In Our Aesthetic Categories, Sianne Ngai argues that cuteness, interestingness, and zaniness are the characteristic aesthetics of our "late capitalist" age. While it seems somewhat arbitrary to limit the possibilites to three, I can easily see how these can be used to taxonomize most people's online presence: There aren't many that can't ultimately be reduced to attempts to be cute, interesting, or zany.

Ngai links the promience of these categories to neoliberalism and our ambivalent response to its demands for flexible subjects, immaterial labor, real subsumption, and progressive commodification of experience. They might also be regarded as a consequence of "networked subjectivity" and the idea that we must circulate signifiers of the self to give that self concrete reality. Once, we could convince ourselves we have a self by paying attention to our own interiority — by listening to the voice(s) in our head. Social media, and the direct social proof it can offer, render interiority insufficient. So we must marshal an audience with a style of self-performance that is appropriately scaled to the attention we can reasonably expect for it ("cute") or is explicitly concerned with virality, with being compulsively "interesting" — an identity worthy of a reblog. The value of any given signifier as a marker of the self depends not on its content but on its circulation. The "truth" about the self stems from how it gets retransmitted, not what it originally or uniquely contains.

In this sense, social-media users today are where the pioneering video-artists of the 1970s once were. Rosalind Krauss, in a 1976 essay called "Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism," condemned the effects of self-documenting art on the art world in general, pointing to the way it shifted emphasis to circulation and feeback:

In the last fifteen years that world has been deeply and disasterously affected by its relation to mass-media. That an artist's work be published, reproduced and disseminated through the media has become, for the generation that has matured in the course of the last decade, virtually the only means of verifying its existence as art. The demand for instant replay in the media-in fact the creation of work that literally does not exist outside of that replay, as is true of conceptual art and its nether side, body art-finds its obvious correlative in an aesthetic mode by which the self is created through the electronic device of feedback.

It's not hard to link the "self created through the electronic device of feedback" — for Krauss, the quintessential "mode" of all video art — as a description of social-media use, much of which can be regarded as a kind of phatic mic check: "Is this thing on? Can you hear me? I am here!" Just as artists needed to verify their status through circulation in media, we need to verify our social selves through circulation of artifacts in social media. So like video artists, we are conscious of reframing our life activity as shared performance. The depth or complexity of one’s subjectivity can no longer be used to measure how authentic one’s art is, or how authentic one's self is. Authenticity (which is almost always a code word for validation or recognition) is a distributed phenomenon.

But the search for validation on social-media is complicated by the fact that our audiences are always also performing — are artists in their own right. In Ngai's analysis of the "interesting," she quotes a passage from 1970 by Joseph Kosuth, American editor of Art-Language, a conceptual-art journal: "The audience of conceptual art is composed primarily of artists—which is to say that an audience separate from the participants doesn't exist. In a sense, then, art becomes as 'serious' as science or philosophy, which doesn't have 'audiences' either. It is just interesting or it isn't."

Kosuth seems to be talking about how sheer facticity can protect artists from the shame of pandering to audiences. But it may be, as Krauss's claims about video narcissists suggest, that one can also circumvent pandering through solipsism. Social media use, too, is beset by the problem of pandering, and many users adopt aggressive self-promotion as a guaranteed way of seeming sincere: "You know I am not lying about wanting your attention and approval." Shameless pandering seems without guile, which then makes it seem like the opposite of pandering, like some kind of daring devotion to honesty.

But what really forestalls accusations of pandering is that all social-media consumers are also users who are vulnerable to the accusation themselves. We can't pander to one another because we are all insiders, technicians of the medium. With both conceptual art and social media, the audiences are also performers and are "serious" about the medium and concerned about strategies for using it. Social-media consumption thus has a meta component built in to it that nonsocial media don't — most people don't watch TV shows with the intent of making their own (though arguably, I suppose, some of the same techniques could be appropriated for self-presentation in Facebook, etc.). But consuming social media is often about absorbing how to create social media better — that, and not the specific things mentioned, can be the primary content for consumers.

Our consumption of social media, then, is always inflected by potential jealousy for rivals in the medium or by the alertness for techniques or ideas to borrow. This can complicate the hope we have in using social media for creating an appreciated self, an archived identity that has followers who validate it for its particular content. It tends to makes the self merely a set of techniques for self-documentation rather than a matter of what it is documented. (I am real because my social media presence is active, not because of anything I say on social media.)

The tension between personal experience (the thing itself) and the need to share it to make it mean something has always existed, but social media certainly intensifies it. It leaves social-media users with no excuse for not immediately seeking social confirmation for the awesomeness of whatever experience they have just undergone. The need to share seems to overlap experience, so that all experience is sharing: We are the video artist pointing the camera at ourselves always to make what we are doing into a "life." Into life as art, as truth — there is documentary proof that things happened. Ngai notes how "the photographic series" was the main mode of conceptual art in its heyday; it is also a chief mode of casual social media use — sharing a stream of photos whose content can be of minimal interest as long as it is part of an ongoing project of sharing and documenting the self.

