An article in a recent issue of the Economist details the tobacco industry’s troubles around the world with maintaining the value of its “intellectual property”: brand names, logos, package designs, and advertising aura. Governments have apparently recognized that tobacco companies have “the best pricing power of any industry,” as a consultant cited in the article somewhat euphemistically put it — that is, their customers are literally addicted to their product and will probably buy it if it came packaged in dog vomit. Given that the companies have that sort of leverage, states are acting to take away their brand power, mandating plain packaging and banning various forms of advertising. “The design of the box is where they must convey not only the name of the brand but abstract qualities, such as masculinity or the idea that a product is ‘premium,’ and worth an extra outlay,” the article explains. “If such traits are stripped from packs, consumers may choose cheaper brands.” But won't those smokers fail to taste the magic in the more expensive nicotine itself?

The article also points out that the industry has described anti-advertising initiatives as “expropriation of intellectual property” — theft of the immaterial value added to tobacco products over and above whatever intrinsic value they have through advertising and design. Tobacco, seen from this vantage point, is just a (toxic, unfortunately) medium for conveying ideas and social values in a compelling, visceral way. It is just another form of media that we get addicted to.

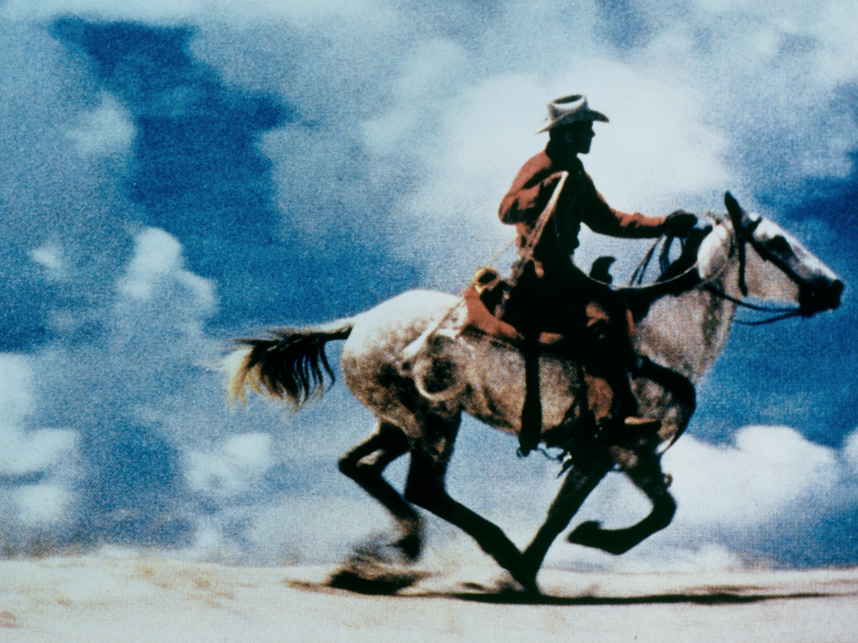

A cigarette is a cigarette is a cigarette, and when a smoker chooses one brand over another, they are in the realm of pure ideology. They have bought into the idea of the cigarette as a medium, which maybe isn’t physiologically addictive but can be a hard habit to break nonetheless. Ideology is addictive. It feels good to consume an idea like, say, “masculinity” as so much smoke you blow out of your mouth. It functions like a tautological argument: I can’t explain in logical terms why the Marlboro makes me feel more manly, but I can feel something indisputable happening in my lungs. It is reassuring to feel why you believe something on the bodily level, even if that feeling is ultimately associated arbitrarily with what it represents for you.

Governments, then, are trying to turn tobacco from a medium back into a generic substance again. They want to strip tobacco down to its core compulsive essence so that smokers must face that they smoke because they are nicotine addicts, not because they are brand loyalists, or because they like the message the cigarette medium can convey: that they are young or rebellious or sexy or sophisticated or cool or whatever other abstract idea companies have managed to associate with smoking. Rather than regulate the messages cigarettes communicate, the government is trying to make cigarettes noncommunicative by censoring the messages packaged around them, as if people won't think to feel anything about smoking if the discourse around it is somehow stripped of all allusiveness. As if then they will just be addicted to smoking qua smoking or, even more abstract, addicted to the state of being addicted.

This seems an unlikely outcome. It seems more plausible that addiction generates its own rationalizations, its own myths, its own ideology. We need to experience a physical grounding for our ideological beliefs, and we need to have ideological excuses for our physical addictions, so they tend to work in tandem, symbiotically. The compulsion to smoke drives a quest for ideological rationalizations ("smoking is cool"), just as the need for belief drives the quest for compulsive, physically affective practices that seem uncontestably "real." Compulsion authenticates practices and the ideas associated with them; it removes incentives and calculations from the equation. You do and feel and believe because you have to, altogether. At a certain point it seems inconceivable that I decided to smoke; the taste for what smoking represents to me no longer seems optional, a conniving ploy at something, either. It feels reflexive, like a craving.

Brands can seem like a way to add a phony value to an otherwise undifferentiated commodity. But they also mark the entry point for consumers into some vicarious fantasy, some idea tangential to consumption. The potential value of a brand rests in the conflation of compulsion and the desire to believe. It must make you feel as though you are choosing and also have no choice.

When governments mandate that cigarette packaging must be ugly, it may be that smokers' ideas of beauty will change. There is no reference point for beauty that compulsion can't shift, no absolute ugliness that can anchor a sense of repulsion where we once felt compelled. A substance makes us compulsive and we put that compulsion to use to make something else, some idea of ourselves, feel desperately necessary, mandatory, inescapable. We'll create a brand-shaped hole wherever we project our compulsions.

So it seems doubtful to me that a government can take a thing that has functioned as a medium, as a vehicle for wishes and fears and fantasies, and nullify it simply by making it plain. The smallest differences can be made to signify. Our desire to enjoy brands is probably stronger even than the desire to smoke. We can't suppress the yearning to have a specific name for the things we love.