The life and loves of one Victorian butterfly enthusiast go to show how hard it is for a lepidopterist to change her spots.

An illustration from Fr. Berge's Schmetterlings-Buch (1889)

Men were like butterflies to Margaret Fountaine: They were apt to flit away without warning or leave-taking. Either creature she nevertheless pursued with vigor, and she recorded her experiences in thick leather-bound diaries she took with her everywhere. They contained accounts of her bicycle trip through France and her motorcar excursion across Tenerife, which she made with eight young Spaniards. In Corsica she took up with a gang of bandits before sailing for Cuba and Chile. Her many affairs

"Butterflies mate by day on the wing," reports a 1900 issue of School Education. "Both sexes of a species are in search of the same kind of flowers to supply their food, and so they meet."

she characterized as "so many gates leading on, through paths of sorrow, to ultimate disaster and final loss." This sense of disappointment attached only to her wingless loves, however. For the other kind her affection went undiminished. No distance proved too great or journey too perilous to divide her from them.

Around the turn of the last century Fountaine sailed to Crete, where she hoped to find the elusive Lycaena psylorita, said to be one of the rarest butterflies in Europe

From John Fowles's novel, The Collector (1963): "I dreamed myself collecting pictures, having a big house with famous pictures hanging on the walls, and people coming to see them.... But I knew all the time it was silly; I'd never collect anything but butterflies."

. The rarity of this insect owed to the fact that it made its home in the treacherous Psiloritis Mountains. She enlisted the help of a courier and a muleteer, and together they ventured forth. The circumstances of her alpine trek were anything but comfortable. Never before had she "ridden over such infamously rough tracks." Twice her horse slipped, and once it almost pitched her over a cliff. The stumbling, bumbling beast did its worst, but its rider managed to escape without a scratch.

A recipe for poached eggs from Vegetarian Diet and Dishes (1917): "Choose very fresh eggs. Three-quarters fill with water a saucepan that is not too deep; put in a little salt and vinegar. When the water begins to boil, break the eggs into it one after another, with great care and as close to the water as possible; so that the eggs do not fall too far, nor the yolk break."

Fountaine hunted her quarry relentlessly, stopping only to rest and eat. For such meals and amenities as were available high in the Psiloritis she relied on locals. A cloister at Sabatiana served her a luncheon of bread and poached eggs, which she ate with gusto. But the night's stay also offered her she accepted with decidedly less pleasure. "I never pass a night in a Greek monastery without having good cause to regret that I am not an hemipterist," she remarked, apparently sorry that her passion for insects did not extend to the kind of bugs her cell crawled with.

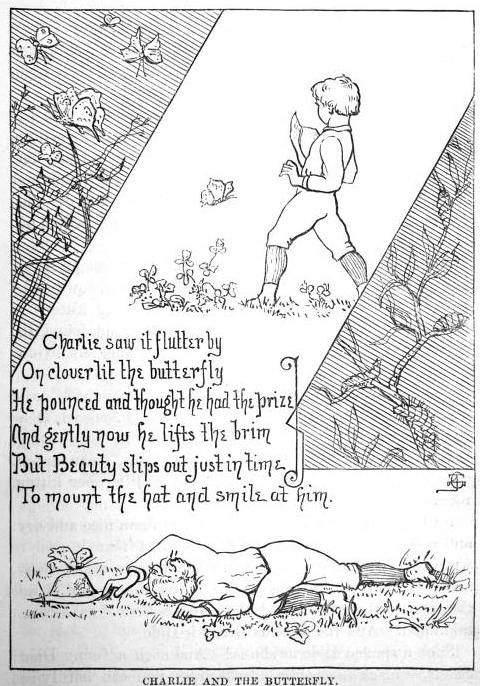

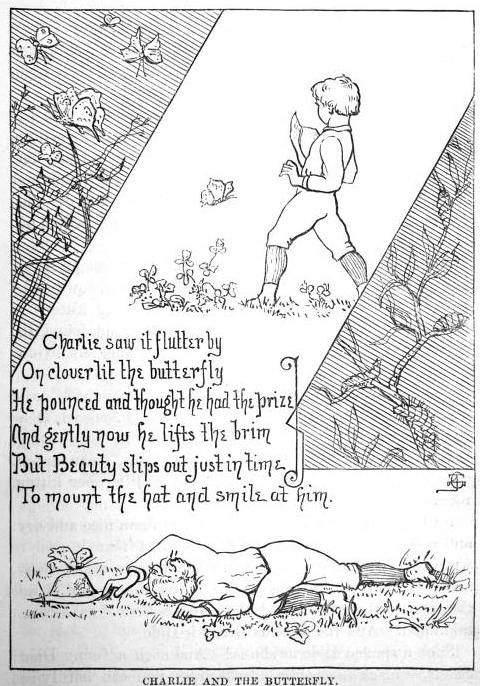

An illustration from an 1878 issue of The Nursery

Release from the bug-infested monastery brought no comfort. Mountain life is a hard life for ascetic and layperson alike

"It is not surprising that the ancients should have seen in the butterfly, emerging winged, beautiful, from the lowly earth-bound chrysalis, a symbol of the human soul," writes Margaret Warner Morley in Life and Love (1920). "The Greek word 'psyche' means both soul and butterfly. And in Greek mythology we find the beautiful maiden Psyche, the personified and deified soul, often represented with the wings of a butterfly."

. Fountaine discovered this during her stay with some shepherds. The cream cheese they served her, though "quite delicious," did little to distract her from "the squalid appearance" of their village. "I could not but wonder how it was that perpetually living in such ennobling scenes does not elevate the minds of these people," she complained. "Their dirt and squalor was something incredible, and I was indeed glad when the moment arrived for me to mount the little grey mule and ride away."

Gladness swelled to ecstasy when Fountaine caught site of her first live Lycaena. It hovered and darted above a watering hole that led to a deep gorge. It was small, dun-colored, hardly more than a moth. This "certain little brown butterfly," she insisted, "though of most insignificant and trifling appearance to the eye," nonetheless represented "a prize worth getting." As the muleteer and courier grimaced with exhaustion and chagrin, she charged forward, swinging her net this way and that, catching as many butterflies as she could while minding the drop or the odd sheep.

"There is no difficulty in killing so delicate an insect as a butterfly," argues Edward Routledge in Routledge's Every Boy's Manual (1869). "Some of the larger-bodied moths have the strongest objection to die, and if you pinch them, or cut them asunder, or stamp upon them, they still persist in living. But a butterfly is killed easily enough, and the only difficulty is to know how to kill it without damaging the rich and fragile plumage of the wings."

Satisfied that she had captured specimens enough, she deftly chloroformed them and stowed them for transport.

Her mission accomplished, she returned to the village where she had earlier stayed. Perhaps as a result of her triumph, it had become utterly transformed in her eyes. In place of the formerly poky little settlement she saw a charming hamlet "in one of the most beautiful situations I have ever seen." Whether the shepherds compelled once again to play host to their peculiar guest regarded their situation the same way, the reader is left to wonder. Suffice it to say that were she to have suddenly flitted away, no one would have pursued her.