A fresh look at rotten food's influence on world events

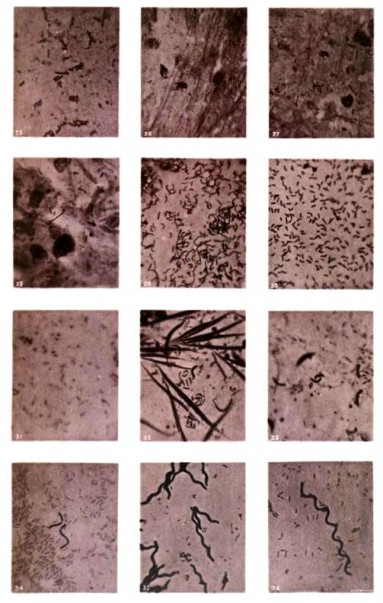

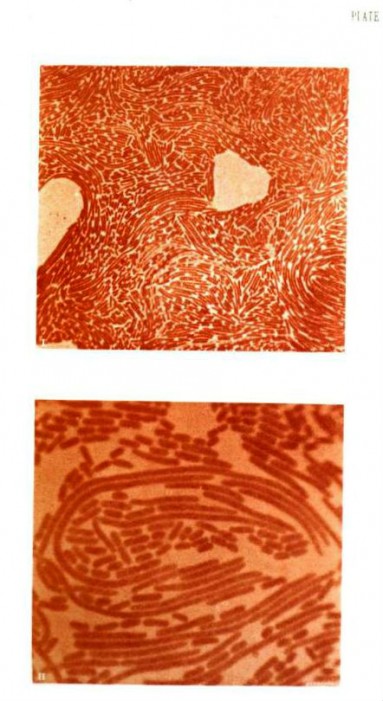

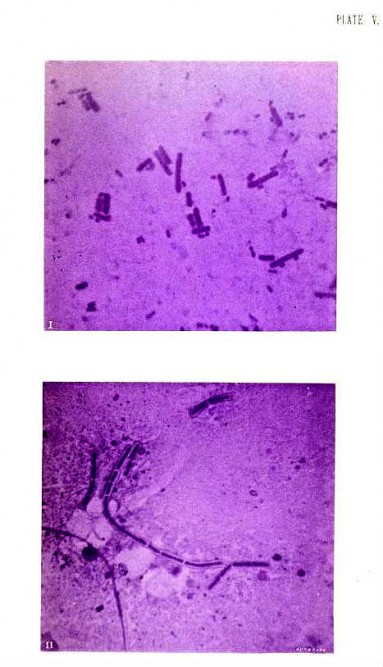

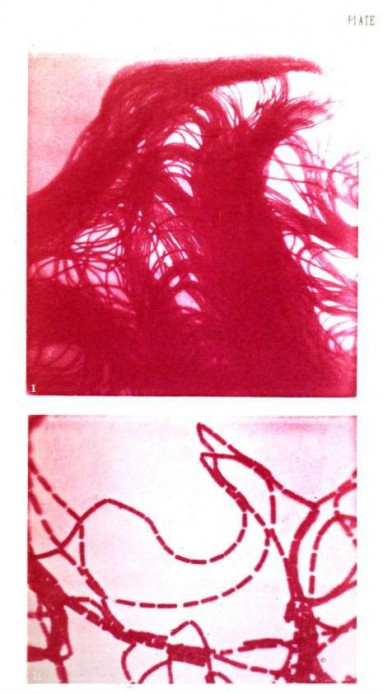

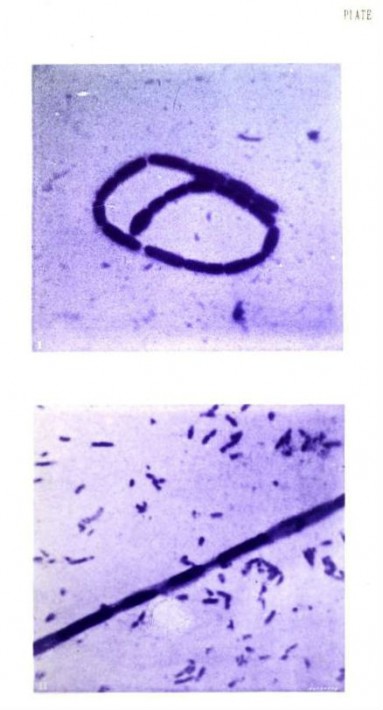

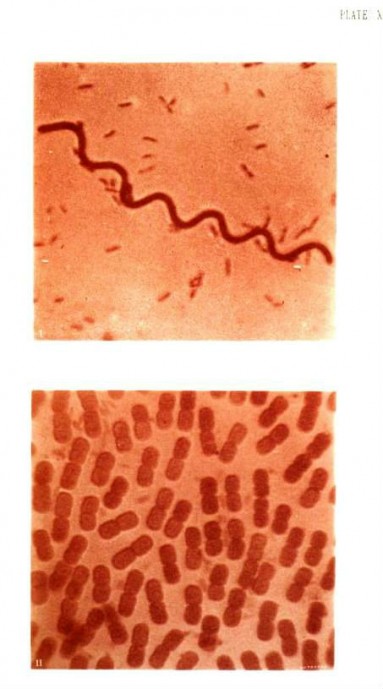

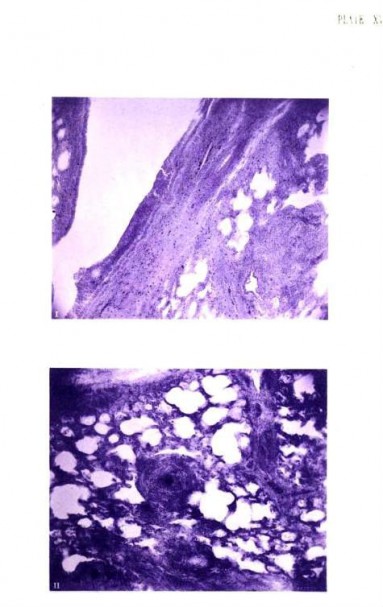

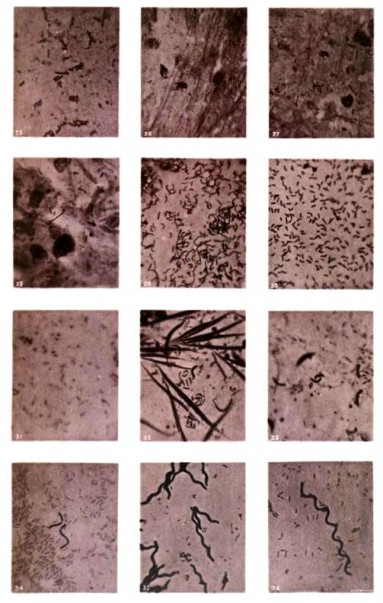

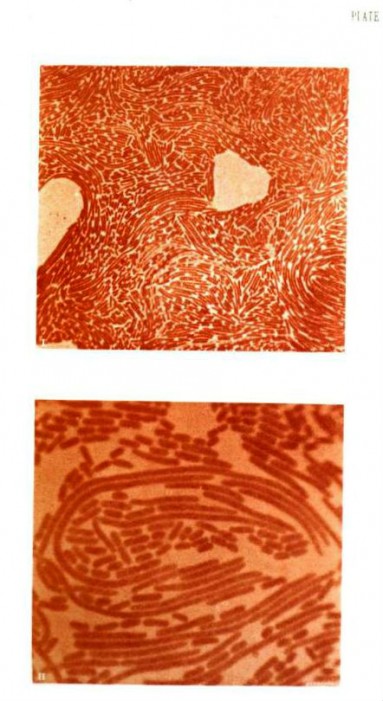

