[Part 1 of a two-part]

Then we should have a paradise on Earth and would not need to gaze longingly at the paradise in the sky.

(Paul Scheerbart, on what would happen if glass architecture was everywhere)

---

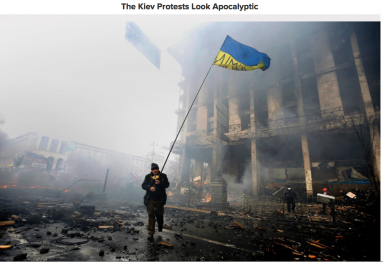

Before the accusations of exactly who was trying to start World War III, before takeovers of police stations and uniforms of unmarked but totally obvious origin, before the peacocks and the tall ships and koi and garage full of Rolls and the Crimean back and forth, before all that, in Kiev, in Maidan before March, there were scenes that news outlets clickbaitishly couldn’t help themselves from calling “apocalyptic.”

Why that particular designation, though? Why do they or we name something that happens now as apocalyptic, especially when it isn’t intended to mean the event in question will be the creeping start of The End?

The appropriately flat NBC News title – "The Kiev Protests Look Apocalyptic" – makes it plain. It has almost nothing to do with what is happening, or indeed, with what that could mean for an "apocalypse" of geopolitics, as configurations and allegiances tactictly in place get brought into relief through turbulence. Instead, the designation gets made because of distinct content and texture in the images: not just the riot, or the riot plus toppled statues flanked by fire, or even the riot + statues + fire + ice + DIY armor + an old man carrying a scrawled-on flag through the shell of a city. Rather, it's all of it, all amidst and below an off-setting haze of grey and particle effects caused in part by this very content, as smoke, ash, slush, trash, and tear gas is suffused with winter light and backed by a week-old skim milk sky. And in front of this, cops gather for a Little League team portrait. They put riot shields over their heads, Roman centurion tetsudo formation.

Two specific visual properties result from this and perhaps impel the description from the start.

First, there's that flat light, one in which shadows are not cast, even if much of the visual field is taken up with shades of grey and black and dusky brown. A pallor or shade cast over everything, yes, but coming from nowhere in particular, not falling from a body, a burnt bus. And so too the light. Not a sun to be seen, yet things are bright amongst the grey while the sky itself just sort of is light, a tablet of light, a light box, light tent without distance or scale, near and far at once. (It's the sky and air of Saramago's Blindness but as a condition in the world, not in the eye itself.)

Second, though, this null clarity and consequent flatness get counterposed by minute details that demand attention all the way through the volume of the photographed scene. There's snow in the extreme foreground that cannot be held in focus if we are to see the riot in the back, and iced branches at imagined arm's length too pretty to not dwell on. Figures throw objects from one plane to the next, near to far, in shot to out, as mid-ground smoke blocks what stands behind and signs and wires pop through that. Further back, ghosted buildings recede into the milk-light. And through all of it, pavement and air alike are cluttered with assorted bits of city, small collections of rubble and flakes and puddles that reflect it all.

What got labelled apocalyptic, then, is not just a color palette joined to a checklist of adequately busted, tossed, flipped over, and scorched things. It's also a distinct way of constructing images of space, particularly of a built world on uncertain ground. It combines a sheer buzz of detail and dense patterning with a flattened light (and slightly downward angled lens) to produce images where recognizable forms that can be precisely located and historically specified (this riot, that city) threaten to tip into a depthless surface of effects – of particles, motes, chaff, splinter, cloud. (In short, into shards.) Probable cause vanishes into an undecided either/or: things loll in the air or are thrown, billow up or simply hang , are fired or happened to fall, are themselves on fire or just hotboxed with tear gas and soot. A highly territorial situation, one where control of space and its social parameters are fought over bitterly, comes to generate the conditions for an image of what could just as well be digital after-effects laid over the composited frame of a city. Properties or ornament. Ash or snow. Available Instagram filters: Hot Winter or Burning Square.

