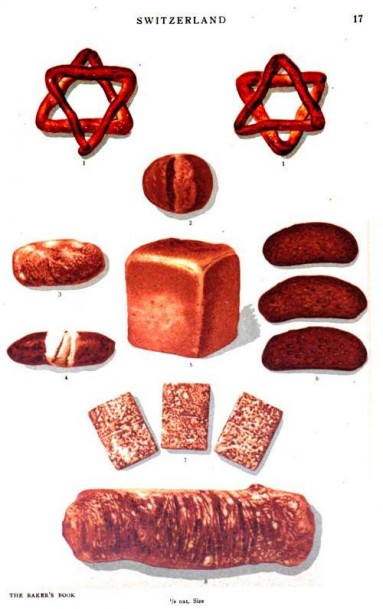

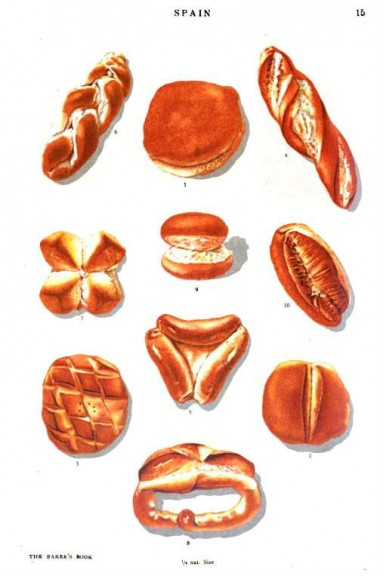

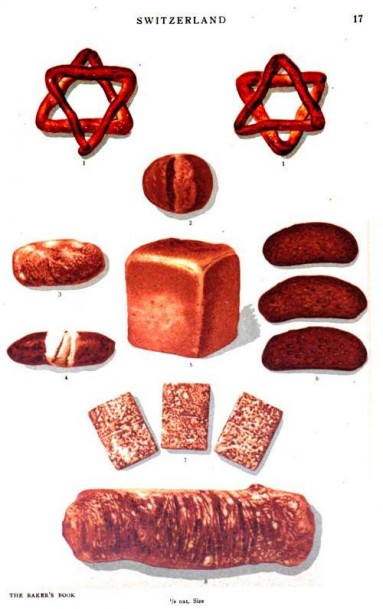

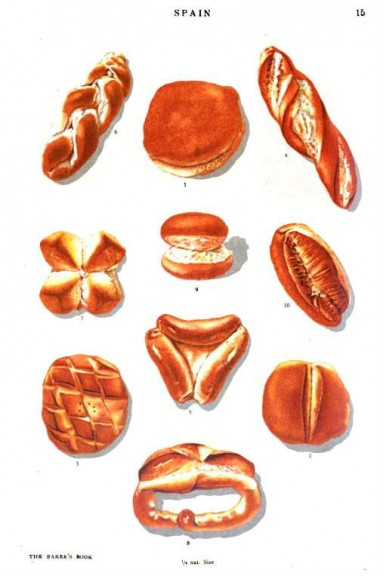

Illustrations from Emil Braun's The Baker's Book (1902)

An earlier version of this essay appears at The Austerity Kitchen’s old site.

Pass some dinner rolls their way and today's weight-obsessed gastronomes, ever mindful of carbohydrates and calories, will likely demur. Yet such reticence history shows to be unusual; the attitude prevailed for centuries that a meal without bread was no meal at all. Peasants, burghers, artisans, beggars -- each alike clamored for a crust to munch with their meat. Two to three pounds of bread the typical working-class Parisian would consume, the typical Spaniard even more. Any fruit or vegetables on their tables appeared as accents, barely more than condiments.

"The primitive Christians of the East, who retired from persecutions into the deserts of Arabia and Egypt, lived healthfully and cheerfully on twelve ounces of bread per day, with mere water," writes Sylvester Graham in A Defence of the Graham System of Living (1835). "With this diet, St. Anthony lived 105 years; James the Hermit, 104; Arsenius, 120; St. Epiphanius, 115; Simeon, the Stylite, 112; and Romauld, 120."

In Russia the host offers bread and salt to everyone who enters his house. His failing to do so indicates that the visitor is not welcome.

