Though they were published in English out of order, the sequence of three novels that Yuri Herrera has sometimes called his “border trilogy” adds depth and complexity as it goes along. Signs Preceding the End of the World—his second-written, but first-translated—is a masterpiece, a journey into the underworld that is also a voyage of rebirth, noir fiction that’s also cosmological millenarianism, excavating the Mexica afterlife. The Transmigration of Bodies—his third written, second-translated—concerns the flows and circulations of social life and death, and the work done by bodies to keep the streams going (as well as the work done to bury them when they stop). You could say that in both novels, he is fascinated by death, but that just lifts the lid of how he turns noir conventions into something much richer and more ancient-feeling; because his work lives in the in-between spaces, the walls built by bodies and the bodies built by walls, death becomes the very stuff of life, and the deeper you go, the deeper it gets.

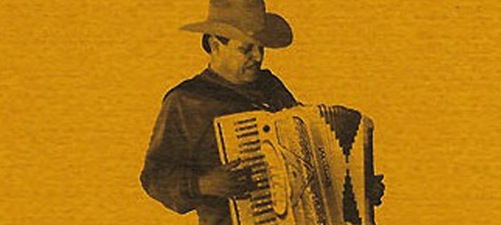

Compared to those two novels, I’ll confess that Kingdom Cons--translated, as ever, by the great Lisa Dillman--felt almost straightforward. The plot is comparatively easy to summarize: a youth—penniless and without family, but a talented singer—catches the eye of a great man, a King, who gives him a place in his household as court musician. From there, a rather predictable sequence of events unfold: our protagonist is dazzled, and then he is delighted; in the inevitable third act conclusion, he is disillusioned and the house comes down. As the various retainers and hangers-on are absorbed into their function in the King’s household, they lose their name and become, simply, the Jeweler, the Manager, the Doctor, the Heir, the Gringo, the Commoner, and so on; our protagonist, introduced as Lobo, becomes “The Artist” as he joins the top dog’s pack, gladly submerging his identity into the glamor of the crown.

As an anatomy of sovereignty—and of art’s relationship to power—the structure allows the reader to discover, with the protagonist, the work that makes a king: literally entitled Trabajos del Reino—“Works of the Kingdom”—Herrera’s political science background shows through in the parable he’s constructed about patronage networks. The English title emphasizes the protagonist’s discovery that his art is fiction—that it is hymns which make the God, and Cons that make the Kingdom—but the tension between work and con is where the novel lives, the ways fantasies of power become the real thing, or better. It’s therefore the boy’s innocence more than his talent that makes him fit for the work: because he believes so intensely in power—because it is almost literally all he knows—his corridos do their work and build the kingdom… until he is disillusioned, and they don’t.

It’s been a strange thing to read these three novels in this order. If you were hoping that Kingdom would be another Signs or Transmigration, it is and isn’t. Herrera’s prose style is astonishingly consistent, magnificently simple and concise and yet somehow so precise that he might as well have carved his novels in stone; Kingdom Cons shares with the later novels their startling economy of plot, and the vertiginous sense of hidden depth. You can read these slim novels in a sitting, but they don’t feel like “novellas” in any diminutive sense. They feel old, ageless, outside of time. But for all Kingdom Cons’ deconstruction of the form, it is still, fundamentally, a corrido-novel, a narco-novela; it is a bildungsroman about socialization and alienation, and a fish-out-of-water who explores the aquarium. It’s the sort of story that we’ve read before and which we’ll probably read again.

Part of what makes the later novels feel old is the work of reconstructing dead genres into new ones—something I wrote about here—but there’s none of that here. Kingdom Cons starts from a much fresher place: instead of being burdened by old stories, worn down by cynicism and loss, the young protagonist of this novel starts from scratch. And so, this story about making something out of yourself when before you were nothing, the story of social birth and innocence—and of the pup first weening himself—becomes a vastly more interesting novel, when you can anticipate the novels that will come out of it. Collectively, they form a sequence from birth to death, and what might scan as a relatively simple genre novel on its own—and what might have been exactly that when it was written, over a decade ago—now carries the weight of what hadn’t yet happened, but now seems like it always would have, as the artist grows and matures.