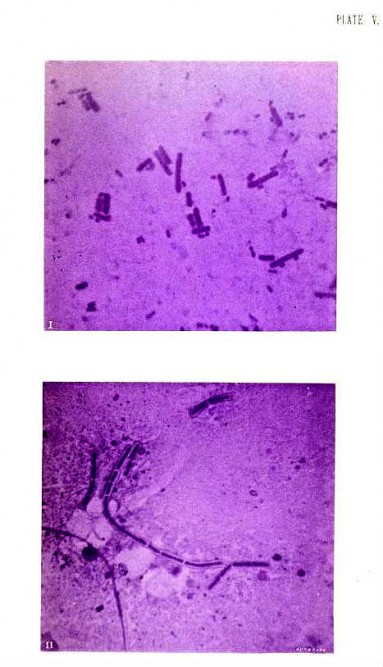

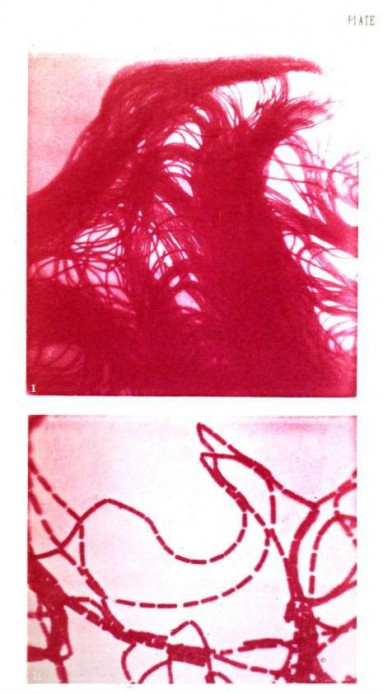

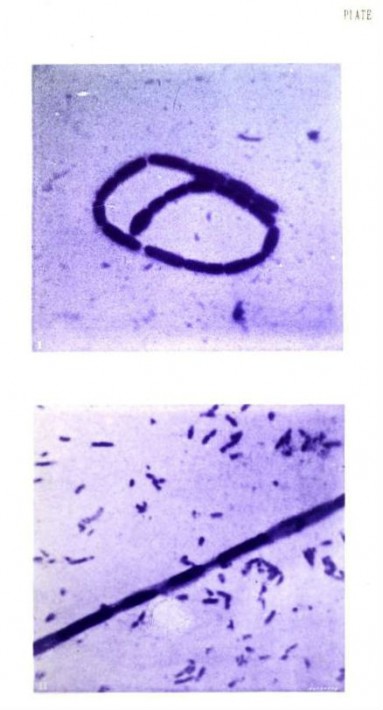

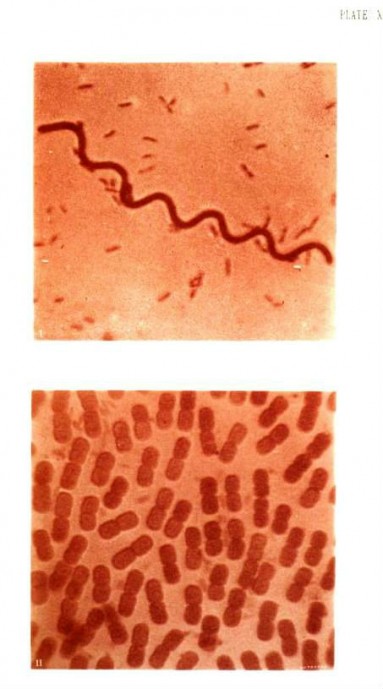

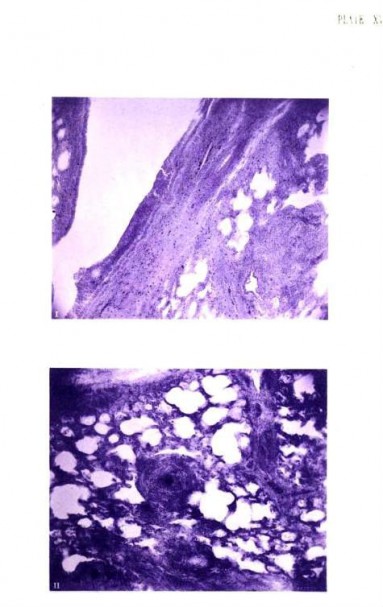

Images from Photography of Bacteria (1887)

Joyous but hellishly hot is no doubt how those in attendance would have described the Washington Monument’s groundbreaking ceremony, which took place July 4, 1850. Yet the heat didn't dampen the appetite of President Zachary Taylor

Among the 135 guests at Japanese Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa's January 8, 1992 state dinner was US President George H.W. Bush. During the meal, Bush grew ill and vomited on Miyazawa. So impressed were the Japanese with the event that they coined the term Bushu-suru, which means "to do the Bush thing."

