In his essay for the Baffler about the disappointed expectations about flying cars and whatnot, David Graeber makes the often overlooked point that capitalism circumscribes technological development as much as it instigates it. In other words, technology can be developed to protect the status quo, not trasform it. When corporations and the governments that serve corporate interests look to fund technology, the criteria relate to whether the expected fruits will serve to reproduce the existing order of things — that is, whether the technology will strengthen capitalism. The criteria is not necessarily whether overall human life will be improved, obviously. (For example, Klout exists.)

Apologists for the market frequently claim that it processes information to allocate resources and adjudicate the distribution of goods in the ways most conducive to human flourishing. Technology is thus best oriented toward making markets "more efficient" and more comprehensive. If we let the markets rule more of life, more of life will be subject to its benign evaluation for the good of everyone. The market, that is, allegedly overcomes parochial interests. Hence we increasingly use technology to perform real-time price discrimination and to make heretofore unmarketable aspects of social life into exchangeable commodities or experiential goods — on the basis that this is for our own good, as it allows us to use market outcomes to see the true value of our choices and our efforts.

Michael Sandel is justly worked up about how "markets crowd out morals" and undermine social norms, but that's because the view that markets are wise and fair collective-action problem-solvers has come to seem like common sense. But markets don't solve for human flourishing necessarily; they solve for capitalist control. They process power differentials neutrally, with no mechanism for diminishing them, and ignore all human desires that have no money backing up their urgency or sincerity. Also, market propaganda shouldn't blind anyone to the fact that markets are designed and shaped through laws (so called good governance) meant to protect the interests of the already powerful; markets aren't manifesting some transcendent law unto themselves.

Closer to the truth about markets and technology are the warnings of conservative "futurists" like George Gilder and Alvin Toffler, who as Graeber points out, helped convince politicians that in the second half of the 20th century that "existing patterns of technological development would lead to social upheaval, and that we needed to guide technological development in directions that did not challenge existing structures of authority." Technology needed to yield consumer goods that could placate the otherwise disenfranchised; it shouldn't empower such people to be able to have more of a say about the shape of the society in which they are embedded.

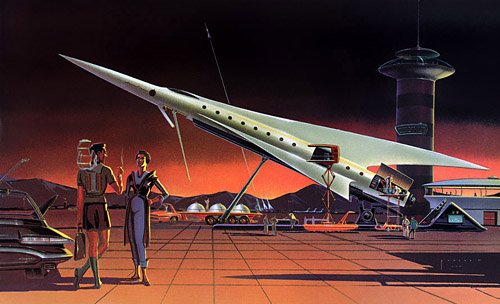

With that in mind, Graeber makes some suggestive claims about neoliberalism's rise in the wake of the Soviet Union's decline. After noting that technology under the guidance of neoliberalism has not yielded moon bases and jet packs but instead mood-stabilizing medications and rentier-serving debt instruments, Graeber writes:

With results like these, what will the epitaph for neoliberalism look like? I think historians will conclude it was a form of capitalism that systematically prioritized political imperatives over economic ones. Given a choice between a course of action that would make capitalism seem the only possible economic system, and one that would transform capitalism into a viable, long-term economic system, neoliberalism chooses the former every time. There is every reason to believe that destroying job security while increasing working hours does not create a more productive (let alone more innovative or loyal) workforce. Probably, in economic terms, the result is negative — an impression confirmed by lower growth rates in just about all parts of the world in the eighties and nineties.

In other words, technology has not been directed entirely toward improving productivity, as is often assumed under the logic the capitalists are solely looking for an edge to reduce production costs. Rather, technology also serves the purpose of intensifying ideology, which is why so many technological developments recently have been in the field of communications. Technology is being used to foreclose on alternatives, Graeber suggests, not open them up. Technology has evolved to posit path dependency rather than expand the possibilities for social change and permit groups the opportunity to try different ways of life. Capitalism's prerogatives make us assume that path dependency is the natural outcome of technology rather than a product of vested interests protecting their future. As Graeber notes, "There are many forms of privatization, up to and including the simple buying up and suppression of inconvenient discoveries by large corporations fearful of their economic effects."

Instead of pursuing the inconvenient discoveries that might make everyone's lives better, corporations have chosen to prefer technologies that enhance social control — surveillance, drones, social media, etc. — the developmental equivalent of prioritizing guard labor over productive labor. "Basic research now seems to be driven by political, administrative, and marketing imperatives that make it unlikely anything revolutionary will happen," Graeber claims, arguing that research conclusions are more or less preformatted by the expectations of funders.

Shoshana Zuboff wrestles with this same problem at the end of her 1988 book In the Age of the Smart Machine. She wants to paint an optimistic view of how technology will liberalize "posthierarchical" workplaces and do away with reified class distinctions between managers and the managed and enable capitalism to fulfill its mission of getting the most out of all its workers and leaving them gratefully fulfilled with "meaning" by the process, but her own ethnographic work in the book makes it extremely difficult to make the case. And neoliberal workplaces aren't posthierarchical; they are destructured, with increasing numbers of people doing contract work but with no leverage over their employers. Levels of the hierarchy have been wiped out through attrition and layoffs, not through a harmonization of various workers' job function and their sphere of authority. Technology has allowed employers to find more and more free labor and put more and more downward pressure on wages. Workers have to work harder and longer to justify their necessity; that's the form that the once-promised autonomy has taken under neoliberalism.

Graeber suggests that neoliberalism endangers itself with this program of immiseration, producing a restless "precariat" and engendering a basis for more trenchant critique of capitalism. But technology won't automatically yield growth in a critical or progressive consciousness:

But the neoliberal choice has been effective in depoliticizing labor and overdetermining the future. Economically, the growth of armies, police, and private security services amounts to dead weight. It’s possible, in fact, that the very dead weight of the apparatus created to ensure the ideological victory of capitalism will sink it. But it’s also easy to see how choking off any sense of an inevitable, redemptive future that could be different from our world is a crucial part of the neoliberal project.

This is very reminiscent of Peter Frase's essay about how capitalism may evolve to accommodate labor-saving technology and produce artificial scarcity. The point is that technology doesn't necessarily guarantee abundance — it doesn't "want" human freedom — but can be directed instead toward exacerbating want and intensifying desire or feelings of exclusion. It requires concerted political effort to point technology at other aims, particularly when capitalism is well served by making people feel hungry and discontented.

As another futurologist once put it, "This ain't rock and roll; this is genocide."