Bringing the greatest amount of happiness to the greatest number of people meant bringing greater misery to the already wretched

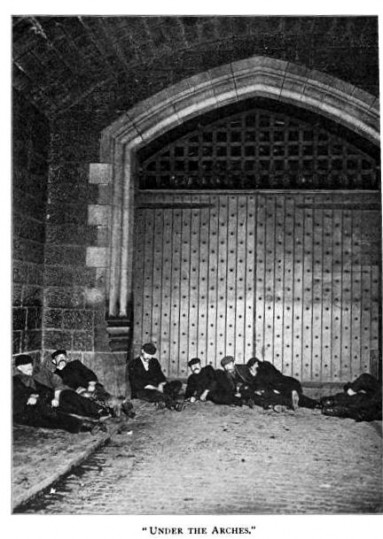

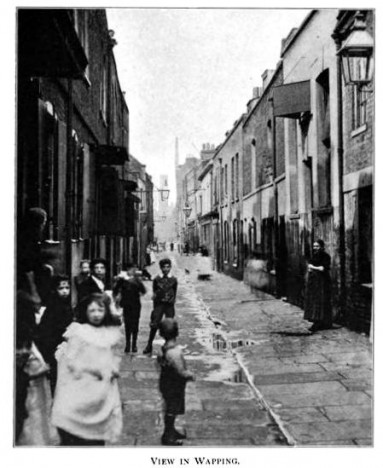

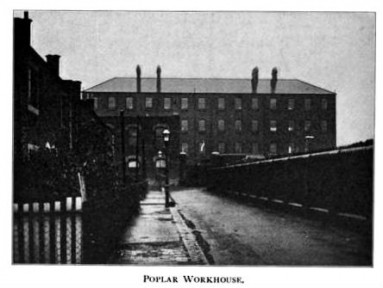

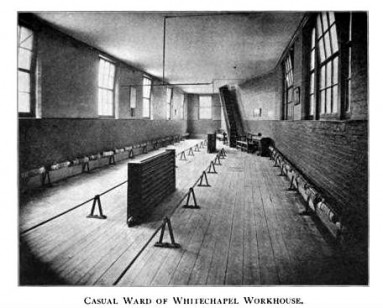

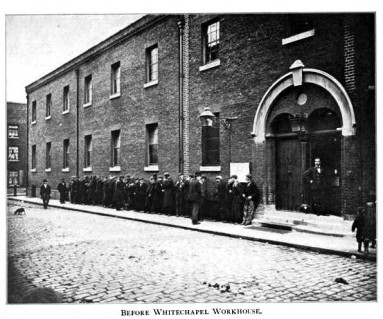

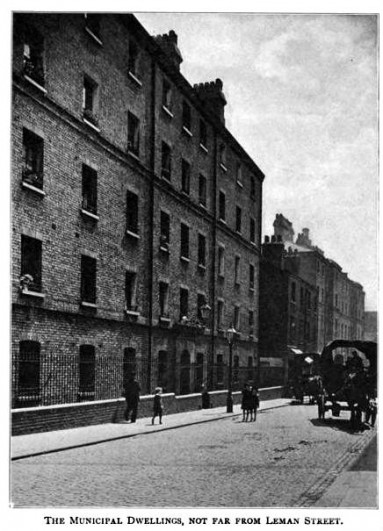

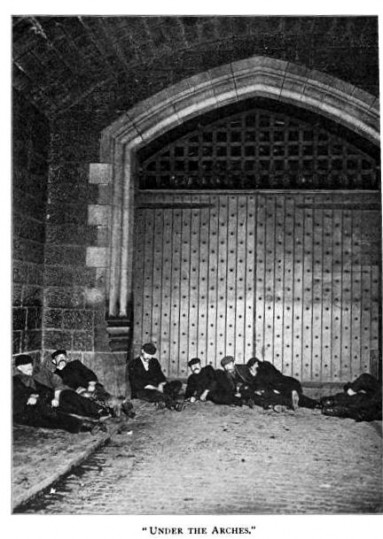

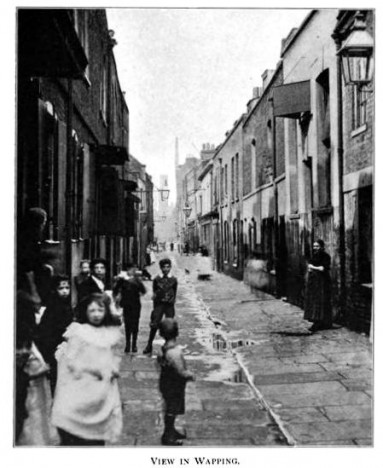

Photographs from Jack London's The People of the Abyss (1903)

