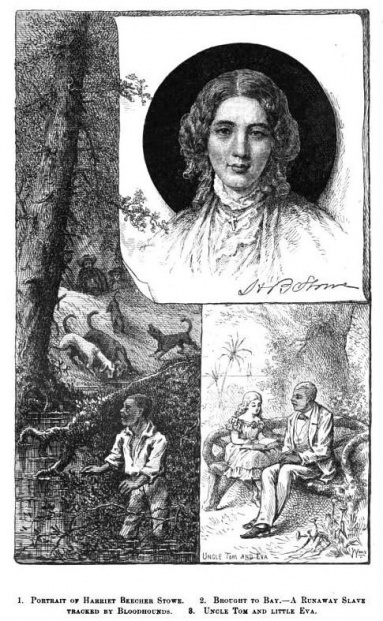

Illustrations from Our Famous Women: An Authorized and Complete Record of the Lives and Deeds of Eminent Women of Our Times. Giving for the First Time the Life History of Women Who Have Won Their Way from Poverty and Obscurity to Fame and Glory (1888)

Socialism in one country may be a difficult undertaking, but socialism in many American country towns was as easy as pie — and just as appetizing

"The only thing that will redeem mankind is cooperation." --Bertrand Russell

My schedule having become busier, making dinner is now a chore. Before, I’d found a certain serenity in chopping carrots and slicing tomatoes after a day of brainwork. Now, vegetables oppress me, especially as my CSA share has been unusually full of late. Against them I mobilize food processor and pressure cooker. Yet these implements must be hauled from the cupboard, assembled, disassembled, and cleaned. Then there’s the cooking, eating, and cleaning up.

"Housekeeping ain't no joke." —Louisa May Alcott

Of course, this problem has a ready solution. I could simply surrender to meals shrink-wrapped and microwavable. But I doubt I’m capable of it, believing as I do in the idea that, as Art Buchwald put it, dinner is "not what you do in the evening before something else. Dinner is the evening."

What’s a commuter to do?

For more on cooperative kitchens, see Dolores Hayden's The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities (1981)

Like so many of today’s “first-world problems,” a solution had been in place years ago and later abandoned. In 1868, Cambridge, Massachusetts housewife Melusina Fay Pierce had had enough of the “costly and unnatural sacrifice” of her talents and intellect to “the dusty drudgery of house ordering,” which meant ceaseless rounds of scrubbing, cooking, and entertaining. That a woman should spend life on such a treadmill of toil seemed to Pierce a complete waste, not to mention dangerous. Housekeeping demands carried off her mother prematurely, she believed. And she herself was beginning to feel the strain of many hours stooped over steaming pots of beef broth and calf’s foot jelly.

Pierce was determined to throw off the shackles of housewifely bondage. A descendant of the outspoken colonial settler Anne Hutchinson, rebellion ran in her blood.

Pierce also advocated for the founding of Radcliffe College.

Educated at Professor Louis Agassiz’s Young Ladies’ School nearby, she often joined her husband, a lecturer on the philosophy of science at Harvard, in his investigations.

“The labor of women in the house, certainly enables men to produce more wealth than they otherwise could; and in this way women are economic factors in society. But so are horses.” —Charlotte Perkins Gilman

The solution Pierce hit upon she regarded as a matter of common sense. Women were once the economic equals of men, she knew. They needed simply to learn this historical truth, and it would set them free. And so she set about informing the educated women of Cambridge that their colonial forebears made important economic contributions to the household, and that, in fact, these contributions were just as profitable as those of their husbands. They assisted with crops and animal husbandry. They wove cloth and sewed garments from it. They made soap, candles, and sundry other household items. In these ways and others they kept their homes flush.

"The present unsatisfactory condition of domestic labor in private houses is not confined to any special city or country; it is universal. Each year the difficulty of obtaining women to do housework seems to increase and the demand is so much greater than the supply, that ignorant and inefficient employees are retained simply because it is impossible to find others more competent to replace them." --From Clara Hélène Barker's Wanted, a Young Woman to Do Housework: Business Principles Applied to Housework (1915)

"A 'gainful occupation' in census usage is an occupation by which the person who pursues it earns money or a money equivalent, or in which he assists in the production of marketable goods. The term 'gainful workers,' as interpreted for census purposes, does not include women doing housework in their own homes, without wages, and having no other employment ... nor children working at home, merely on general household work, on chores, or at odd times on other work." --From the Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930

Industrialization ruined this arrangement. With the rise of factory work the erstwhile plucky housewife found herself subordinated to her wage-laborer husband. She remained in the home, left with just as many chores as before. Yet in performing them she no longer received the financial recognition enjoyed by her pre-industrial predecessors. Her condition Pierce deemed “the most fruitful source of disorder, suffering, and demoralization.” It moved her to pen her 1880 book,

Cooperative Housekeeping: How Not To Do It, A Study in Sociology. "Surely it is not to be denied that we are all on a dead level of mental achievement and social consideration,” she notes in it, “and that we are growing less valuable and less valued, because less helpful, all the time.”

