There are plenty of aspects of women's magazines that may be cause for earnest concern. The most visible of these is, of course, the whole skinny models/airbrushing thing. By "visible" I mean exactly that: It's a phenomenon observed with the eyes, making its supposed fallout—dissatisfaction with one's own non-professional, non-retouched appearance—seem somehow more important, more visceral, than whatever our more intellectual quibblings might bring to the fore.

But for my $4.99, the larger problem is one of tidiness. Something you hear time and time again in the office of a ladymag is the need for a "takeaway": What do we want the reader to take away from this piece? What value do we want her to derive from it? It's good editorship to keep the question of reader value foremost among one's concerns when developing any part of a magazine, of course, but what the term "takeaway" too often means is this: What hopelessly simple, tidy, boiled-down bit of wisdom/advice/how-to/glimmer of worldview can we offer readers? I'd like to think that's changing, and certainly some magazines are more guilty of this than others, but as I've written before, many of the problems of women's magazines are inherent in their structure, supported as it is by mainstream advertising. My wish for women's magazines has always been to find one that presents a mix of genuinely helpful service, thoughtful explorations of "women's" issues—including fashion and beauty—that goes beyond a feminism 101 take, and that has a sense of humor. Throw in some gorgeous photographs—preferably those that address the first problem outlined above, that of impossibly thin models—and lady, I'm there.

Enter Worn. The 10-year-old Canadian periodical refers to itself as a fashion journal—which, in its scope and depth, is accurate—but I prefer to think of it as the fashion magazine so many of us have longed for. A signature mix of practical information, fashion histories (the evolution of stewardess uniforms, the Frederick of Frederick's of Hollywood, Victorian—and contemporary—hair art), personal essays, and stunningly imaginative pictorials, Worn reads like a dinner party where the guests are smart but not smarmy and the food leaves you feeling truly sated.

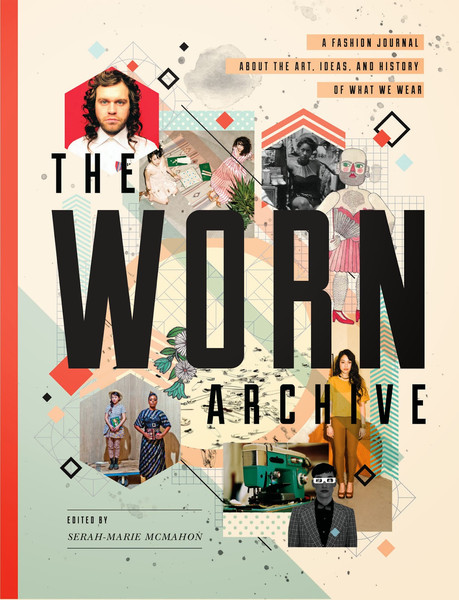

Which is to say, you should be subscribing. But for those who prefer to receive their reading in bulk, Worn has produced its first collection, The Worn Archive, anthologizing its first fourteen issues. True to its ethos that our wrappings can transform us into something simultaneously recognizable and utterly unique, the book, edited by Worn founder Serah-Marie McMahon, is more than a bound chronicle of those issues: Divided into thematic sections ("Fashion Is Personal," "Fashion Is Design," "Fashion Is Fun"), even the pieces regular Worn readers may have seen before take on a new meaning in the anthology. In "Fashion Is Object," for example, Worn walks us through that quintessential fashion object—the shoe, specifically the prototypical 1940s pump as well as the vast shoe archive of a collector—alongside a fashion history of the safety pin and an essay from a textile conservator. "Fashion Is Identity" sees a primer on various hijab styles and a story on how the pink-is-for-girls thing came about riding alongside a history of how gay men used fashion to signal one another. (On the 1970s "clone" look of gay men adopting conventionally masculine dress: "By dressing like 'real men,' clones had discovered that masculinity was a performance with costumes no less contrived than the fairy's tailored suits or the radical drag queen's gowns"—can you imagine this being written in a conventional ladymag?)

Not that, despite this critical complexity, the collection is short on reader service. You'll learn how to fashion a clothes line, make four classic tie knots, and whether you should dry-clean that vintage find, mostly bundled under the "Fashion Is Practical" section. Even there, tucked in amid service, creative intelligence abounds, particularly with a piece on what our culture lost when most of us stopped learning how to sew. Neither is the magazine short on sheer beauty—the photo shoots (which appear to feature what has come be termed as "real women," as opposed to professional models; I even caught some leg hair, shown not as a gender-rad fuck-you but as a part of what composes a woman's body...which I guess is a gender-rad fuck-you, in a way) are exquisite, and the articles are elegantly presented, with custom illustrations and photography, allowing the reader to consistently remember that fashion is a lived experience using all the senses, not only the intellect.

But back to the question of the "takeaway." It's a useful editorial idea—after all, you want your readers to take something away from your publication—but where so many mainstream magazines have gotten it wrong by thinking that the "takeaway" means something bite-sized and neat with no loose ends, The Worn Archive (available here, under editrix name Serah-Marie McMahon) gets it right, reveling in those loose ends, trusting its readers enough to take the information presented to them and come up with their own takeaways. Nearly every piece in the collection does this beautifully, but the one that particularly stands out is a riveting story about the "Beauty Is Duty" campaign, in which the British government worked with women's magazine editors to urge women nationwide to keep up their looks during WWII. It would be easy to either critique this as a low point of objectification of women, or to cheerlead it for its kitsch factor alone (after all, the piece is illustrated with a shampoo ad of a woman in curls juxtaposed with that same woman in a helmet, with the headline "Hair Beauty—Is a Duty, Too!"). Instead, Worn examines the phenomenon with its characteristic thoughtfulness, acknowledging the very real sense of stability that beauty routines can give us in the midst of national chaos while keeping in mind the consumerist, gender-bound ethos at the base of the campaign. It's stories like this where The Worn Archive shines the brightest—a feat that wouldn't be possible if the journal ever dared to underestimate its readers. Thankfully, it never does.