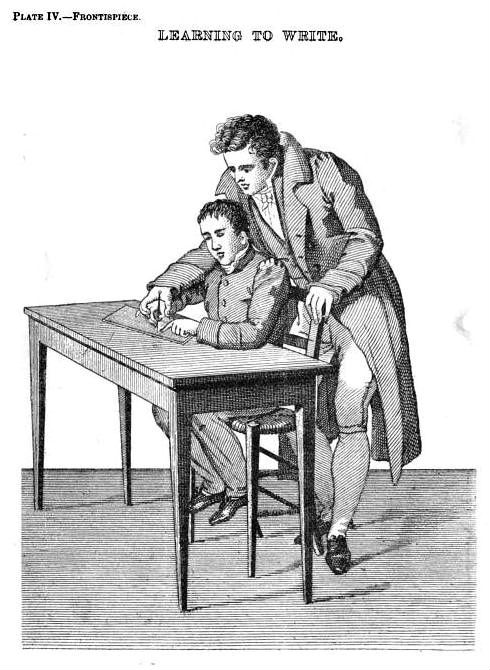

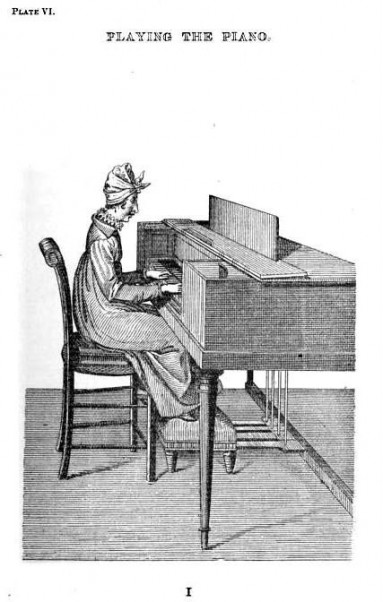

Illustrations from An Essay on the Instruction and Amusements of the Blind (1894)

Doonhamers (as the natives of Dumfries are called) marveled at the devotion and exactitude Tom Wilson displayed as he rang the mid-steeple bell of the town's belltower. The chief ringer, he braved winter freezes, summer storms and autumn deluges to discharge his duty three times daily, even on holidays, when other bell ringers hid under their bedclothes.

"To be blind is not miserable; not to be able to bear blindness, that is miserable." -- John Milton

The townspeople marveled because Wilson was blind. (He lost his sight from smallpox soon after his birth on May 6, 1750.) Yet this did not keep him from being one of the most generous and inventive residents of Dumfries. He knew the town by heart, and on a Saturday night could often be seen guiding drunk residents home. He assisted lost strangers and contrived clever board games to play with the town's other blind residents. Music enchanted him. He attended concerts and joined music societies. Often ringing through the concert hall could be heard his laugh, which the others in attendance generally forgave out of affection for their "Blind Tom," as they called him. He loved his king, too. On mad George's birthday, he would ascend the steeple, point his pistol heavenwards and fire several celebratory shots into the air.

"For nine-tenths even of seeing men, daily, customary, life is a dark and mean abode. Unless he often opens the door and windows, and looks out into a freer world beyond, the dust and cobwebs soon thicken over every entrance of light, and in the perfect gloom he forgets that beyond and above there is an open, boundless, air." -- John Sterling

"Blindness is a confinement, but also a liberation, a form of loneliness which propitiates inventions, a key and an algebra." -- Jorge Luis Borges

Those times when Blind Tom wasn't shepherding tipplers or raising hell with bells and pistols, he worked in his small, tidy house fashioning ingenious devices -- pails for brewing beer, tinsmith's mallets, huckster's stands. He even built a carriage to bear him on his journeys. His skill the townspeople esteemed; Blind Tom proved a darn sight better at using a lathe than did any of his fellow tradesmen.

"Oh! stranger do not pity me, / Nor pass me with a sigh, / Because the great and blessed light / Is hidden from mind eye; / What though I cannot see the orb -- / I feel the warm sun shine, / My mind has conjur'd up a world / As beautiful as thine." -- Joseph Edwards Carpenter, "Song of the Blind" (1841)

Blind Tom did much to cultivate his skill. He traveled for miles visiting workshops of talented tradesmen, handling their wares with care, picturing them in his mind and making note of their construction. He taught himself how to turn wood and made a decent living by it. Dumfries wives clamored for his spurtles (long wooden mixing utensils), which he made with ease. His tools he arranged along a wall in such a way as always to know which one he grabbed. Employing no assistant, he sharpened them himself.

"The ordinary food of the peasantry is oatmeal porridge and milk, when milk can be got, for breakfast; for dinner, potatoes and salt herrings, or other kinds of fish, -- and with the better economists, pork or bacon differently prepared; and potatoes and milk or herrings to supper. The bread is oatcakes or scones, composed of potatoes and oatmeal, or more rarely, of potatoes and wheaten or barley-flour." -- The New Statistical Account of Scotland: Dumfries, Kirkcudbright, Wigton (1845)

Blind Tom proved a deft hand in the kitchen, as well. He cooked from scratch using only garden-fresh ingredients. He grew and harvested his own potatoes (his row he could discover without fail among a hundred others), fetched his own water and even dug peat for the kitchen fire.

"In boilin' water, salted weel, / 'Tween fingers, rin the ruchsome meal, / While the brisk spurtle gars them wheel / In jaups an' rings-- / Ae guid half-hour, syne bowls may reel / Wi' food for kings. / Nae butter, syrups, sugar brown, / For him wha sups shall creesh thy crown, / But milk alane, maun isle thee roun', / Till thou dost soom, / Then a' he needs is ae lang spoon, / And elbow room." -- Robert Bird, "Scotch Porridge" (ca. 1890s)

Tom's wholesome cuisine kept him ringing his bell until his seventy-fourth year. As fate would often have it, the job he loved most claimed him. He was found one morning slumped next to his bell, having only hours before suffered a stroke. He died Scotland's oldest bell ringer.