Turning on the charm used to mean something quite different

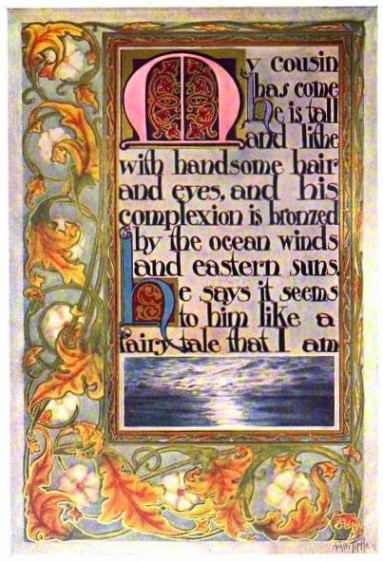

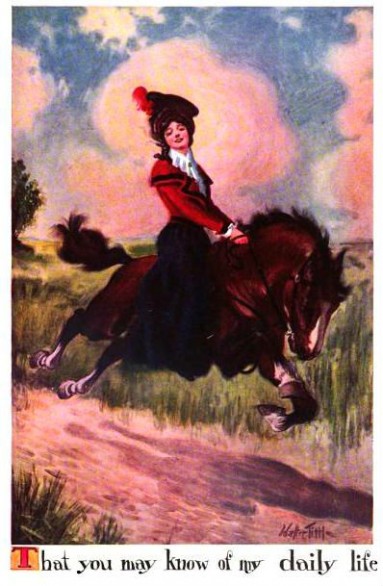

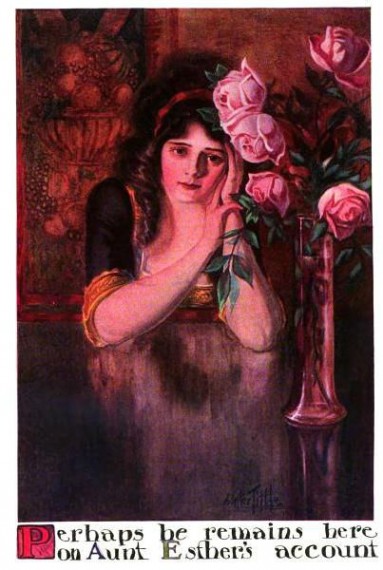

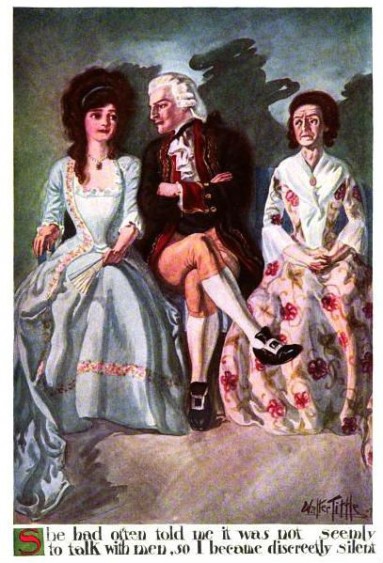

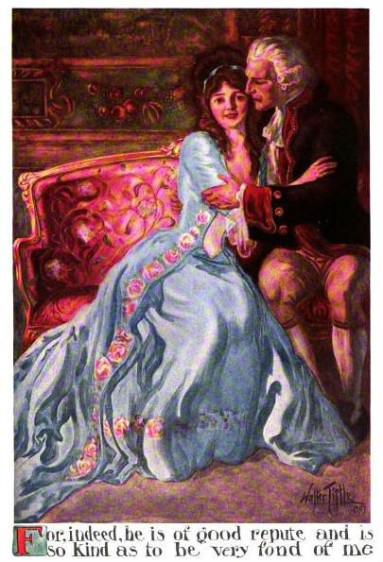

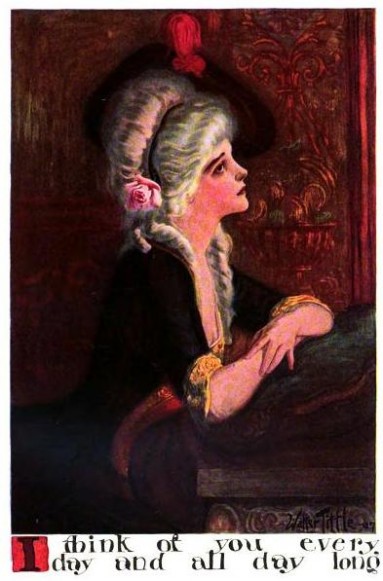

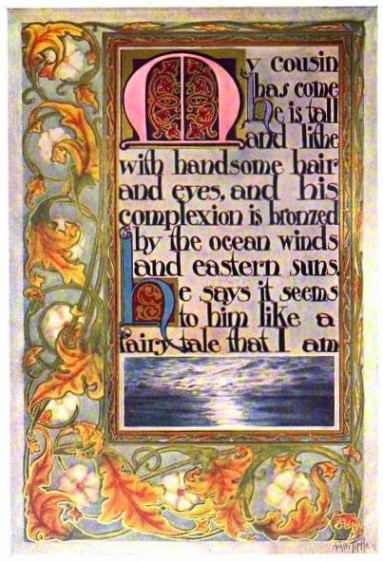

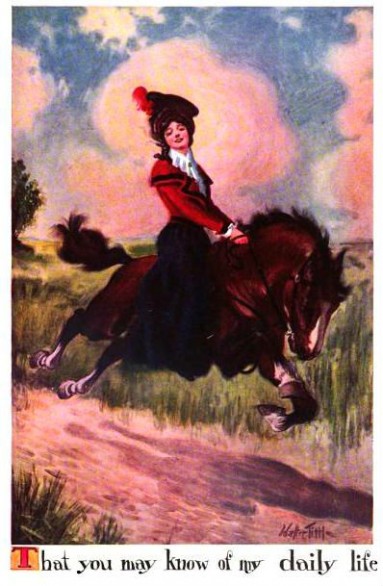

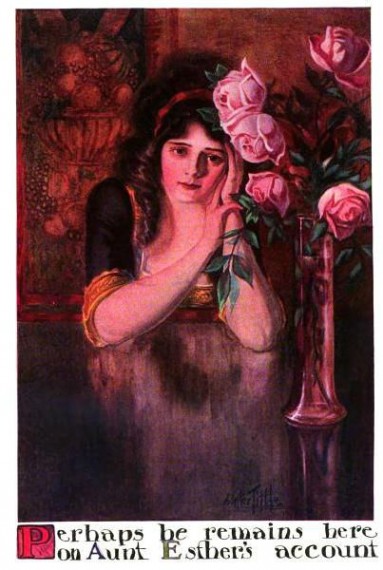

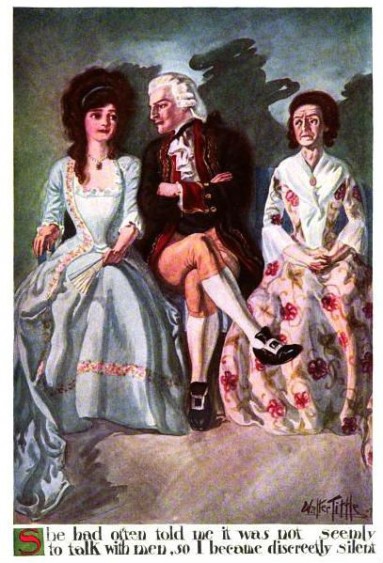

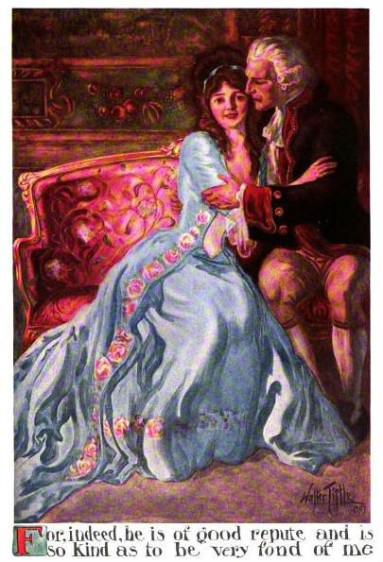

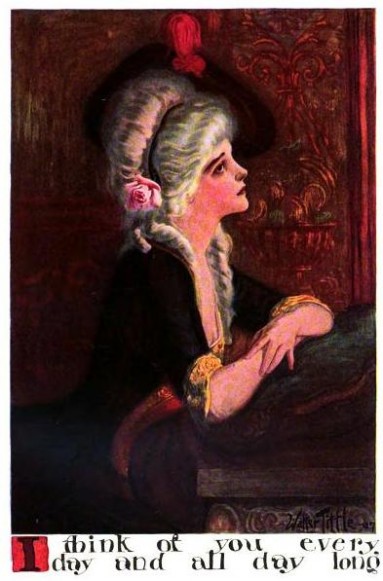

Illustrations from The First Nantucket Tea Party (1907)

Whatever loneliness or boredom the workers of Salzburg's famous salt mines endured they eased with an unusual pastime. They would find a tree branch, strip away its leaves and toss it in an unused pit. Two or three months later they would haul it out and delight in its transformation. Every one of its twigs bejeweled with salt crystals, it appeared more a scepter of some elf king than any piece of forest litter. It and others like it the miners would hand to tourists, who marveled at the splendid gifts.

This transformation Stendhal attributed to a "brine which moistens the bough and then subsides and leaves it dry." Romantic crystallization takes place in an imaginary solution.

