By Robert Davis

In 1876, the Centennial Exhibition, the first United States world’s fair, opened in Philadelphia to celebrate the nation’s 100 year anniversary. With its mission mandated by Congress to showcase “the nation’s progress in arts which benefit mankind,” the exhibition, which spread across 285 acres, included displays of natural resources, art, wildlife, horticulture, and historical artifacts, among others. As a self-consciously epoch-making event, countries, states, and corporations were eager to present their accomplishments. To be included in the exposition was to claim a share of American progress, something that a group of women hoped to do by erecting their own Women’s Pavilion at the Centennial. The representation of women at the exhibition, especially as inventors and technologists, created a controversy about the role of women in public life in 19th-century America.

Women were involved with the exposition from the planning stage. The Board of Finance created a Women's Centennial Executive Committee to help with fundraising, and when the Committee raised more than $2,000,000, they were granted exhibition space in the exposition’s flagship 20-acre Main Building. Although the Women’s Committee members were hopeful that this signalled a shift in the representation of women in public spaces, they were soon disappointed by the all-male Centennial Board, which sold the space to outside exhibitors and informed the Women’s Committee that it would have to finance and construct its own building. The Women’s Committee quickly rallied to plan, fund, and build a freestanding 30,000 square foot Women's Pavilion. Although it was designed by a man, all of the exhibits inside, ranging from art to needlework to new farming equipment, were created by women. It was the first international exhibition of American “women’s work.”

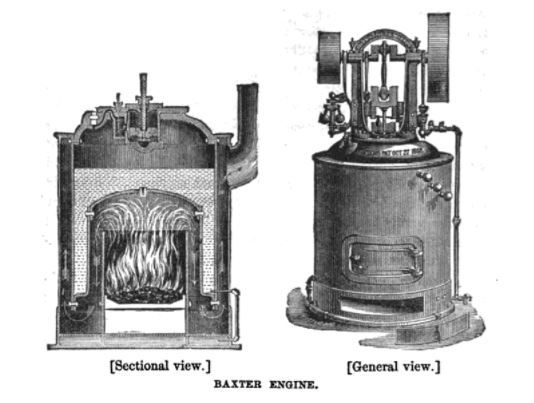

A brick addition to the Women’s Pavilion housed the Baxter Portable Engine, a six-horsepower steam engine that powered the building’s machines, including a printing press that published pamphlets and a weekly newspaper, The New Century For Woman. The Women’s Committee wanted to show that women could design and operate industrial technology and, thus, contribute to industrial progress. The Baxter Engine, and its engineer Emma Allison, became a focal point of the ensuing debate about a woman’s right to enter technological fields.

Baxter Engine, Souvenir of the Centennial Exhibition (1877), by George D. Curtis. (Google Books | Public Domain)

All exhibits in the Pavilion were staffed by women, including the Baxter Engine. During open hours, Allison operated all aspects of her “iron pet.” She started the fire in morning and stoked it throughout the day, maintained the correct pressure, and shut it down at night. She also played the role of public ambassador, presenting the machine to fair visitors, all while dressed in her Sunday clothes to show how easily she could perform the labor.

Almost immediately, Allison’s role operating the Baxter Engine became a subject of curiosity and speculation. At a time when many feared that increased social responsibilities would cause women to abandon their “proper” duties as wives and daughters, the Women’s Pavilion experienced pushback from the beginning. The New Century reported that “there was, of course, much opposition to the project, one of the arguments used, not in the committee but by outsiders, being that the committee would some day find the Pavilion blown to atoms and it would be discovered that the female engineer had lost herself in some interesting novel when she ought to have been watching the steam-gauge.” The increase of both women entering the workforce and partaking in new entertainment crazes, like reading novels, caused tremendous anxiety among advocates for traditional gender norms. Women's enthusiasm for reading novels, which were depicted as a “moral poison,” was a documented social "problem" in this period, causing many doubt that women were capable of taking an equal role in society.