“The Family is a petty despotism … A school in which men learn to despise women and women to mistrust men (much more than is necessary); a slaughterhouse for children (the firstborn succumbing to unskilled treatment, the last born to neglect) … Unfortunately, we cannot as yet do without it; and therefore we put a good face on the matter by conferring upon it the conventional attribute of sacredness, and impudently proclaiming it the source of all the virtues it has well-nigh killed in us.” --George Bernard Shaw, “Socialism and the Family” (1886)

Restoring this value would come through cooperation -- economic cooperation, to be precise. And cooperation began, naturally enough, at home. Pierce sketched out how this would happen. Cooperative associations of twelve to 50 women would perform important domestic work together, and each member would charge her husband accordingly. This scheme would lighten a woman’s workload while enabling her to amass resources of her own. Each woman who joined would pay a membership fee. The money paid would go toward furnishing the cooperative’s headquarters with necessary equipment for cooking, baking, laundry, sewing, and toward purchasing food.

Pierce envisioned her cooperative’s headquarters as a marvel of efficiency, her goal that of securing members’ comfort. The ground floor would hold rooms for accounting, sales, consulting, and clothes-fitting. The second floor would hold rooms for sewing, cooking, and other typical household work. The third floor would feature a dining room, gymnasium, and library. The design of this floor would be such that, on the occasion of some social event, doors could be opened to create a single large space.

"In many respects the cooking area is the most important part of the house, yet it is often the poorest. How many houses in your area have a nice looking and comfortable living room in which company is invited, but a dark, poorly equipped, and unsanitary kitchen where the housewife has to prepare meals for the family? Home improvement often begins with kitchen improvement." --The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Extension Service's Program Aid, Issue 953 (1971)

Pierce’s concern for the comfort of her cooperative's members is understandable, if unusual, for a time during which the things of their lives -- shoes, corsets, childbirth -- conspired to hurt them. Indeed, Pierce wanted her workers to enjoy themselves as much as their work would permit, urging them to wear trousers and short skirts. Easy chairs situated throughout the cooperative’s headquarters encouraged lounging. And she decorated the place, believing its appointments would refresh members in body and soul. She imagined also that the beauty within the cooperative headquarters would promote beauty beyond its doors, as women, having centralized their domestic duties, would opt for simpler housing. From this would come something of an urban renewal. “Houses without any kitchens and ‘back-yards’ in them! How fascinating!,” Pierce writes. “Think how much more beautiful city architecture will be now!”

Fascinating is how many American women found Pierce’s cooperative housekeeping. In large towns and small, women sought ways of sharing the burden of their chores. In an address to women's group in Carthage, Missouri, a former senator of that state complained that his wife “is always cooking, or has just cooked, or is just going to cook, or is too tired from cooking.” He followed his maundering with a plea: “If there is a way out of this, with something to eat still in sight, for Heaven’s sake, tell us!”

“I … understand why the saints were rarely married women. I am convinced it had nothing inherently to do, as I once supposed, with chastity or children. It has to do primarily with distractions …Women’s normal occupations in general run counter to creative life, or contemplative life or saintly life.” --Anne Morrow Lindbergh

The women of Carthage did better than tell the exasperated senator how to relieve his wife. Perhaps inspired by Pierce, who had managed to establish the Cambridge Cooperative Housekeeping Association some 20 years before in 1869, together they rented a large, white clapboard house conveniently located near the business district and a streetcar stop. They filled it with dining tables and chairs, tablecloths, napkins, and silverware -- all brought from home. From the windows they hung muslin curtains. They transformed one of the rooms on the first floor into a music room, another into a library. The largest room they made into a dining room that could accommodate 60 people.

“It is the terrible waste of force that modern housekeeping represents -- waste not only in expenditure, but in results. Each kitchen has its Moloch in the cook-stove, the shrine before which ‘a passing train of hired girls’ incessantly does homage … ‘We have no time for anything,’ is the cry of all women, yet not one of you is willing to submit to the personal trouble that might be involved in a new experiment, or to work out for the world, as it must be worked out, all that belongs to this business of cooperation. Every sign of the times shows that it must come.” —“Is Woman Embodied Obstruction?,” The Arena, Vol. 15 (1896)

Thus was born the Carthage Cooperative Kitchen. Seating was determined by lot, and enough space was left between tables to ensure privacy. In the Kitchen’s early days, each family brought their own table, adding to those that were already there, and each also supplied their table with linen, cutlery, and condiments. To help with meal service, the cooperative hired a dishwasher -- who was reportedly "most difficult to keep" until a "substantial increase" in wages was made -- two waitresses, two cooks, and a few servants. All were given extra time off to make up for long days spent cooking. As the organizers noted, "it is much pleasanter to work in the Kitchen than in a kitchen."

Prices were reasonable. Adults were charged $3.50 per week, or about $88 in today's money. Children under seven and over two years of age were half price. Servants paid a two-third rate, if they elected to forego a waited table, and guests for single meals paid 25 cents, which would be about $6.26 today.

