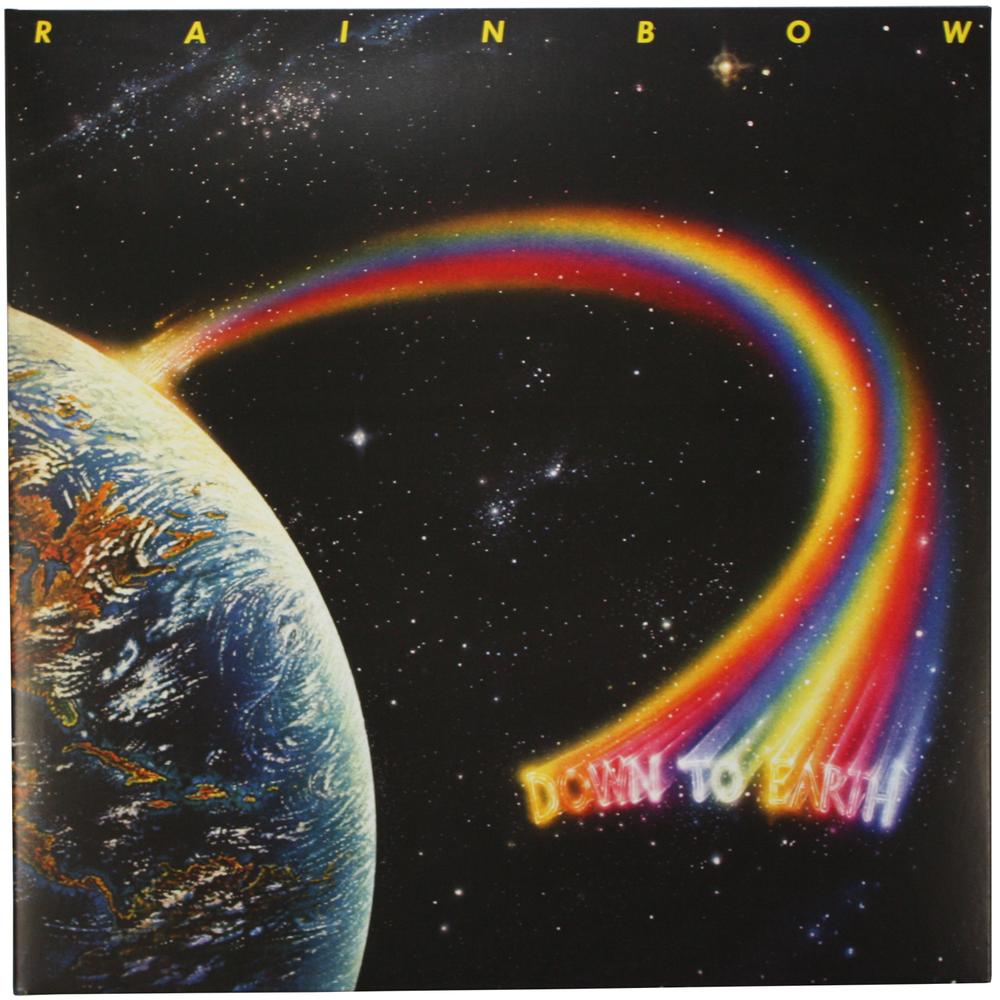

The rainbow as a symbol of gay pride dates to 1978, when a flag made by Gilbert Baker was flown at a march in San Francisco and was widely adopted as a symbol of solidarity after the assassination of Harvey Milk later that year. The band Rainbow dates to 1975, when guitarist Ritchie Blackmore became fed up with the image and musical direction new members David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes had brought to his band Deep Purple — lumbering hard rock-funk fusion; cliched, cocaine-fueled macho posturing — and broke away to form a new group with vocalist Ronnie James Dio.

