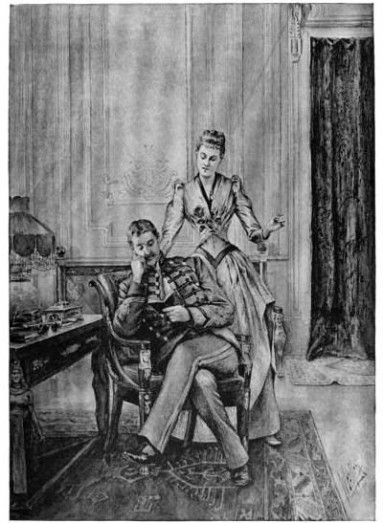

Illustrations from Ludovic Halévy's A Marriage for Love (1891)

Love rooted in frustration bears the sweetest fruit: This the old wives of New England knew. When on long winter nights a suitor called on an eligible daughter, her parents served him pie, bound both his legs in a large woolen sock, and bundled him into bed with his sweetheart.

"I dreamt about you last night -- fell out of bed twice!" -- Shelagh Delaney, A Taste of Honey (1958)

Under eiderdown the lovebirds canoodled until sunrise, when limbs again swung free to carry the swain on his way. If the night passed well, marriage banns would appear soon after. If it did not, the whole ritual repeated with another young man, should one happen by.

There is a delicious pleasure in clasping in your arms a woman who has done you a great deal of harm, who has disliked you for a long time and who is quite ready to dislike you again. Take the success of French officers in Spain in 1812." -- Stendhal, On Love (1822)

Many thought bundling strange. One prominent New York physician called it a "ridiculous and pernicious custom." Others blamed it for the precipitous decline in Yankee morals. But its defenders deemed it an economical and humane prelude to marriage. A couple bundled burnt no candles, they insisted, and other household members could rest easy knowing they had spared their visitor a tramp home in the winter night.

"In so far as we close our eyes to love and deny its law, we are the henchmen of death," observes Gilbert Cannan in Love (1914). "It is easier to drop a stone than to throw it into the air."

A visitor didn't need to have romance in mind to gain a berth. Lovers and strangers alike could count on the same reception. Passing peddlers, wandering huntsmen, itinerant poets, and even enemy soldiers all found a place to lay their head. During the Revolutionary War, a British officer faced the prospect of bundling one night in autumn. Lieutenant Anbury had marched all day. The sun had long since set, the moon yet to rise. He trudged along a road outside Williamstown, Massachusetts. Great ruts scored the roadbed, which had softened with rain, and his servant and the mare carrying his bedding had fallen behind.

Though Anbury yearned for sleep, he stopped to wait for his small retinue. They did not come. The cold and the dark urged him on. Soon he came to a modest cabin. He knocked at the door. A knobby old man, his wife and their young daughter answered. They bade him stay the night. Anbury had a quick eye, and saw only two beds in the one-room cabin. "Where am I to sleep?," he asked the mother. "Mr. Ensign, our Jonathan and I will sleep in this, and our Jemima and you shall sleep in that," she answered, pointing to the smaller of the two beds. "Our Jemima" was a buxom brunette of sixteen. The lieutenant blushed. "Oh la! Mr. Ensign," the father laughed, "you won't be the first man our Jemima has bundled with, will it Jemima?" The girl smiled, and winked at the reddening man. "No, father, not by many, but it will be with the first Britainer."

A recipe for wedding cake from The Young Housekeeper's Friend (1846): "Five pounds of flour, five of sugar, five of butter, six of raisins, twelve of currants, two of citron, fifty eggs, half a pint of wine, three ounces of nutmegs, three of cinnamon, one and a half of mace. Mix it like pound cake, only rub the fruit into the flour."

Memory of the event lingered with Anbury. "In this dilemma what could I do?," he later wrote. "The smiling invitation of pretty Jemima -- the eye, the lip, the -- Lord ha' mercy, where am I going to!" But the spirit proved stronger than the flesh; Anbury declined the invitation. How a man native to those parts could sleep chastely near such a toothsome creature as young Jemima this red-blooded Englishman could not fathom. He chalked it off to the "cold ... American constitution"; it alone, he surmised, could sustain this "unaccountable custom ... in hospitable repute, and perpetual practice."

Yet cold constitutions ensured the availability of warm beds. Suspicious of bundling to the end, the good doctor from New York insisted that the improbable chastity of the practice remained more perceived than real. Something managed to wriggle free of those straitjacketing body-socks, something from which sprang a "long-sided, raw-boned, hardy race of whoreson whalers, wood-cutters, fishermen, and peddlers" who in a great and hearty multitude populated windswept Nantucket, Piscataway and Cape Cod.