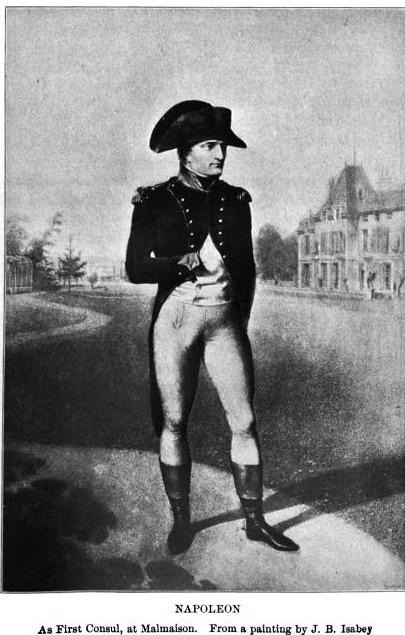

Picture from Thomas E. Watson's Napoleon: A Sketch of His Life, Character, Struggles, and Achievements (1915)

Snugs nooks outfitted with wall-length mirrors and chairs upholstered in red velvet shelter men and women, who chat as they sip from demitasses. A waitress in a white apron wipes her knife before slicing a cake into squares. Patrons pass in and out, quickly and lightly as moths. Business is in full swing at a café in the City of Lights.

The cosmopolitan leisure that the Parisian café has come to symbolize belies its humbler origin. The story of its emergence is written in blood and fire, namely, that which was spillled and ignited during the Napoleonic Wars. With the defeat of the Grand Armée at Waterloo in 1815, the French went from victors to vanquished, from occupiers to occupied. A stay-behind force of Russian soldiers made camp in the Place de la Concorde and under the trees shading the Tuileries and the Champs-Élysées. Undoubtedly flush with pride in having defeated the formidable Bonaparte, these troops enjoyed making their presence known, staging parades that the Parisians viewed with bitterness and envy. In battle, the Czar's soldiers fought doggedly. In barracks, they behaved impeccably. In victory, however, something of the "old Ivan" came over them; the city they regarded as theirs to plunder.

"After having used coffee with indifferent frequency and copiousness for many years my sight became abnormally weak," writes J.M. Holaday in "Coffee Drinking and Blindness" (1888), "and I began to feel a horror of darkness, wishing that the sun would never set, and desiring instinctively to go to some place where the nights would be short during the entire year."

Such was the Russians' lusty vigor that it achieved wide renown. An English nobleman visiting Paris set himself the task of discovering its source.

The English nobleman's investigations were reported by John William Cole in Russia and the Russians (1854)

He followed one soldier home to his billet, where he found numerous men, unclothed and looking, as he put it, "squalid and meagre." The good English peer conjectured that an inadequate diet explained their sorry state. He learned that a mere "twelve shillings per annum" were the wages the rank-and-file realized for defending Mother Russia, an amount that purchased little besides "coarse rye bread, fermented cabbage, and buckwheat grits." For drink they relied on

kvass, which they made by allowing sour bread to ferment in half a bucket of water.

"Bread is to the peasant a sacred thing, whilst the rich look down upon it with contempt. This difference in views is but the reflection of the thousand years' class rule"--"Das hungerude Russland," as quoted in the January 1, 1901 edition of Free Russia.

So rude and inadequate did Sir William find these provisions that he imagined that Russian troops must howl, "Hopdance cries in my belly for two white herrings!", as did poor Tom in

King Lear.

Picture from C.G. Hunter's Russia: Being A Complete Picture of That Empire (1817)

Sharp indeed their hunger pangs must have been, for they brooked no delays when it came to table service. On those occasions when the occupying Russians felt themselves flush enough to dine out, they did so with characteristic impatience. "

Bystro,

bystro!" ("Quickly, quickly!") they were known to shout after hapless wait staff. For all the Russians soldiers' apparent impecuniousness, their custom was as frequent as it was boisterous--frequent enough, at any rate, to have contributed to the French lexicon a synonym for "café."

From Receipts and Household Hints (1870): Café au Lait--The French are justly celebrated for this breakfast coffee, which may be made as follows: Use an infusion, made as directed, or in a cafetière, only of double the strength, and when clear, pour it into the breakfast cups, which have been previously half or three-quarters filled with boiling milk, sweetened with loaf sugar.

Russian soldiers also contributed something to the design of these establishments. Those sleek, shining zinc counters for which the bistro is known were first implemented during the occupation. The Russian troops were wont to bang their fists as they barked commands. Wine spilled as a result. Dreading the prospect of ruin, café owners began lining their counters with zinc, which stood up against messes and blows much better than did wood. And so it is that a place thought so quintessentially French is in fact the child of Russian ill-manners.

Later in the nineteenth century, Max Beerbohm would observe, "Mankind is divisible into two great classes: hosts and guests." The Parisian cafe proprietors doing business in the immediate aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars found themselves saddled with guests of the worst sort. A few years later the Russians left Paris--and the French were left holding the tab.