The New Century presented Allison as a natural feature of modernity, noting that Allison was “overrun with visitors, who gazed upon the strange, yet, in this age of progress, not unexpected spectacle.” An article in the July 8, 1876 Saturday Evening Post saw Allison’s demonstration, in which “she gave a deeply interesting account of the different parts of the engine and the manner of running it, etc.,” as a sign of social change. The Post wrote that “the ease with which she accomplishes the management of her busy machine, the care of which has hitherto been deemed to lie essentially within man's province, marks a decided epoch in female labor.”

Scientific American treated her as a one of the many things on display, noting that “[p]erhaps the most interesting object … in the woman's edifice is the lady engineer.” A Philadelphia Times article that was reprinted widely focused on her appearance, pointing out that she was “by no means a soot-begrimed and oil-covered Amazon,” perhaps to remind the reader that running a machine did not compromise Allison’s performance of proper gender norms. According to The New York Times, the displays in the Women’s Pavilion were unfeminine because the women who talked to the public were driving “visitors away by black looks or surly answers” and were “exceedingly disagreeable and disobliging.”

Perhaps to counter these criticisms, Allison regularly held court on her upbringing and vision for the future. She told visitors that she first became interested in machines as a child, and chose to spend her time in the mills that her father owned in Ontario. When asked about the future, she observed that there were thousands of machines in operation in the U.S. the size of the Baxter engine and saw no reason why women couldn’t run them. While some questioners expressed dismay that a woman could do such work, Allison replied that it was easier than being a nursemaid and less tiring than bending over a stove. She took the point further and criticized how male engineers kept slovenly machine rooms, something that women engineers would presumably not tolerate.

While the Women’s Committee could present women as productive members of society, it had to avoid radical political positions like suffrage. Neither The New Century or the pamphlets advocated for suffrage, nor did the Women’s Committee welcome suffragist organizations, which had to open parlors in private Philadelphia homes to discuss radical platforms. The Women’s Committee did not grant black women exhibition space despite their having worked to raise money for the building’s construction. The Women’s Committee denied Susan B. Anthony and her cohort inclusion in the exhibition’s official centennial celebrations on July 4, 1876. However, radical women refused to stand at the margins of the fair. While several male dignitaries gave speeches about American liberty during a large parade and ceremony at Independence Hall, Anthony occupied the stage and read the “Declaration of Rights for Women” as activists handed out copies of the document.

It is tempting to read the 1867 World’s Fair as groundbreaking moment for women in public life, but the criticism leveled at the Women’s Pavilion and Allison’s experience highlight the broad limits placed on women claiming public space. Keeping women out of political and labor spheres was an important tactic in political control in the 19th century. The next U.S. World’s Fair, in New Orleans in 1884-1885, denied its Women’s Committee a separate structure and gave them less exhibit space than in Philadelphia by placing the displays in a wing of the U.S. Government Building. According to one reviewer, the Women’s Department was “wholly and of necessity inadequate to present a view of the attainments of women in the industries and arts, and their share in carrying forward the world’s civilization.” It was not until the 1893 Columbian Exposition that American women would earn another space of their own in a world’s fair.

The 1876 Centennial was a key debut for women inventors, engineers, and artists that highlighted both the successes and struggles that women faced as they organized to claim public space in science and society, but it was not an unqualified victory. Much of the documentation of the Women’s Committee remains unpublished in archives. If brought to light, it could reconstruct a vital moment in history when women were breaking into new fields of labor and representation.

Further Reading

T. J. Boisseau and Abigail M. Markwyn, eds., Gendering the Fair: Histories of Women and Gender at World’s Fairs (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010).

Bruno Giberti, Designing the Centennial: A History of the 1876 International Exhibition in Philadelphia (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2002).

Mary Francis Cordato, “Towards a New Century Women and the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, 1876,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 107, no. 1 (1983): 113-36.

Louise Krasniewicz, “The Life and Adventures of Emma Allison.” https://emmaallison.me/