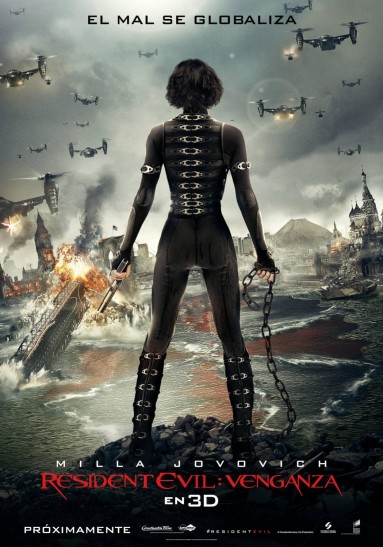

This quality of light, drifting material, disarray, and spatial consequence "happens" to align with what has become doomsday de rigeur, dominating the last decade and a half of apocalypse-minded visual culture.

Below and in front...

above and from behind... ("Evil goes global")

In a more fitting confirmation of this pattern, consider this image of apocalyptic Maidan, made by Ivan Khivrenko, a video game artist and illustrator, well before the riots there:

Fallen angel statue, tattered flags, and, of course, a thickly grimed/frosted ground on which water sits - all the better to reflect the wrath of heaven/sky by Thomas Kinkade - and over which smoke thickens all illumination into beams and stains.

If "apocalyptic" has hence come to indicate a certain way of constructing spaces of disarray as both historically and visually flat images, it also serves a secondary spatial function, an ultimately territorial one that polices the entirely blurry edges of division between Global North and South. It works to decide just where that mess belongs.

In one way, apocalyptic designates what no longer fits within a – the, it wants to insist, the – history of allegedly progressive and coherent capitalist order. Apocalypse becomes the plain name for a situation that finally stretched that order too thin, causing a break not just among its zones, territories, and regimes but with its history in full. Calling the scenes in Kiev “apocalyptic” means: not the North anymore, not the West we once knew.

However, through this very process, apocalyptic serves to all the more distinguish its named terrain as presently West and North, because it claims the eruption or damage as exceptional. So exceptional, in fact, that it can only be grasped beneath the sign of total break in order and history. (It forgets that riots are not an exception to civil society. They are its necessary product.) So in Europe, this arrangement of social upheaval, destruction, and lingering smoke gets called apocalyptic. But when that same mode of looking moves South, towards, say, sub-Saharan Africa, it just gets called Wednesday. It is read as quotidian recurrence, a general condition, neither an emergency nor a break.

Indeed, when the term does occasionally gets linked to images of sub-Saharan Africa, or other zones often considered "lost causes" (and hence as entirely beyond the scope of apocalypse's judging function), it does so in terms of spectacles that align clearly either with certain privileged concerns of the North, such as the destruction of wildlife as nature distinct from social history,

Photo by Nick Brandt, who speaks about the impetus of his work in terms of how, "Elephants are being wiped out at a rate of 35,000 a year. It's not hyperbole to say that it's an apocalypse of destruction.”

Photo by Nick Brandt, who speaks about the impetus of his work in terms of how, "Elephants are being wiped out at a rate of 35,000 a year. It's not hyperbole to say that it's an apocalypse of destruction.” That's the situation with Agbogbloshie, an e-waste burning and salvage yard in Ghana nicknamed “Sodom and Gomorrah” by those in the area. The site has captured the attention of northern media in recent years, largely, we can be assured, for the ugly reason that it photographs “well.”

Photos by Pieter Hugo

If you look at a wider range of photos taken of the area (especially those by Pieter Hugo, a South African photographer whose book and exhibition of Agbogbloshie photographs is called Permanent Error), it becomes quickly clear just how specific this mix of flat light, muted palette is while still oddly universal in terms of "apocalyptic" images, . The soil is always very dark brown, edging toward charcoal, or ashen. The sky is that now familiar white-grey. Others push even further in this direction, with more blatant after-work: in this image by Kevin McElvaney, the color is openly washed out.

[The composition also becomes familiar across the images of the site, especially those that read more as portraits: an often centered and mid-ground staging of figures in front of from the smoke and activity behind them, with a centered horizon line. It further echoes that form of solitary landscape contemplation seen in the films and posters included above.