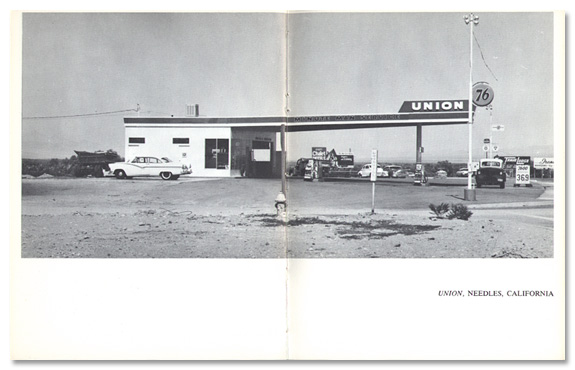

The reciprocity of our being audience for one another has the effect not of emphasizing the "interestingness" of the content but of making the content more like an indifferent placeholder in the game of exchanging gestures of attention and recognition within the network. Circulation of ideas becomes the idea, the content of the ideas being circulated a matter of happenstance. This was why conceptual art could be Ed Ruscha compiling a book of images of gas stations, and why Instagram feeds can be a bunch of pictures of breakfast. What is "interesting" with respect to such media unfolds over time and is not revealed as a flash of captivation, as we are sometimes prone to think of it.

Taken to one logical extreme, social media as self-documentation becomes self-quantification as democratized conceptual art. The quantitative self is a conceptual artwork driven by quantitative logic, just like Ruscha's. It's intentionally boring and inane in any isolated moment, since its purpose is to nullify the moment of interest and stretch the self's potential interestingness to infinity as the data compiles to make up charts and graphs and so on. Like minimalist art, it eliminates subjectivity and creativity and, to some degree, intentionality from the documentation of the self. It becomes "pure."

Ngai quotes literary historian Franco Moretti on detective fiction to describe Ruscha's mode of linking "continuous novelty of content to a perennial fixity of the syntax." I think that's a good description of social-media platforms. Social media invite "experiments in inertia" (to borrow a phrase from Roger Shattuck's description of Satie): continual additions and variations on themes hard-coded into the platforms.

Moretti's phrase also captures the epistemological approach of self-quantifiers, who are thrilled to derive aesthetic pleasure in themselves by using a systematic approach to render their life experience "interesting." Objectively interesting, too — remaking life as data makes it seem universally significant ("quantities are always informative," Ruscha claims), not a contingent form of purely personal nostalgia. Self-quantification, then, may be an attempt to make personal nostalgia somehow more "legitimate" and less a vertiginous private hole one's mind can fall into.

In Ngai's scheme, conceptual art played a part in establishing the definition of the "interesting," helping establish it as an aesthetic category in its own right rather than the purported opposite of an aesthetic (i.e. "it's not good, but it's interesting"). The "interesting," she suggests, is a response to consumer capitalism's overwhelming us with novelty; it describes and valorizes the sort of pattern recognition that is never complete, and it is always in danger of collapsing into boredom, of seeing insignificant variations in commodities, say, not as novelty but as more of the same. Something is interesting when we can't immediately resolve why it has piqued our curiosity or held our attention. It calls attention to the process of being attentive, frames "paying attention" as a kind of important work in and of itself, regardless of what is attended to. Hence "interesting" is the aesthetic category Ngai associates with circulation, with the affective force that yearns for seriality and keeps information moving.

This seems relevant to the frequent complaint that the stuff many people share on social media is "boring" — as though the specific, discrete updates or images are even the point. Each isolated update is almost structurally doomed to being boring because its chief function is to gratify our wish to long for the next one, to provoke our curiosity for what's coming — to make our "interest" palpable in the trace of its evaporation, as we consume any given image and yawn.

If any given update or image is too fascinating, it upstages the accumulating archive of self as the center of interest — it halts it. For instance, if any one of Ruscha's gas-station images is too interesting, it voids the integrity of the project as a whole. The book would become subordinate to the outstanding image it contains. You wouldn't need to take on the book as a whole any longer to appreciate its genius.

Likewise for social media use. The user's self in social media is akin to those conceptual artworks (or novels — I'm thinking of Richardson's Clarissa) that work chiefly in time rather than space. The sum of things shared are more compelling in their flow, in the way they tame diverse experience into an underlying homogeneity required by the social-media platforms. The point of this is to secure social recognition and validation of the self, as a dynamic but socially real thing, a coherent concept that takes its stable form as an open-ended progression over time. The self is legitimate as a format.

But an overly interesting image diverts the audience's attention from the flow, reorients their attention to the singular update. This means that the force of the social recognition audiences supply is diverted away from appreciating the ongoing life one chronicles through social media use; instead recognition suddenly becomes contingent on whether a user can deliver spontaneous moments of true fascination. You get upstaged by the brilliance of what you've shared.