Who shall say that man does see or hear? He is such a hive and swarm of parasites that it is doubtful whether his body is not more theirs than his, and whether he is anything but another kind of ant-heap after all. May not man himself become a sort of parasite upon the machines? An affectionate machine-tickling aphid?

- Samuel Butler, Erewhon, 1872

---

Until five years ago, I only had a couple of intimate and tactile relationships with glassy surfaces. The first began early, a symptom of growing up where winter is long but inconstant, with temperatures that climb and drop hard. Ice always appeared less a thing than a pause, a literal freeze-frame, because in Maine you don't get to step outside of the process. You don't go through winter piecemeal, always in a full circuit. First, there's the anticipation of snow, which can be huffed, a smell of dry in the throat's back, like smoke but from burning metal, not wood.

Then comes snow, sleet, tapering-off rain, slush, night’s black ice, partial melt, brown lumps of not-snow-but-not-ice, and then do it all over again, all on a long GIFish loop until you wake up and it's late April and outside, all the permafrost dog shit has come to light and nose.But when that pause happens fast enough, or with a slight interval of rain before night, you get the rare marvel of totally clear ice. We’d go skating, down the Royal River or out in the Cumberland marshes, where you could TIE Fighter swoop between the cattails and ash stands. I’d catch cracks and end up mouthing the milky pond, cutting my hands. Like an improbable crush or money, ice's surface always split this way, pitched between pleasure and damage, never more dangerous than when you don't realize you're already navigating it, when it's black on back roads.

When my grandmother's second husband died, she moved from Florida to live near us. I became newly, sharply aware of just how fragile we can be when crossing ice, especially when our bodies have already begun to bend like birds. All the same, I’d carry slick loafers in my backpack to school and put them on for the downhill walk home, to spend it slipping as much as possible, acting out a semi-skilled pratfall teetering on the edge of facial reconstruction.

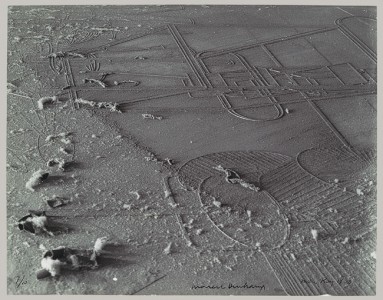

Man Ray's "Dust Breeding," 1920 photo of the back of Duchamps's The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)

Given that I don't wear glasses, my other memories of focus on, and care for, the smooth and unyielding are all about jobs. One was selling wine, where you spend so much of the day touching and holding glass. Stacking boxes of it, proffering $200 bottles of it to the rich like snake-oil.

For slick surfaces, the bottles gathered endless dust, or at least the dust appeared so visible because every speck violates an unspoken premise of wine fetishism. The wine can appear old, but only if it is wildly expensive, starts with Chateau, and conjurs cellar visions.

So all day I touched glass, but the glass was supposed to be invisible, only a problem – only visible – when too slick and itching to fall. It only worked when it could be ignored.

The other job with this surface experience was washing dishes at restaurants where I've cooked. It was the opposite of wine's glass. Washing makes you fixate on trying, as fast as possible, to get a surface back to looking like it was never used in the first place. (Or just close enough that your boss won't make you do it over.) This requires, and therefore develops, a strange hyper-sensitivity of fingers and palms, even as the heat, water, and bleach wreak havoc on hands, because you have to gauge without really looking: how much is still crusted on, how much texture there is to what is supposed to have none.

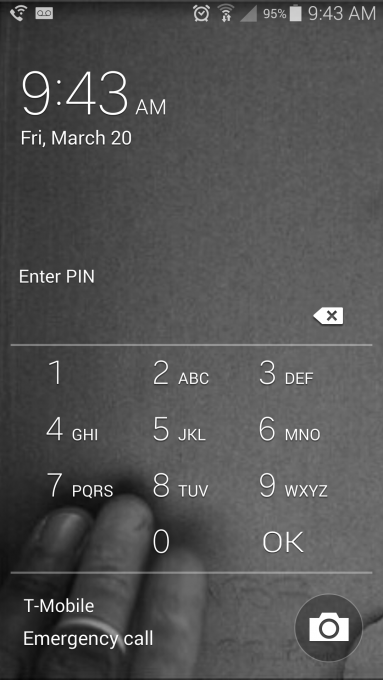

Until five years ago, these were the only times I had significant, affectively-thick tactile experiences with glass or the glassy. But five years ago, I got my first phone with a touchscreen. Now, like most people I know, I touch, rub, tap, worry, flick, and stroke glass at least once an hour, almost every hour that I am awake, almost every day of the year. My days, and whatever intimacy they include, are inseparable from the feel of something that shivers, as if touched with ice, yet always touches the same way back. I fell in love from afar, finger-skating fast filth on a Foxconned slab.