In short, it's always noon on a cloudy day. Yet this simply isn't the case across the board. If we look at other photographs...

... the sky is blue, shadows are long, and dirt is brown.

I'm not interested in passing judgment about this decision, however conscious or not, to seek out or produce a certain quality of light.

The resonance goes even deeper, because the thing getting explicitly labelled apocalyptic in Agbogbloshie is neither the nearly unthinkable toxicity of the work nor the obvious echo of this wastescape amongst global depictions of hell. No, it is the montage of the cast-out: computer monitors, hard drives, DVD players, camcorders, all the hardware of digital storage and capture and creation. Not just a mass of images that circulate through such devices, these photos are images of digital circulation as a now-useless hoard, the cracked tail end of a commodity chain, as products of exchange and “immaterial” use are hammered apart and melted down in the most material possible, stripped for whatever final remnants of value stay hardwired within them.

A bridge made of computer monitors, Agbogbloshie

The apocalyptic here is not a measure of the impossibility of life in such a landscape but the "impossible" transformation of the hardware that the generic, and perhaps specific, we who look at these photos had saved for, bought on credit, lugged around, Tweeted on, wrote essays with, almost dropped, home-sex-taped-with, did drop, lived beside for years, swore at, listened through, got used to. In Agbogbloshie these things join together and are destroyed, indifferent to origin or purpose or who wrote what with what or on what screen we saw what photo that saw us at our weakest and we hesitated over it, putting in the trash before taking it out and hiding it in another folder. All that ends up as just the faintest trace of exchangeable value that can barely support the life of a community dying from such work, poisoned by the cancer-in-waiting that are these things we write with, pose for, talk to. Glass stared through for hundreds and hundreds of hours becomes something maybe worth stripping and probably stout enough to be walked on.

Between memories of one's computer and that computer's memory, what remains is a puddle of molten copper and sores that don't heal on the body of someone who isn't you.

From a liberal perspective, though, this social relation amongst the inanimate – the burning mound of hard drives, the bridge of old monitors – can only belong to a different social order in full, some unmoored fragment of history before or after capitalism, a lost cartography on the wing. As in: well, the circuits must be burned for heat, because the sun has gone out and the Eurozone has gone to shit, or they are being melted down because there is no more electricity so routers are being pounded into plowshares or... Pieter Hugo's gallery, Michael Stevenson, plays on this explicitly:

"There are elements in the images that fast-forward us to an apocalyptic end of the world as we know it, yet the alchemy on this site and the strolling cows recall a pastoral existence that rewinds our minds to a medieval setting."

And on and on, insisting that it is not an image of this age, this order.

But, of course, it is, unmistakeably so. It's just the last twist of the ordinary circuit of capital that never actually comes to a stop, not even when the commodity has "transferred all its value." As we know well, it just goes South, flung further out and away from its sites of consumption as materials and embedded time get leeched out in decreasing returns. Because umping grounds are just way-stations, however informal. The days and bodies of humans are still far cheaper than any automation, provided money knows where to look. And it always has.

Of the designation apocalyptic, this final element – the arrangement of stuff in a way that belief in progressive capitalist order can only comprehend as belonging to another time altogether – also lies at the quite literal center of the Kiev scenes and why received that description: the barricades made of tires, wood, wire, vehicles, municipal furniture, trash cans, trash cans on fire, penguin statues (see above photo), and, above all, lots and lots of snow and ice. Like the e-waste mounds, it's a montage of circulation gone wrong – at least, depending on one's perspective – as otherwise “neutral” and quotidian goods turn askew and elements of the regular flows of bodies, goods, and waste pile up, here in order to restrict and channel those flows against their continued invisibility. (An unblocked road is not seen, merely driven on.)