One might have expected Blackmore to be chagrined when "rainbow" began to be associated with a different sort of audience than what is usually thought of for his music. But let's not forget that Deep Purple's crowning achievement was an album called Machine Head. Rather than shy away from the rising connotations of the rainbow as a marker of gay culture and affiliation, Blackmore responded in 1979 by releasing Down to Earth, one of the gayest albums in the hard rock canon, rivaling even Judas Priest's Hell Bent for Leather in its willingness to explore homosexual desire within the deeply homosocial context of metal music. A tour de force of innuendo, coded language, frustrated desire, and orgasmic musical release, Down to Earth is not merely promiscuously available to the ministrations and interpretations of queer theoretical analysis; it is so dense with gay textuality that it might profitably be considered a work of queer theory in its own right.

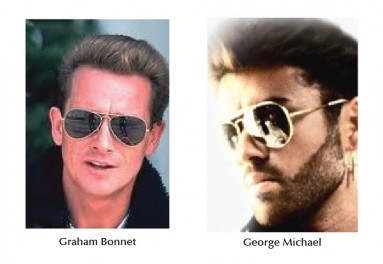

For Down to Earth, Blackmore decided to replace Dio with Graham Bonnet, who was something of a departure from the swords-and-sorcery, rock-and-roll-wizard image Dio had cultivated. Bonnet, an R&B singer who had achieved limited success covering songs written by the Bee Gees, had a look that was a cross between a Halfordesque leather boy with a penchant for aviator sunglasses and a softer, feminized male model out of International Male. Faith-era George Michael seems to owe a bit of a debt to Bonnet.

The startling conceptual departure that Bonnet marked merely through his physical appearance should have been sufficient to alert Rainbow fans to a shift in the band's intellectual concerns — there would be no songs about tarot cards or warlocks here — but if that wasn't enough, a song like "Love's No Friend" left no room for doubt. As the song's title suggests, "Love's No Friend" is an interrogation of heteronormative narratives in the culture and the pervasive damage they inflict by forbidding the expression of alternative forms of desire, whether they are same-sex or outside the couple form. The lyrics make plain their intentional queerness: "I've learned to live with a cloud above my head," the singer declares, and then evokes two key concepts in the enunication of gay struggle: "Got no shame, got no pride."

The pain of exclusion presents gay subjectivity with a paradox: being cast to the margins allows one to act without shame, though without cultural recognition or validation. The tension between these two poles suspend the gay subject in a detrimental equilibrium. "Got no feelings left inside," Bonnet moans, with a passion that obviously belies the meaning of the words. The song preaches defiance — "Ain't gonna fall for no line," the singer cries — but Blackmore's melancholy, minor-key soloing undercuts it, suggesting it is at best a partial solution. One cannot reject heteronormativity at the level of the individual; its hegemony deforms the subject beyond the reach of the conscious will. To correct the deformity would require a change in the entire drift of society.

The other tracks on Down to Earth take up various facets of that challenge, exploding the tropes and anxieties of straight masculinity and positing challenging alternatives to it, as in "Danger Zone." Again, the lyrical intent of this tough cruising anthem is not exactly obscure:

Love don't make it on those pin-striped nights

When you're looking through someone's disguise

You can't make it alone, so you gotta make a move

But you're looking at nobody's eyes

The chorus then ambiguously asserts that "love don't go begging in the danger zone." The idea here is that "love" in the sense of sexual activity can easily be found in the cruising "danger zones" of the pre-HIV 1970s, but at the same time it would be a mistake to name it "love" -- love doesn't go there, and its ideologized comforts won't be found. You will not find a self-stabilizing relation; instead it is a place where normative gender relations and the straitjacket of sexual orientation evaporate (your own eyes become "nobody's"), and you will learn that, as the song states, "faking has no return."

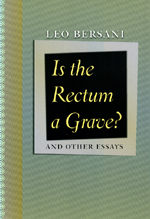

Here, then, we are deep in the "danger zone" of jouissance, as Leo Bersani would later describe in "Is the Rectum a Grave?"

Male homosexuality advertises the risk of the sexual itself as the risk of self- dismissal, of losing sight of the self, and in so doing it proposes and dangerously represents jouissance as a mode of ascesis.