---

Fingers found in a Google Books scan of an 1848 fiction collection from Maine

I have zero interest in either bemoaning or celebrating this, because it makes no sense to me to think it in terms of good or bad.

There are, of course, other equally large shifts in humans' technical-social experience. The use of buttons, for instance, in the typewriter brought with it a widespread experience of language as mechanically input, one previously available only via the typesetter or the telegraph and hence still requiring an "expert's" mediation. The radio's simultaneity, both from source and site of listening and between those sites, between the car, bar, home, and farm. The mechanization of war. Cinema's animation of the still and reproduction of motion. The "whipping machine."

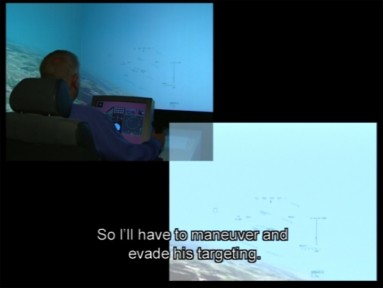

Harun Farocki, Eye/Machine II, 2002

Still, it seems right to assert that almost no other machine – not the phone itself but the set of gestures, textures, embedded memories and technical knowledge, metals and plastics, supply chains, work, and social forms that stitch together at the moment where it and I use each other – has so rapidly become inextricable from the everyday.

My interest doesn't lie in the general anthropological overhaul bound up with the digital, for which the phone has come to serve as one particularly visible index. I wouldn't know where to begin with that. Instead, I've become fixated on the sensation of a screen, on how it shifts from a sensational element in space – one that delimits the distance covered by projection or around which we gather – to a sensual object in itself. On how only a few years ago, I did not carry around a warm slab of receptive ice in my pocket but now don't need to look down to trace patterns into and via it. Even more simply, in the way that so many of us spend so much time petting slick and smeary surfaces, carrying windows in our ass pockets.

But with this whiplash recalibration of sight and hand, to find precedence of how it feels to not only touch but also to hold and carry screens, to care for them to the point that I don't think about them, I have to go back to what seems far from screens and their images, back to dishes, wine, and ice. Growing up with computers made a visual-practical relation to screens second nature, sure, but I learned to manually navigate Androids through winter and wages. Or through reading about Spinoza polishing lenses and realizing that even if there's only one substance, there's no reason that all of a body moves at the same speed. Or the way my friend polishes her glasses with a grey cloth when she's thinking or tired or both. The way that Tonya Harding fell and then wept, in spite of those gold blades. The way that Anna Kavan writes winter in Ice, running up against the limits of description and so just writing white and ice and frozen over and over again. How the security glass of bank windows require blows of different speeds and type. Malaparte's horses trapped in a lake's prison of ice. Hundertwasser's loopy, and totally correct, fantasy of cultivating mold on high-modernist glass houses.

And, to some degree, through watching and reading American sci-fi. Though not as much as to be expected, because the touchscreen has an odd history in the decades before it became ubiquitous.

Neuromancer

In William Gibson's first novels, ice (or "ICE," Intrusion Countermeasures Electronics) named the defense systems within cyberspace that had to be broken and evaded like frozen architecture, with the "worrying impression of solid fluidity" yet subject to becoming "the shards of a broken mirror."

Hackers, on the other hand, took that "endless neon city-scape" and gave it a Tron-ish literalism, depicting information as physical construction and vice versa, mainframes as glass towers between which hackers can zip and maneuver.

But in Hackers, as in the Gibson novels (and other strains of cyberpunk), the ice and glass remained either virtual or a metaphor-made-architecture. When it comes to the apparatus for navigating info cities or server farms, it is a console, something unwieldy and manual that the "jockey" must plug into in order to pilot cyberspace like a glider (Gibson). Or it's just a laptop you spray-painted with camo because you're so bad-ass you don't need to see what the keys say (Hackers and almost me, before I realized it was a terrible idea).