The loop of "misuse" is smaller in Maidan than Agbogbloshie, not a bonfire at the end of supply chains but the economy of traffic and infrastructure in one city, here packed tight into itself because of reasons concerning traffic and flows between that city and its country, that country and Europe, Europe as a failing concept and Europe as a mosaic of contiguous territories. In this way, and like the e-waste dump, it too is a dense compression of empire's reaches, wide geopolitical circuits and crammed into single sites, streets, squares, and fields – and, from there, into an image of that Empire choking on a piece of itself. The function of photographic image production, then, is to parcel this messy mass onto into a host of individual images to be seen on screens. They are a set of frames even more densely cluttered with anonymous materials, yet for all this, they are essentially multiples, interchangeable. Variation on a burning trashcan.

In those flat but textured images, the materials of this "apocalyptic" scenario becomes just so much catastrophic chaff, dazzling but impermanent, arranged for a specific purpose (a riot, work to survive...) but never intended to become permanent, merely piled up and frozen into place to be torn down or melted apart.

In Maidan, this was amplified all the more by the fact (and attendant images) of real freezing, as the barricades – and pretty much everything – were sometimes covered with thick patina of ice. In a comic and brilliant form of this, water was sprayed onto the ground to become an accidental rink for the riot cops to cross at their own peril. (AKA: Maidan – the Home Alone of nationalist urban uprisings.)

In others, as in the photos above, it bound things together: not like bricks and mortar, but a clear glue that lasts only as long as winter. Like the glass of shop windows, it presents those sheen combinations, whether willful barricade or things that just got left too close together, as what at once cannot be altered but cannot be made permanent, always ready to be unfrozen for the next arrangement. Put back where it belongs, hauled off to the dump, taken home, pushed to the side.

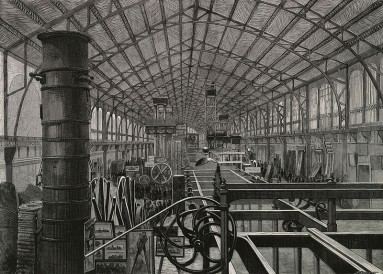

In that way, these ice barricades are an odd inversion of one of the more famed and critically trod elements of modern cities: the glass and iron arcades with which Walter Benjamin went notoriously wild. These too constructed a montaged compression of Empire’s reach – quite directly, given that Passage du Caire, one of first arcades built in Paris, was built to celebrated Napoleon’s return from Egypt.

Architecturally, that reach is frozen into a single, fixed, yet non-monumental space, one where the building is arranged with the dictates of giving space to see the variable and inconstant.In the arcades, the recent possibilities of glass and ferrous architecture were used to the ends of arguably the first architecture with no innate dictate of form other than the image of circulation – rather than an open-air market, for instance, where goods are on display but not behind glass, and where seeing, smelling, selecting, and purchasing them happen in the same spot or rather than a store where one enters in. Yet this peculiar quality of fixed yet temporary was already present in the very materials used, especially iron, which was taken first...

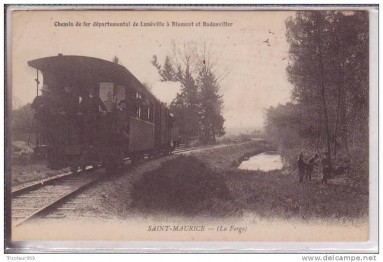

from railroads - the infrastructural permanence that allows for transfer of what carries its own energy -

La galerie des machines françaises, dans le Palais du Champ-de-Mars

and then from “transitory” buildings not intended to remain (exhibition halls, for instance).

The arcades join these two into an skeleton within which as much as possible is a window frame, an excuse for glass. This develops a screen in space, a screen behind which the transitory contents, brought from afar or "locally sourced," so to speak, can be changed without altering the space within which one moves. It's the architectural equivalent of the "prophylactic" defense mechanism - having a "blasé" attitude, that is – that Simmel identifies a full century later as the defense mechanism engendered by the "modern" metropolis. It is also the start of a very peculiar version of the built world that has become, over the last two centuries, not only diffuse but expected. One not just chock-full of screens, billboards, or posters as distinct entities, but one that structures all lived space as an arrangement of potential screens that at once display and divide and that gives the name apocalyptic to whatever is out of place and just in time.