The following is a guest post by Linnéa Hussein.

It's called Slumdog Industrial Millionaire and the Ecstasy of Victoria. Not even the Nazis could top this shit.

—Danny Boyle on the Opening Ceremony, "Fuck the Olympics" in If You Can Read This You're Lying

During the Olympic opening ceremony I sat outside in a beer garden in Germany trying to have a conversation with an old friend, when my visiting friend from Luxembourg kept pointing at the television screen behind the windows mumbling about Britain’s idiotic ways of spending money and distorting their history. That was my first glimpse at the Olympic Summer Games 2012: a muted screen full of bizarrely arranged Mary Poppins, Shakespeares, steelworkers, and 007. I didn’t think much of it until I came home and saw the flood of enthusiasm and national pride on Facebook coming from my British friends. No matter their socioeconomic background or the fact that some of them had trouble finding work in credit crunch times, I heard exclusive voices posting things like “proud to be British,” “fantastic opening show,” or “good job, Danny Boyle.”

As far as sports go I couldn’t care less. I am a film person. As a rule, sports and I are diametrically opposed. I always thought the University of East Anglia, where I studied as an undergrad, had it right: the only department that scheduled classes on Wednesday afternoons when all sports activities were happening on campus was FTV, the school of Film and Television Studies. Since the main focus of my work usually consists of colonial depictions of an empire and the distorted mapping of a world that was artificially created to convince its habitants of its authenticity, I do find there is something to be said about Britain’s opening night from a perspective that is neither British nor sports-friendly.

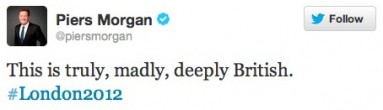

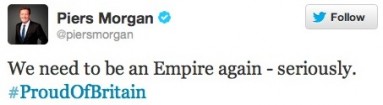

The question that wouldn’t leave my mind the night I saw all the Facebook posts was, "Is this what people mean when they talk about healthy nationalism?" How can a nationalism be healthy if it means turning a blind eye to (in this case) rising unemployment, racism, not to mention centuries of colonialism, abuse, and torture ? Piers Morgan went as far as to use the hashtag #ProudOfBritain to advocate empire. With all this great pride in the nation, where are the rioters hiding that were so sick and tired of the nation and its dusty conservative government that whole neighborhoods were burning this time last year?

I am from Germany, a country that resents itself so much no one would ever dare to like it out loud. The burden of having initiated not only one, but two World Wars is all that it took for generations to come to bow their heads when it comes to national pride. In Escape from Freedom, Eric Fromm explains Germany’s attraction to fascism after WWI as an interest of the people to create a new order within the state to be able to be proud of their nation again†

The only loophole for Germans to be proud has always been sports. Sports seem to have a right for a different, more radical rhetoric when it comes to nationalism. In 1954 Germany experienced the “Wunder von Bern” or the "Bern miracle" when we won the World Cup. “Deutschland war wieder jemand”: Germany was somebody again. If we cannot be proud of our political history at least we can be proud of our soccer players. By “we” of course I meant the German nation as a whole. As I will get to later you will notice that Germans do not often get the chance to express positivity regarding history, and if “we” do, it’s most likely in sports. As a “child with an immigration background” (as they call me officially over here) I usually don’t mind to be excluded from the second-person plural used in regards to the nation, but I feel it is safe to say that sports offer an opportunity to use it out in the open and enjoy a hunch of happy camaraderie every now and then.

For me, the first time Germans visibly began to show flag again was yet another sports event: the World Cup of 2006. We didn’t win, Italy did. But we had what the media called our “Sommermärchen,” our summer fairy tale. The young national team was supported everywhere you went. Flags outside of houses, flags outside of cars, car mirror covers, shirts, pants, bandanas, you name it, black, red and gold as far as your eyes could see. Even my own mother bought a pair of Adidas Germany flip-flops on sale to sport them at the pool in Portugal, where we spent our summer holiday that year. I had already moved to England and was just with my family for the summer. The flood of flags felt weird and creepy for quite some time at first. Partly it felt like people were enjoying 'breaking the law’—you have to imagine the feeling as if one by one people started to wear swastikas and that after a while wearing swastikas was OK because everyone wears them again. As fascinated as I was by the sudden outbreak of a united national happiness, I hesitated to borrow my mother’s shoes as I could still hear the words of my politics teacher ringing in my head. I had trouble differentiating between the flag and swastikas and I couldn’t help but wonder: what gives football the authority to change the unspoken laws on showing the flag that are still in place off-season?

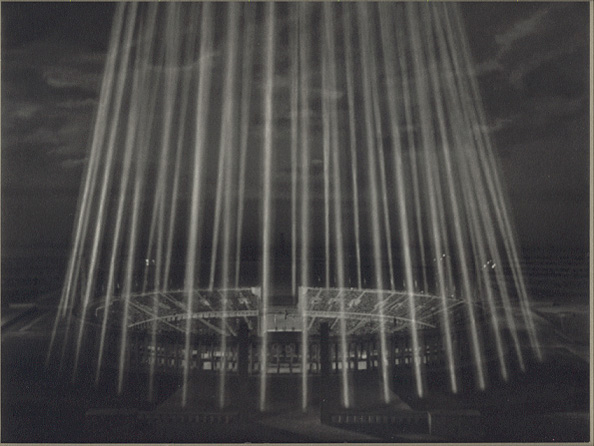

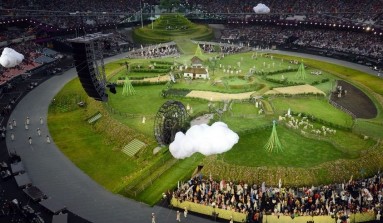

The Brits called their opening night Isles of Wonder, but the spectacle that was reminiscent of a Busby Berkeley musical of the 1940s didn’t differentiate between sports and history the way Germans do.