In the films I was watching in the '90s and '00s, ones actively concerned with feeling prescient, that split remained operative.

In Lawnmower Man (1992), the space is navigated from within the mind's eye, as the climax of experimental drug treatment and with slighter grander dreams – becoming pure energy in a mainframe, controlling the world, etc – than expanded emojis. If anything, the film is especially intrigued by the way that these experiences are never purely digital. The god-to-be is not defeated by Wing Chun with trenchcoats or a proto-Matrix peeking behind the veil – that is, not by struggles inside VR. Instead, they just blow up the building where the mainframe is housed.

Swordfish, 2001

And when excitement and budgets didn't get blown on CG to depict what the Internet looks in cross-section , they went instead for the virtuosity of managing multiple screens at once, via a generic hacker's keyboard flutter, as in Swordfish.

As for starships, they held to a vaguely pilot vibe. For all the advanced tech in Independence Day, the alien craft is piloted by something held – a tremendous metal joystick – and analog enough to be patched into by Goldblum's Dell. On TV shows, like Battlestar Galactica and Stargate SG-1, the screen-heavy spaces of the "bridge"/combat control room/etc continued to contain what one would expect:

Battlestar Galactica

Stargate SG-1

namely, keyboards and monitors as distinct things. One of the prime reasons seems to be that like the Kinetocsope, the touchscreen is an interface built for one, never particularly efficient where one might want to show someone else what's on the screen. ("As you can see, Commander, the enemy's ships are approaching from..." "Can you move your enormous hand? Jesus.")

There are, of course, exceptions. Star Trek: The Next Generation, for instance, got in on the touchscreen game early.

Total Recall, for instance, manages to envision something not just of Wii Tennis...

... but also, and more saliently, TSA screening lines. Yet in that screening scene, we notice that the keyboards of the future (just the desk itself) on which the agents clatter

By the time of the remake, 22 years later, phone and tablet lessons had been learned, and the film has become obsessed with this other possibility. Its screens are now a) indistinct from architecture and b) ready/eager to be touched, using the palm as one's biometric identification so that Colin Farrell can have Very Urgent Chats, a hand laid on the surface like the Plexiglass wall of a prison visiting room.

All in all, most of what I watched was uninterested in the feeling of screens. It was far more hyped about skipping over the messy fingerprint stage and going straight to the vaguely holographic, as if aware that there's something endlessly throwback and manual about drunk-smearing burrito fingers across Grindr.

Minority Report, 2002

Minority Report, 2002

And so, in Minority Report, not only does Tom Cruise not touch the screen. (The germs, he cries, the germs.) He also wears special gloves, data prophylactics that let him keep his distance. The screen becomes the wall, yet the wall ceases to be something we might rub up against: set in space, yes, but as immaterial as possible.

The Iron Man films go even further with this, arraying OS windows in the holographic air, letting you crumple up represented paper without even needing glass in the room.

That gets pushed to its extreme in what was the most stylistically innovative show on television, CSI: Miami, for which the entire precinct is a Constructivist upchuck by way of Lisa Frank, where the built and the screened look actually identical. I imagine Horatio walking into walls all day, mistaking them for browser windows and pastel lens flares. So while while the entire fantasy of the show is of unlimited forensics, where no image is too poor to not be "cleaned up" into magically high resolution, no trace to miniscule to not bind it back to a body, the screens themselves just hover, neon and pure, as free of smudge and splatter as the agents' white jeggings.

CSI: Cyber

CSI: Miami ended its gloriously protracted decade in 2012. CSI: Cyber has just started this year, and it's hard to say how long it will stick around.

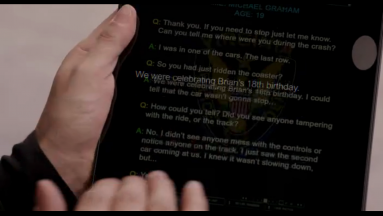

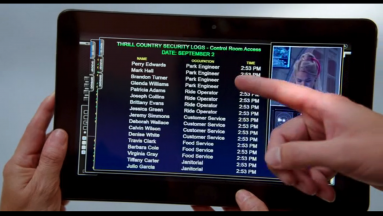

First, those that cannot be touched whatsover, as they exist only for the viewer, not for the character, in House of Cards-esque floating panels, as in the episode where they moralize massively against Uber (under the name "Zogo").