When in the summer of 1818 the French writer Stendhal visited the mines he too was captivated. That so ordinary an object could achieve such exquisite beauty fascinated him. Ever an astute and imaginative observer of life, he came to regard it as a metaphor for love's mysterious processes. "By the mechanism of the diamond-covered bough in the Salzburg," he concluded, "everything which is beautiful and sublime in the world forms part of the person we love."

"The hearts of pretty women are like bonbons, wrapped up in enigmas."--J. Petit Senn

Like the diamond-covered bough, the beloved never fails to delight. "It is as though by some strange freak of the heart," Stendhal writes, "the woman one loves communicates more charms than she herself possesses." Everything occasions thoughts of her exquisite, enduring perfection -- the way she bites an apple (those eye-teeth!), the way her her cheek reddens, the way her chin dimples. But where passion grows, so does risk. The beloved threatens always to withdraw, to leave her lover adrift. What then for the heart seized by crystallized affection? "Apart from ridicule," Stendhal warns, "love is always haunted by the despair of being abandoned by the beloved and of being left nothing but a

dead blank for the remainder of life."

"So great a happiness do I esteem it to be loved," proclaimed Xenophon, "that I fancy every blessing both from gods and men ready to descend spontaneously upon him who is loved."

"What will be the event of my love for Her?" asked Robert Browning before his marriage to Elizabeth. He consulted an Italian grammar, opening it at random, and his eyes alighted on a translation exercise. "If we love in the other world as we do in this," it read, "I shall love thee to eternity."

"Has some Thessalian poison bewitched ... my body, is / it come spell or drug that has brought this misery upon me. Has / some sorceress written ... my name on crimson wax, and stuck a pin in my liver." -- Ovid, Amores

It comes as no surprise then that against such devastating abandonment lovers took certain measures. History tells of love charms and philters, all promising to corral wayward objects of affection. Kings and queens used them, as did scullery maids and postal clerks. These charms were uniformly bizarre, involving apple pips pasted to foreheads and garters tied in knots as the wearer sang light verse while mincing freshly killed turtle doves and toads for stuffing in sheepskin. Hopeful admirers hid daisy roots under pillows and hung shoes out of windows. They danced under full moons and hid trinkets in the sand. They summoned spirits, skinned bats, and pounded teeth and bone to powder. No incantation, elixir or ritual went untried if it promised success.