Monarchs demanded their mealtime loaf as well, and they made quite a show of eating it. A 1663 feast hosted by Transylvanian Prince Apafi Mihály, whose guests included an entire Ottoman army recently triumphant in battle, featured among other things two-score enormous boules. This show of starch so impressed the Turkish world traveler, Eviliya Celebi, that he remarked upon it in his journal. "The meadows were covered with Hungarian carpets," he wrote, "onto which forty giant loaves were placed." The prince's method of conveying the loaves to the hungry soldiers Celebi found equally impressive. "Each one had to be drawn on an oxcart," he continues, for "each ... was twenty paces long, and fives paces wide, and as high as a full-grown man."

Baking day did not lack its charm. Hungarian housewives usually kept in reserve a scrap of dough to bake at the front of the oven, close to the flame. This bread, called lángos, tasted faintly of smoke and was eaten with fresh herbs and cheese.

As tasty as they undoubtedly were, the prince’s burdensome boules faced stiff competition from his neighbors to the west. Another adventurer, writing some hundred years later, praised the bread of Hungary for its unsurpassed toothsomeness. "Nowhere else did I eat bread that was lighter, whiter, and tastier than this," he declared. Baking such bread was no easy feat. Only once a week could busy peasants manage the task: on Saturday for purpose of greeting the Sabbath with a fresh loaf. Kneading alone took a good two hours and required an ox's brawn and endurance. Left to rise overnight, the dough had to enter a hot oven before dawn the next morning. It was a doughty soul indeed who refused to let this chore dissuade her.

Reporting from an international bread exhibition, Mr. Pusch, the author of a renowned book on bread published around 1900, notes that a "Mr. Josef Rieger of Vienna" sent an extensive and most interesting collection of bread. Among them was "the Gschradi, a roll of about three ounces in weight" as well as the oddly named "Judas-Striezel" and a most excellently made prison bread. From Graz came "an assortment of fine breads including a species of wine biscuit," and from the city of Agram, in Croatia, came a working-class bread of maize flour that sold for two cents a pound. The highlight of the Austrian exhibition came from a native Bosnian, a Mr. Puska Ahmed Ago, who exhibited a "Harem bread." A detailed description of this last loaf Mr. Pusch has failed to record.

"A loaf of bread, a jug of wine, and thou." -- Omar Khayyam

And perhaps that soul loved her bread all the more for the work she put into it. No housewife dared neglect her bubbling pot of sourdough, her bread's leaven, that she had likely received from her mother, such being the tradition among Hungarian women. The starter she would have used to bake the first loaf for her husband, and every loaf thereafter. So dear were her loaves that only her mate could slice them. If a Catholic, he would mark them with the sign of the cross before taking up his knife. If during their portioning a piece fell to the floor, he promptly picked it up and kissed it in apology.

Pliny writes that the Roman armies on their return from Macedonia brought Grecian bakers into Italy. Before they did so, they prepared their grain in a kind of pap or soft pudding. Hence they were called "pap eaters."

If grain stores ever fell short -- as they often did for reasons of weather, war, inadequate transport or poor soil -- Hungarians, like their fellows in other countries, rioted. The uprising wrought tremendous devastation -- bakeries looted, government officials harried, merchants drawn and quartered. Observed Jacques Necker, an 18th-century French statesman and child of the Enlightenment: "The people will never listen to reason on the subject of dear bread."

Recipe for a "good rye bread" from Henriette Davidis's Praktisches Kochbuch für die gewöhnliche und feinere Küche (1897): "1 litre milk, which must be lukewarm. 6-8 pounds refined rye flour and 100 grams good yeast. The night before baking the bread mix the milk, some salt and half of the yeast with some of the rye flour into a thin dough. Let sit in a warm place overnight. The next day mix the dough with the rest of the flour and yeast, knead it thoroughly, and form into long loaves. Place in a heated oven and bake for two hours. Note: Mixing the dough the day before triggers the fermentation process, which is necessary for good bread."

The admittedly simple nature of bread prompts one to wonder why Hungarian peasants held this foodstuff so dear. Their ethnic cuisine certainly admitted of tastier things: great glistening haunches of roast pork; stews made with horse meat and onions and flavored with paprika; yogurt and honey; figs as fragrant as rose petals. But such dishes seldom appeared on the tables of the poor. The rich alone dined on them at will. A king might proudly display his wheaten loaves, but they did not represent his sole sustenance. That distinction fell to the peasant, who kneaded, baked and guarded each crumb with his life -- because to each his life he owed.