Second, in huge situation-room panels at the center of their office, where they can do military-grade FaceTime but, crucially, still control everything by the keyboards and mice at their desks.

Third, with so many hands, gesturing, tapping, pointing, and getting in each other's way. Sometimes these hands are part of shots that try and approximate what it feels like to be absorbed in a screen, like the camera rotating around a stationary Arquette, staring at her tablet while snippets of text and voice flutter about. Other times, it's just Van Der Beek – or a hand model – literally pointing our attention while explaining what a phishing scheme is. (Again, the show may not be long for this world.)

The same dynamic is also at work with more future-oriented shows and films. It's not until the real existing daily use of touchscreens by millions of people that sci-fi grudgingly hoists them into view. And when it does, it reserves them for restricted and obvious uses.

1. Phones of the near-future (same as regular, just a bit more translucent, like in Robot and Frank).

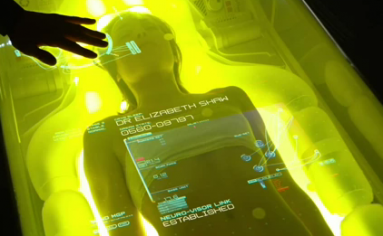

Prometheus, 2012

2. Proxy for the medico-erotic.

Oblivion, 2013

3. Domestic/military logistics (the cup of tea resting on the touchscreen control panel that monitors both a blighted earth and a glass-bottomed swimming pool). Indeed, it's that moment of screen-as-table that comes closest to the fantasy most of us really have about touchscreens. Not to have them vanish into space, not to become ever thinner until they wish themselves into immateriality, not to have them lilt bright around our heads, but to eat off them, to watch Hannibal through a vanishing mosaic of Hot Pockets and give the holographic Ghost of Commodity Future a very sloppy middle finger.

gesture/data, 2013 (Oil on flatscreen, VHS transferred to .mp4)

gesture/data, 2013 (Oil on flatscreen, VHS transferred to .mp4) ---

Both that urge – the slob screen – and the way in which most speculative films and TV tried to ignore it until it became unavoidably quotidian strikes me as telling, hinting toward an awkward proximity. For all the fantasies of the holographic and the talk of the immaterial, the fact remains that the digital stays rooted in the very physical, from the mining of rare earths to human mechanical turks, from the multiple hands of the compositor

They Live By Night, Nicholas Ray, 1948

Prior to touchscreen phones, there were probably only two significant interactions you could have with commodities through glass. You could go window shopping, entering a circuit of fantasy and denied fulfillment, becoming also an extension of the store itself, a flesh-and-blood ad's image of rapt yearning. Or you could go looting. Those are the options: find some potential pleasure in being blocked by the glass or stop being blocked by it.

https://youtu.be/rBW0EthzzCk?t=1m16s

It's in those terms that the opening of Joseph Lewis' Gun Crazy (1950) is so smart. There, the lens of the camera and the "lens" of the shop window double up without telling us, as we've taken our position behind the looking glass before the film makes this clear with a reverse shot from the boy's perspective. So the camera is already a security camera, opening up the possibility of not just the triangulation which psychoanalytical takes on cinema love so much – the apparatus, the gaze of the boy, the promise of the gun – but, much more importantly, the line of invisible demarcation that's supposed to keep the gun on "our" side, the poor safely on the other. As is often the case, at least in actual history, it takes a rock to make it obvious where things stand, a rock to make clear that surveillance doesn't stop when you turn your back on it.

Screen blood

With touchscreens, a new operation is possible: one can activate commodities, be they in-game powerups or Amazonian toilet paper, by pushing on another commodity layered with alkali-aluminosilicate glass, by pressing your face to the window.

