the loss of a catastrophe that is still unfolding,” in The Calendar of Loss: Race, Sexuality, and Mourning in the Early Era of AIDS (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015)

It seemed as soon as I encountered a work by a black gay author, I discovered the author had died from AIDS-related complications: Essex Hemphill, Marlon Riggs, Assoto Saint, Joseph Beam, Melvin Dixon. The books that marked the emergence of “black . . . gay”—In the Life, edited by Joseph Beam, Brother to Brother, conceptualised by Joseph Beam and completed by Essex Hemphill, Milking Black Bull, conceptualised and edited by Assoto Saint, Ceremonies, a collection of Hemphill’s prose and poetry, Love’s Instruments, a collection of Melvin Dixon’s poetry—were marked by repeated loss. I read Nugent’s story within this context of discovery and loss.

Nugent died in 1987, of old age, in the midst of the thousands lost to AIDS.

*

He wanted to do something . . .

*

Ellipses figure affective excess: they mark the place where language struggles to create, and fails.

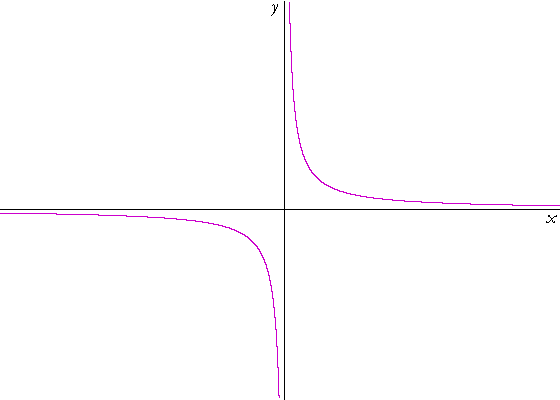

This place can be figured as the gap of the asymptote.

a straight line that continually approaches a given curve but does not meet it at any finite distance.

In one speculative model, one can leap across this gap—this is how Frederick Douglass the slave becomes Frederick Douglass the man. One can also speculate into this gap.

I am interested in the fissures of possibility created when those who fall or are pushed into that impossible gap are figured as representative. What can they represent, and how?

*

We get hints of this problem in Henry Louis Gates’s introduction to a volume of Nugent’s work, where he writes, “Bruce Nugent at last speaks here for himself.” Gates is famous for writing about representative figures who voice the black experience, so I read his comments about Nugent with unease. In speaking “for himself,” can Nugent speak for “the race”?

(I have no interest in designating Nugent a race man. I share Hazel Carby’s feminist critique of this hetero-masculinist figure.)

The problem of who Nugent can represent and how he can represent might fracture the frames through which one is considered representative. Such fractures—imagine a kaleidoscope—might multiply how representation can be thought and practiced.

*

*

Richard Bruce Nugent was born to a distinguished family in Washington, D.C. When he left home to move to New York to be a queer artist, his mother asked him to drop his last name so he would not shame his family. Richard Bruce Nugent became Richard Bruce.

Truncation.

*

This foundational “black . . . gay” story is engaged in wake work:

*

Wakes are processes; through them we think about the dead and about our relations to them; they are rituals through which to enact grief and memory. Wakes allow those among the living to mourn the passing of the dead through ritual; they are the watching of relatives and friends beside the body of the deceased from death to burial and the accompanying drinking, feasting, and other observances; a watching practiced as a religious observance. But wakes are also “the track left on the water’s surface by a ship; the disturbance caused by a body swimming, or one that is moved, in water; the air currents behind a body in flight; a region of disturbed flow; in the line of sight of (an observed object); and (something) in the line of recoil of (a gun)”; finally, wake also means being awake and, most importantly, consciousness.

—Christina Sharpe, “Black Studies: In the Wake,” The Black Scholar Vol 44, No. 2 (Summer 2014)

*

He wanted to do something . . .

*

“black . . . gay” attempts to name and inhabit the possibilities of the ellipses: to find a form for silence and language, to find a form for the unimaginable and the quotidian, and to risk thinking into the void.

*

He wanted to do something . . .

*

I linger at the desire “to do something . . . ,” to imagine into that opening a form of world-imagining that takes “black . . . gay” as its enabling fracture.