From my experience, the word “history” itself has negative connotations in Germany. History, as a subject in school, is something you learn a lesson from. Something you are making better than your ancestors. You don’t learn much about history that makes you proud. From witch-hunts to crusades, from WWI to WWII you have a brief period of the golden 1920s that then again is overshadowed by the arrival of the Nazis. The Holocaust takes up most history lessons between grade 5 and 13 and there is hardly any space for Germany post 1945, and the little there is, is spent on partition, not on the economic boom of the 1960s or other positive events. It’s like a visit to the German History Museum in Berlin. By the time you finished viewing the WWII exhibit on the second floor, the museum is already closing and you have to come back another day to see what happened after the war.

When looking at the history curriculum in Britain, it seems like the country is also willing to address its dejected pasts. However, the lens through which Danny Boyle presented the nation’s Isles of Wonder puts all of that knowledge neatly aside and focuses on the good. As questionably as Slumdog Millionaire reflected the reality of poor Indian youth, the opening ceremony of the Olympics distorted the image of a country that was burning just one year ago and whose economy is yet waiting to cool off.

I mentioned Busby Berkeley earlier. His spectacular musicals also arrived at a time when people escaped to the movies to avoid seeing their city burning. But unlike Berkeley Boyle did not merely create a spectacle full of attractions to distract from the consequences of the credit crunch. He chose to present history. For me, it is one thing and actually, a nice thing, to celebrate a country’s achievement through its cultural heroes. Shakespeare and Charles Dickens have indeed enriched the world that was invited as guests to the Olympics. Yet creating a British medieval agricultural wonderland, which then transforms into a steel mine and the heart of the Industrial Revolution that lays the base for the technological advancements made by Brits skips basically most chapters of British history (slavery, absolutism, colonialism, and imperialism to name a few) by which means the nation gained its prosperity in the first place.

For a country that first and foremost was attractive for me to live in because of its vast multicultural body, a shattered crappy looking ship full of the first Indian immigrants during the show does doesn’t exactly help to get rid of the stereotype of the immigrant that still dresses in turn-of-the-century clothes, has a thick accent, and will never be able to have a real job. By accentuating the arrival of the foreigners instead of embedding their presence as part of the other highlights, the Other keeps his visitor status.

Maybe the broadcasters figured there would be no audience for the re-enactment of the British slave trade, imperial torture, or people losing their jobs en masse. Yet I think it is dangerous to spin a country’s history into a fairy tale for the sake of entertainment. Paying tribute to the NHS, one of the true achievements of British history, is great, but it leaves a bittersweet stain with the knowledge that the government is in the process of privatizing it. I could imagine Germany parading around Goethe, Freud, Bauhaus artists, or the Brothers Grimm, but I am sure the world would not be very forgiving if Germany created a ceremony around its glorious historical achievements leaving out the nasty bits. Boyle’s attempt to show history from the workers’ perspective is honorable, however, the fake socialist presentation of a people that came from nothing but fields and turned the poor country life into an empire by standing on their own feet is simply fallacious.

I don’t know if I will ever be able to experience nationalism without feeling a little too far to the right. Opening night was meant to be grand, just like the Queen’s jubilee two months prior to that. Why not giving the unemployed and bitter people a sparkling night to cheer them up? As an expatriate, who has spent several years living in the UK and the US, I was always fascinated by the lightness of loving one’s country and being able to see it with kids’ eyes through rainbow glasses. I remember my brother and I escaping the rain at my sister’s seemingly endless graduation celebration at Harvard University and how shocked we were that though inside, people were still standing up in front of the screen to sing the national anthem. Nevertheless, there was a little jealousy. Up to this day, I don’t even know all the words of the German national anthem. Maybe that is the raw source of my criticism, the jealousy stemming from the inequality that I was denied in possessing a nationality or nationalism. In addition to the German guilt there wasn’t much about being Arab to be proud of either when growing up. In pre-9/11 education materials, Arabs appeared as mean pharaohs that kill Hebrew babies or Saudis that denied Americans gasoline during the 1973 oil crisis. After 9/11 more history about Arabs got filtered into the books, but of course, the collective reputation was worse than that of pharaonic Egypt.

As for Germany’s reaction to the Olympics, the major TV stations ARD and ZDF decided to program two films this past week to remind us of Germany’s Olympic legacies. The first one was Berlin ‘36, a drama about Gretel Bergmann, a Jewish high jumper who was bullied off the Olympic team in 1936 and replaced by Marie Kettler, a man the Nazis dressed up as a woman to get the Jewish girl out of the race. The other production was München ‘72, a feature length documentary about the Palestinian terrorists that kidnapped part of the Israeli team in the 1972 Olympics. Both films showed very grim chapters of German history. However, at the risk of sounding nationalistic, I was a lot more comfortable watching those films than watching the opening ceremony in London.