, who presided over the event. "Old Rough and Ready," as he was affectionately known, snacked on cucumbers, "a generous quantity of cherries," and iced milk during the festivities, and he munched a few green apples while strolling afterward along the banks of the Potomac River. On returning home to the White House he capped his afternoon by drinking a few quarts of water.

Some few hours later Taylor complained he felt unwell. His stomach ached, and he experienced a strange, persistent pain in his chest. The next morning found him feeling worse. Nausea gripped him, as did cramps, diarrhea, and violent thirst. He took to his bed. His physician, suspecting onset of cholera, gave him mercury chloride and opium. His illness progressed nonetheless, weakening him to a point where the end seemed certain. "I am about to die," Taylor told his wife, whom he had summoned to his side. "I regret nothing, but I am sorry to leave my friends." Some five days after the ceremony and a mere 17 months into his term, die he did.

"To Beatrice, -- so radically had her earthly part been wrought upon by Rappaccini's skill, -- as poison had been life, so the powerful antidote was death; and thus the poor victim of man's ingenuity and of thwarted nature, and of the fatality that attends all such efforts of perverted wisdom, perished there, at the feet of her father and Giovanni." --Nathaniel Hawthorne, "Rappaccini's Daughter" (1844)

Taylor's passing inspired a good deal of speculation. Some claimed typhoid carried the chief executive off; others, arsenic. Investigations failed to clear up the matter, and consensus eventually settled on run of the mill food poisoning as cause. Cucumbers, cherries, unpasteurized milk, green apples -- anything Taylor had eaten that Independence Day could have been the culprit. Even the water he drank attracted suspicion, the capital’s sewage system then in a deplorable state. Whatever the fatal food, it lent truth to the observation made by Paracelsus some three centuries before: "Poison is in everything, and nothing is without poison."

If food didn't kill you, the pot in which it was cooked would. Cheaper grades of cooking utensils contained antimony (as did the rubber nipples on infant's bottles), a poison that works much like arsenic. Where there wasn't antimony, there was lead, which colored candies and decorating sugars and found its way into the bright foils that encased cheese and the stoppers that stopped soda pop bottles. It lined cans of tin, a material also believed to ruin health, and fortified the pipes that brought water into kitchens.

Poison was indeed in everything, and eating was a sort of gastronomic Russian roulette, as likely to bring illness or death as health. Time and chance determined which. Too many days in the larder and a pie went from tempting to toxic. Trafficking with the wrong dairy maid could result in tuberculosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, strep throat, or some other nasty bug. Someone tucking into a loaf of rye bread might begin to dance furiously or, if a pregnant woman, spontaneously abort her child. As if engaged in grim intrigue, Nature tainted oysters with typhoid, laced sausage with listeria, and corrupted pork and fish with worms. She soured cheese and mildewed ale. Few foods escaped her blighting touch.

Henry Purcell, one of Britain's greatest composers, was said to have died from consuming a cup of chocolate "at one of London's new chocolate houses."

Of course, human beings lent Nature a helping hand. Produce mongers, confectioners, vintners, brewers, bakers and butchers devised unwholesome methods of making their wares more appealing, even if it meant killing their customers. In the first century AD, Pliny complained about bread to whose dough bakers added white earth collected from a hill near Naples. It didn't help that he often had only adulterated Roman wine to wash down these clayey loaves. Especially noxious to the Roman physician were the Gaulish vintages altered "with smoke, and even ... with herbs and toxic drugs."

Joseph Addison on vintners: "These subtle philosophers are daily employed in the transmutation of liquors, and by the power of magical drugs and incantations raise under the streets of London the choicest products of the hills and valleys of France; they squeeze Bordeaux out of the sloe, and draw Champagne from an apple."