The food to be had for these prices was impressive in terms of variety and portioning. Here’s a sample menu:

Breakfast: Cereals, Tea, Cocoa, Coffee, Hot Cakes, Delicious Broiled Ham, Lyonnaise Potatoes. (Children may have eggs, milk, or cereals at any meal. Eggs and bacon are frequently served for breakfast.)

Luncheon: Chicken Salad, Macaroni and Cheese, Hot Biscuits, Apple Sauce and Gingerbread, Tea, Chocolate, Coffee.

Dinner: Broiled Porterhouse Steak, Stuffed Baked Potatoes, Home-made Boston Baked Beans, Home-made Boston Brown Bread, Lettuce, French Dressing, Blanc-mange, Orange Sauce, Coffee.

Bread was served three times a day. Diners could choose light bread, raisin bread, nut bread, or rolls. And twice a week, salt-rising bread made it to table.

The Carthage Kitchen proved a smash. “I’m down as a life-member, let me tell you right now!,” enthused the husband of one member. “The meals may be plain but they are balanced. The quality makes up for any amount of frills and trimming.” More festive food was served on birthdays, holidays, and other occasions, during which members were treated to special feasts and even presents.

Few tasks are more like the torture of Sisyphus than housework, with its endless repetition: the clean becomes soiled, the soiled is made clean, over and over, day after day. —Simone de Beauvoir

For all its success, the Carthage Kitchen did face certain difficulties. Families with a greater sense of entitlement than others presented a challenge. The manager had to ensure they received the “service” they expected, all while ensuring that everyone else was served to satisfaction, too. And then there was the subtle but persistent influence of the kitchen utensil manufacturers, who, through advertising, tried to convince American housewives that liberation lay not in cooperative kitchens but in buying electric appliances that would make cooking a woman’s “pleasure to attend to” and ensure she “shall be vexed no longer with proffered solutions of the domestic problem, for there will be no domestic problem to solve,” as an 1896 issue of

The American Kitchen Magazine put it.

When asked what he thought of a club in Utica, New York, which ran from 1890 to 1893, one dour man said that had the club survived "his wife would probably be alive now."

The come-ons of salesmen and admen managed to do little. The Carthage Kitchen flourished for four years, until catastrophe finally shuttered it. A long drought drove up food prices, which in turn drove up the price of membership. Families dropped from the rolls, electing to eat at home again, and the cooperative folded.

No member of a crew is praised for the rugged individuality of his rowing. --Ralph Waldo Emerson

The idea that cooperation could make life easier took hold of the American imagination. In Warren, Ohio the Mahoning Club appeared. Slightly smaller than the Carthage Kitchen, it served 22 members. Many of those members were professional women who had no time to cook at home but yearned for home-cooked food. Indeed, professionals of both sexes frequented the Mahoning Club, and they could be found doing their share in the kitchen. Together the members of the Mahoning Club created a place that became famous for its “common sense, good management, and friendliness.”

“True, O Hestia! goddess of household virtues, it is yet in the days of its youth; but it bears not the marks of a weakling; it is sturdy and growing and is fast leaving immaturity behind. The cooperative kitchen is a possibility. Properly managed, it is a success.” --“The Longwood Co-operative Kitchen,” Good Housekeeping, Vol. 32 (1901)

In Jacksonville, Illinois, Sioux City, Iowa, Junction City, Kansas, Decatur, Illinois and dozens of other towns throughout the Midwest, these cooperative kitchens thrived. They did so in part because, as Pierce herself predicted, fewer class distinctions obtained in Midwestern towns, and Midwestern townswomen weren't afraid to get their hands dirty, no matter the class they belonged to.

Recipe for Luncheon Beef and Macaroni in Tomato Sauce from The Business of Being a Housewife: A Manual to Promote Household Efficiency and Economy (1917): "1 can Veribest Luncheon Beef, cut in cubes; 1 cupful macaroni, cooked tender; 4 cupfuls canned tomato puree; 1/2 cupful Armour's Oleomargarine; 1/2 cupful four; 1 teaspoonful salt; 1/2 teaspoonful pepper. METHOD: Cook the macaroni in rapidly-boiling salted water until tender. Press enough canned tomato through a sieve to make four cupfuls of thickish liquid (purée) (Veribest Tomato Soup may be used). Melt the Oleomargarine, in it cook the flour and seasoning, add the tomato and stir until boiling; add the macaroni and meat and let stand undisturbed over boiling water until very hot."

“Wealthy families will always be able to secure a satisfactory resident cook who has been trained in the best European or American schools, but for families of modest means it looks as if the cooperative kitchen would be the ultimate way out of the difficulty.” —“The Cooperative Kitchen,” The Public: A Journal of Democracy (1898)

And perhaps they thrived because in small Midwestern towns communal ties remained strong. For the cooperative kitchen was, in essence, a neighborly endeavor. Members of Junction City’s Bellamy Club, for example, were enjoined always to remember “that they are not in a boarding house carried on for the purpose of gain, but are members of a mutual cooperative society, whose members give their time and energy to the work without any recompense except that shared by all, viz., the successful working of the club.” Though ultimately the clubs didn't succeed, they showed that there's an alternative way to the for-profit, outsourced "solutions" so prevalent today. Perhaps that way will open once again.