"Isabelle was there from the land of meteors, of avalanches, of wrecks, of plunder. She had thrown me a word of liberation, a program; she was bringing me the invigorating breath of the North Sea." Violette Leduc, Thérèse and Isabelle (1966)

Trying these charms often required great fortitude. On St. Valentine's Eve, 1754, a young servant girl hard-boiled an egg, scooped out the yolk, and filled the hollow with salt before eating it, shell and all. Another girl, just as love-struck, carried in her coat pocket all day the peels of two lemons. At sunset she used them to polish her bed's four posts in hope that the object of her affection might appear in her dreams as altogether more willing than he showed himself in waking life.

As he sat correcting grammar exercises how could Herr Professor Unrat have known that one day he would meet his end at a dive named The Blue Angel, in the arms of a kohl-eyed blonde?

When virginal young ladies of northern England wished to dream of love they gathered on moonlit nights in groups of three to bake a cake from batter consisting of flour, salt and spring water. This confection they divided in three, and each third again in nine. They pushed these bits through the wedding ring of a woman who had been married exactly seven years. Then they slipped off their clothes, ate the cake, and cried out: "O', good St. Faith, be kind tonight, and bring to me my future husband view, and be my visions chaste and true!" Satisfied they had done all they could to win their swains, they went to sleep, all in the same bed.

Even kale, that vegetable today beloved of the diet-minded, had a place in the romantic's arsenal of charms. When the young women of Craven found themselves enamored they would perch upon a rock, holding a pot of kale soup, and sing:

Hot kale, or cold kale, I drink thee,

If ever I marry a man, or a man marry me,

I wish this night I may him see, to-morrow may him ken

In church, fair, or market above all other men.

They would then sip this broth nine times, walk backward to bed, and go to sleep.

Poor Cosmo von Wehrstahl: One night in a magic mirror he saw his love. But it was not to be. On a gloomy overpass he cut his wrists.

Darker charms existed for those who would punish inconstancy. An embittered suitor might wake at midnight to plunge pins into a bird's heart or wrap a lump of dragon's blood (a resin aromatic and crimson-colored) in paper for burning along with a hastily stitched effigy of his beloved. This immolation he hoped would cause her pain -- or at least a pang of regret.

"Over-indulgence in pleasure prevents the birth of love."

Such elaborate gestures could be said to belong more to the category of ritual than charm. Indeed, love charms were as often as not small, unassuming things -- necklaces and rings and small vials of unfamiliar powders. Many people favored love packets, which they could easily fashion and secret away. The Irish adorned theirs with suns and moons and magic squares. Into them they stuffed toenail pairings and underwear fragments. Amorous Turks similarly fashioned pouches to stuff with even stranger items: a man's molar and a particular bone in the left wing of a hoopoe (the bird sent by Solomon to the Queen of Sheba), among other things. Under the pillows of pretty women these parcels would go, put there in the hope of stoking passion for the bearer.

In Knut Hamsun's 1894 novel Pan, Lieutenant Thomas Glahn so loved Edvarda that he shot his dog.

Any increase in attraction as a consequence of such doo-dads likely owed more to common belief than occult forces. The objects of such charms and rituals certainly did complain of falling under their influence, blaming them for everything from disappointing marriages to illegitimate children. A dalliance had as its cause a strand of hair left on a pillow; an unexpected pregnancy, a lavender sachet. Such hexes people saw as matter-of-fact events. To disbelieve them they thought unwise.

"Love is the most dunder-headed of all the passions," said Edward Bulwer-Lytton, "it never will listen to reason."

Recipe for Scotch Kale Soup from The Thorough Good Cook (1896): "Put barley on in cold water, and when it boils off the scum; put in any piece of fresh beef and a little salt; let it boil three hours; have ready a colander full of kale, cut small, and boil it tender. Two or three leeks may be added with the greens if the flavour is approved of."

Reports of love magic now occasion only laughter. And the charms themselves seem much ado about nothing. Why bother prying a molar loose from an unsuspecting mans's jaw when innumerable lovers lie a mere mouse-click away? Instead of the crystallized bough, it's the liquid crystal display that serves as the vehicle for romantic metaphors. And that "dead blank" that struck fear in Stendhal's heart? It's just another failed page load in a web browser.