"And I had rather seen an house of death, / Than those live men, unmanned, wasted, forlorn, / Looking toward death out of their empty lives." --Lionel Johnson, "In a Workhouse" (1889)

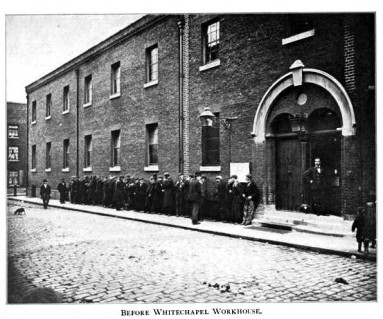

The indignities suffered by Joseph Merrick, who would later become known as the Elephant Man, were great and many, thanks to a rare affliction that left him bent, hobbled and covered with tumors and bony growths. Unfit for most work, the small jobs he did find came so seldom and paid so little that he could not support himself. His father nevertheless drove him from the family home into the streets of Leicester, where he wandered until he found the workhouse, the city's sole refuge. Behind its tall gray walls he lived for five years, his fellow residents the elderly, orphaned, destitute and infirm.

Daily workhouse schedule: 6:00, Rise. 6:30-7:00, Breakfast. 7:00-12:00, Work. 12:00-13:00, Dinner. 13:00-18:00, Work. 18:00-19:00, Supper. 20:00, Bedtime.

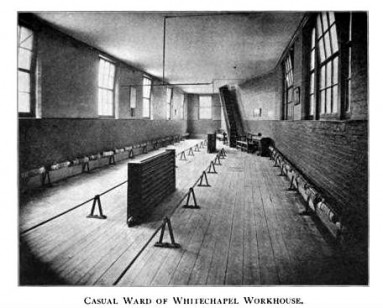

To these other inmates Merrick seldom spoke. He passed his days in silence, waking at dawn to the workhouse bell, rising from a small, spare bed, one of hundreds kept in a large dormitory, before making his way through dark corridors and drafty stairways to a room filled with old hemp rope, rags and animal bones. He was expected to pick apart the first two to make oakum, fibers to add to pitch for the purpose of caulking seams in ships' hulls. The bones he was to grind into fertilizer. For ten or twelve hours a day Merrick and his fellow inmates labored at these tasks. Evenings the workhouse master would gather their product and weigh it (a quota had always to be met) before extinguishing the gas lamps and locking the doors. At ten the final bell rang, signaling time for sleep.

In 1884 Merrick escaped by joining a sideshow. Yet he never forgot his time in the workhouse. In later years he would speak with loathing of those dull and dreary days.

The earliest known use of the term workhouse dates from 1631, in an account by the mayor of Abingdon reporting that "wee haue erected wthn our borough a workehouse to sett poore people to worke."

As dreary and dull as was Merrick's tenure, it was not at all uncommon. Life in Britain's workhouses was universally miserable, and deliberately so. The Poor Laws of 1834 prescribed unpleasantness as the best remedy for indigence. This remedy workhouses administered to perfection.

"At present, if a boy should feel a strong impulse upon him to learn the art of going aloft, he could only gratify it, I presume, as the men and women paupers gratify their aspirations after better board and lodging, by smashing as many workhouse windows as possible, and being promoted to prison." --Charles Dickens, "A Walk in a Workhouse" (1850)

So unpleasant were they that inmates committed crimes in hope of being transferred to prison, where conditions were somewhat better. Most, however, stayed put, whiling away the hours by breaking stones or, like Merrick, picking oakum. A stint in the workhouse was for them a fate worse than death, and often as unavoidable.

Not until the National Assistance Act of 1948 did the last vestiges of the Poor Law disappear, and with them the workhouses.

Such was the conclusion Friedrich Engels came to when in the 1840s he visited some of Britain's most notorious workhouses. Their inmates "were people beyond the pale of law," he wrote, "even beyond the pale of humanity." He saw sick men forced to work ten, twelve hours a day. He saw children menaced, women molested. He saw beds teeming with vermin. To this squalor was wed the most austere discipline. Inmates could neither smoke nor receive gifts from friends. They couldn't talk with relatives; fathers, mothers and children were all housed in separate wings.

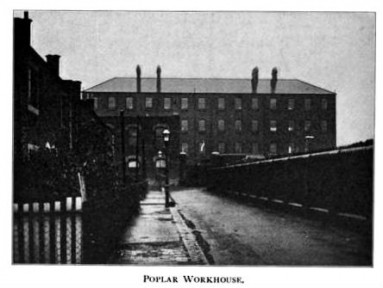

A popular workhouse layout was modeled after Jeremy Bentham's prison panopticon, a radial design with four three-story buildings at its center set within a rectangular courtyard, the perimeter of which was defined by a three-story entrance block and single-story outbuildings, all enclosed by a wall.