So the danger zone — really a sexual counterpublic, in Michael Warner's sense — is dangerous only to the extent one is attached to the self as such and that which anchors it in patriarchal society, the gendered power relations that hinge on viewing passivity and penetration as sexualized violence. The danger zone is as dangerous to social control as it is supposed to be to self-control.

The other tracks on Down to Earth are not as overt in their queer themes, but they are unmistakable once one begins to listen for them. The album's opening song, "All Night Long" at first blush seems full of standard numbskull cock-rock bluster. But it turns out that this exaggerated parody of straight desire is displaced aggression, a response to how that desire always threatens to dissolve into a puddle of anxiety. The singer keeps insisting, "I want to love you all night long!" but the very insistence of the demand transforms it into a plea: Give me the sexual capacity to go all night long, let me escape the trajectory of straight male desire and its deadening refractory periods, let me become like a "girl who can keep her head, all night long."

Such capacity is theoretically available with a willingness to be penetrated, but as Bersani notes, "To be penetrated is to abdicate power." Thus that furtive desire to become feminized, with an insatiable capacity for pleasure, must be buried under derogatory sexist comments: "I don't know about your mind but you look all right"; "Your mouth is open but I don't wanna hear you say goodnight." This sexism is the price for maintaining the heterosexual couple, as Warner and Berlant put it in "Sex in Public,"the referent or the privileged example of sexual culture." It is a gender-inflected expression of what Bersani calls "sex as self-hyperbole," a self-aggrandizement to stave off the way desire threatens to shatter identity.

If "All Night Long" is about the trap of masculine phallocentrism, the album's hit, "Since You Been Gone," is about homosexual panic, about a fear of, and desire for, the closet.

Its bridge addresses the closet directly ("These four walls are closing in, look at the fix you've put me in"), which clues listeners in to how "you" stands for both his gay desire, alienated as a invading entity, and for debilitating protection the closet affords. Without its protection, the singer admits he has "been out of my head, can't take it." But there is no alternative; desire has already fractured his pretense to hetero identity: "I get the same old dreams same time every night, fall to the ground and I wake up." The dream of becoming a "bottom" hinted at in "falling to the ground" is not something the singer can elude. "You cast a spell, so break it," he implores, looking for a release, but there is no escape.

So in the night I stand beneath the backstreet light

I read the words that you sent to me

I can take the afternoon, the nighttime comes around too soon

When night comes, disruptive desire reasserts itself and language is useless for dismantling it. Incapable of coming out, yet incapable of not acting on this desire, caught between homo/hetero, the singer is driven beyond epistemology (his conflicted desires render him "out of my head") and representation.

But the album's centerpiece is "Makin' Love," which not coincidentally would become the name of a groundbreaking American film about a married man having a homosexual affair. The song's lyrics tie together the disparate theoretical ideas of the album in one tightly wrought chorus.

How can I deny my heart

When my love is blind

I got no choice

I've gone too far

I lose my mind

When we're makin' love

Here, the singer admits to a "blind" passion beyond sociocultural categories that carries him "too far," past the will to normativity. This desire, he confesses, will cause him to lose his mind, forgo subjectivity and admit the "internalized phallic male as an infinitely loved object of sacrifice," to borrow Bersani's phrase. "When I look into your magic eyes, the mirror of my love," he sings, openly acknowledging mimetic desire rendered sexual, and the urge to shatter that mirror in an act that's equally transgressive and unnervingly familiar.

Though Down to Earth was among the band's higher-charting records, overt queer theorizing at this level of sophistication was somewhat over the Rainbow. Bonnet would leave the band after this album, to be replaced by Joe Lynn Turner, an anodyne Lou Gramm clone, as Blackmore would try to steer his band toward conventional MOR success. Instead of continuing to chart the course of radical intervention in the name of queer culture building, gay fans of the band were abandoned, left to walk the Street of Dreams.