Shards (in ad for repairing a screen built too fragile from the start)

Of course, the reasons not to replace screens are plentiful and obvious – mostly, that these things are so expensive to start, and few people can afford to put even more money toward them, even if they come to feel like a necessary element of how one navigates every day. Nevertheless, I've watched people embed shards and splinters of glass in their fingers, tiny motes of blood coming to the surface, because they keep swiping across a shattered surface that holds the cuts in place, bleeding because they had to reduce their pet's stress level in Kawaii Pet Megu. When I smashed the hell out of my phone's screen,

1928

Near the beginning of Alexander Kluge and Oscar Negt's gargantuan, sprawling, and genuinely brilliant History and Obstinacy,

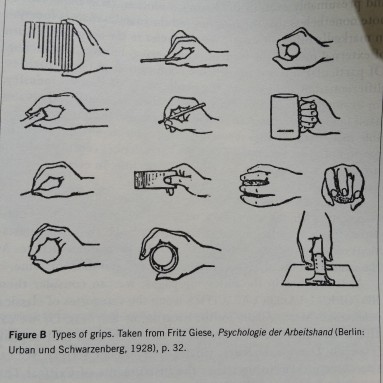

"Of all the characteristics responsible for unifying the muscles and nerves, the brain, as well as the skin associatively with one another – in other words, for the human body's feedback systems, its so-called rear view [Rücksicht] – the ability to distinguish between when to use power grips and precisions grips is the most significant evolutionary achievement. It is the foundation of our ability to maneuver ourselves, an ability that is most easily disrupted by external forces. These forces are also capable of disturbing our self-regulation. Self-regulation is the outcome of a dialectic between power grips and precision grips." (p. 89)

With touchscreens, we grapple with a new language of gestures imposed wholly by external forces, gestures that signify only insofar as they are registered in code. But perhaps the strangest of these isn't one bound up with the software, neither the erotic indifference of the left swipe or the fact that, in a rather generous act of anti-planning, the swipe-to-text function of my current phone obstinately avoids predictively spelling TOMORROW, offering instead TIMEPIECES, TINTYPE, TIPTOES, and TIMELESSNESS. No, the gesture that seems so alien to me, alien in just how natural it has become, is the maneuver of the sliding grip, a delicate oscillation between power and precision. Because despite being held by hands, iPhones and their competitors were never designed to be held. They are designed to be naked screens. Screens without hardware, ghost screens, guillotine-blade screens. They are only allowed to be held grudgingly, as a last resort, and we slowly fool ourselves into imagining that these sharp panes of ice feel good in the hand, let alone stable. But how do we hold something that isn't supposed to be held, whose entire front is intended to be as smooth as possible? What would it be to grip a screen that's only as thick as its image?

And so aside from learning how to type and swipe, we learn also that particular move of gripping glass while letting it slide. In bed, trying not to wake someone sleeping on our chest, we grope far out in the dark until we just barely feel that familiar smooth chunk, marked by feeling like nothing much at all. We slide it toward us with a minor flick of the middle finger, then pry it up between the thumb and forefinger, drawing the hand toward us with a gentle wrist's whip, so that the phone is both held and turns. It rotates over a breakable fall, pinioned without screws by finger's oils, and comes to rest in the palm. Then we look and see that it is still night and that a bot named "silkfeather_92" liked a photo we took and that in the dialectic between power grips and precision grips, there are no winners.

2015

That grip, a variety of which is also used when we pinch-draw the phone from a pocket and throw-slide it into the hand, is not just a grip. It is also a gesture, which to me means that it doesn't signify or supplement anything. Rather, it stands uneasily between language and action, speaking of the limits of the former to make itself heard and the refusal of the latter to stop trying.

If you asked me to say to you a list of all the words I know, I'd probably have the experience of knowing that there are words I've read, wrote, and said but that I simply cannot call to mind for the list, that I don't remember that I know. In order to explain this to you, though, I would have to use words, and, in so doing, likely stumble onto some of the words I'd forgotten.

Perhaps that's how it is with our hands of glass. To draw a balance sheet of what we've lost and gained, what forms of touch have been displaced or enhanced or scrapped because we can't keep our hands off ice screens, we could only do so through moving our hands, passing them over things, tilting slabs, seeing what happens, what registers, what remembers. But being gestures, they can't say or do anything other than depict the contours of the systems within which they might communicate, amongst ourselves and between our devices. From what I've read, it seems that those who design and manufacture these things, those who mine rare earths and seep thorium into water supplies those who drive workers to suicide – that is to say, we, we who are inseparable from these things – keep yearning for tougher and tougher glass, be it Gorilla or sapphire. The endpoint of that dream can only be a glass so hard that it could only be marked as ever having been touched by more of that glass itself. If that's the case, at least I'll finally know how to write TOMORROW on my phone.