Glimpses of the world outside the workhouse were denied them. One workhouse, the Herne Common, was constructed in such a way that every window faced an inner court. "No wonder that they would die of starvation rather than let the door of the poor-law bastilles close behind them!," the young German could only exclaim in the face of these cruelties.

A government inquiry into conditions in the Andover workhouse in 1845 found that starving men and women were fighting over the bones they were supposed to be grinding, because they wanted to suck the marrow from them.

Even if they did let that door close behind them, workhouse inmates went hungry more often than not. They survived mostly on a farinaceous diet of potatoes, "very bad bread," (as Engels himself put it) gruel, thin soup and water. These foodstuffs workhouse administrators doled out with the strictest economy. Each inmate received his share, no more, no less (weights and measures on hand quashed any accusations of skimping)

The workhouse master and matron usually received six times the amount of food given to the paupers.

. The evening ration usually consisted of a pint of soup and six ounces of bread. Into this soup went three ounces of raw beef free from bone, two ounces of bone, two ounces of split peas, half an ounce of oatmeal, one ounce of vegetables, and a sprinkling of salt, pepper and herbs.

In terms of the quantity and quality of food offered, the workhouse menu could vary. One workhouse in Brighton was rumored more generous, its tables bearing meat in goodly portions twice a week. And one in London was notoriously stingier, its boards bearing nothing but gruel and water every day.

And the guardians and their ladies, / Although the wind is east, / Have come in their furs and wrappers. / To watch their charges feast; / To smile and be condescending, / Put pudding on pauper plates. / To be hosts at the workhouse banquet / They've paid for -- with the rates." --George R. Sims, "Christmas Day in the Workhouse" (1879)

The monotonous diet only experienced a hiatus on Christmas, when to great fanfare there appeared in place of soup and gruel roast beef and plum pudding, which came courtesy of workhouse patrons. Britain's elite donated each year a bit of their wealth to the feast, over which they presided wrapped in velvet and fur. With their own hands they served meat and pudding to inmates, likely delighting in the many "Thank'ee kindly mums!" which issued from the grateful paupers like so many prayers. But even this show of generosity was carefully measured, each serving of holiday cheer dished out in scant ten-ounce portions.

Why such meanness? Because the commissioners who oversaw the workhouses insisted that workers be kept working

"I felt I was embarked in a great cause.... My heart was in it." --George Nicholls, Poor Law Commissioner (c. 1834).

. Relief therefore should be so unbearable that, as one overseer put it, those seeking it would look to the workhouse "with dread," the "reproach for being an inmate of it" extending "downwards from father to son." Poverty commissioners saw as a plague, and their duty was to keep it from spreading. Should the shame and horrors of the workhouse make the pauper take a chance with starvation, so much the better. "If they would rather die," said Dickens's Ebenezer Scrooge of England's poor, "they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population."

"Receipt for a very cheap soup" from Essays, Political, Economical, and Philosophical (1802) by Benjamin Thompson (better known as "Count Rumford"): "Take of water eight gallons, and mixing with it 5 lb. of Barley-meal, boil it to the consistency of a thick jelly. -- Season it with salt, pepper, vinegar, sweet herbs, and four red herring, pounded in a mortar. -- Instead of bread, add to it 5 lb. of Indian Corn made into Samp, and stirring it together with a ladle, serve it up immediately in portions of 20 ounces."

"An imbalance between rich and poor is the oldest and most fatal ailment of all republics." --Plutarch

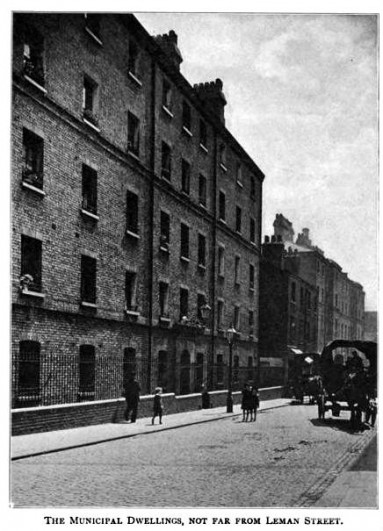

What wasn't really discussed was that even if father or son found work, he often couldn't wring enough earnings from that work to feed, clothe and shelter his family. "In some counties," a Select Committee on Labourer's Wages found, pay was so low that "to support a wife and child without parish assistance" proved impossible. Many workhouse inmates owed their poverty in part to the disappearance of well-paying jobs. These were replaced by those that paid low wages, provided only sporadic employment and preferred unskilled over skilled labor. Where there's a will there's a way, the commissioners likely reasoned. But as Joseph Merrick and countless others found out, that way was often barred to those who suffered the hard luck of being born poor.