"What is food to one man is bitter poison to others." --Lucretius

A millennium and a half after Pliny made his complaint, London’s mayor, perhaps weary himself of bad wine, sent the King's finest vintners to inspect imported casks. In them they found more sulfur, wood bits, gravel, and weed clumps than claret. The Lord Mayor deemed the contents "unwholesome and of a nature similar to others formerly condemned and destroyed." Around the same time, the mayor of the English town of Guildford sought to stem the problem of adulterated alcohol with a team of elite "ale-tasters," who took an oath to "well and truly serve his Majesty and this town in the same office." Part of this duty involved performing an ingenious test. A lederhosen-clad man was commanded to sit on a wooden bench drenched with some new brew. After some hours he was asked to rise. Making it to his feet signaled pure beer. Remaining stuck in place indicated beer forced with sugar.

The punishments for culinary corner-cutting varied by country. The English contented themselves with public humiliation. Dishonest bakers and brewers were pilloried or paraded through town, usually with their tainted wares strung around their necks. Repeat offenders were jailed, incorrigibles exiled. But woe unto German cheats; Teutonic justice took a decidedly rougher tack. Offenders could be buried alive, crammed in baskets and dunked in muddy lakes, or burned at the stake. One Nuremberg merchant, Jobst Fendeker, suffered this third sanction in 1444, his executioners using as kindling the false saffron he attempted to foist on his fellow townsfolk.

The Greek poet and playwright Euripides lost his wife, two sons, and daughter to a dinner of death cap mushrooms. Pope Clement VII, Emperor Charles VI, and composer Johann Schobert also all died from eating poisonous mushrooms.

When not meting out punishment, government officials busied themselves issuing various assizes, decrees and acts against peddling unsound victuals. To them, it was simply a matter of self-preservation. Rotten food threatened state security. Contaminated grain proved the decisive factor in Athens’ defeat in the Peloponnesian War. Dishes of fly agaric mushrooms toppled (inadvertently or not) several Roman emperors. The English lost bad King John to putrid peaches and good King Henry I to turned lampreys. The latter's fate shows why it's wise to follow medical advice. A huge helping of the eel-like fish, his favorite delicacy, greeted Henry when he arrived home one November evening in 1135 from hunting in a forest near Rouen. His physician, however, had asked his king to swear off the stuff, fearing that it would upset the sovereign stomach. The king ignored this counsel and ate his dinner.

Henry I was a man of irrepressible appetites. He sired some 25 illegitimate children. Yet he was also high-minded in his way, and saw that most of them were provided for.

Chills and convulsions overtook him, and later death. So blighting an effect did lamprey flesh have that it nearly killed those who examined Henry’s remains. "[Upon] being opened," one eyewitness reported, "the Stink of his Body and Brains poison[ed] his Physicians."

Food poisoning sometimes toppled a king, sometimes an army. The American Civil War offers a dramatic instance of the second. Confederate army general Robert E. Lee lived little better than his soldiers

Lacking the tasty vittles of their Northern counterparts, Southern soldiers subsisted mostly on cornmeal, pork, and peanuts. They did, however, have access to ample amounts of tobacco.

. "If one wanted a poor dinner," it was said of him, "he had only to drop in on General Lee at that hour." Pained by Lee’s asceticism

"And soon after the Blessed One [Buddha] had eaten the meal provided by Cunda the metalworker, a dire sickness fell upon him, even dysentery, and he suffered sharp and deadly pains. But the Blessed One endured them mindfully, clearly comprehending and unperturbed." --Maha-parinibbana sutta, verse 21 (29 BC)

his cook tried to coax him to greater indulgence by preparing his favorite dishes. The cook knew Lee had a weakness for "old Virginia flapjacks ... thin as a wafer and big nearly as a cart wheel," and "served hot with fresh butter and maple molasses and folded and folded, layers thick." The Confederate army’s Pennsylvania campaign afforded the cook a unique opportunity to tempt his employer. "Well, I'se gwine to git something good for Marse Robert for once," he reportedly said, “if he never eats no mo'." To Southerners reputedly a land of milk and honey, the Keystone State countryside soon rendered up the ingredients for an uncommonly tasty version of the General's favorite meal.

Lee meanwhile had been strategizing his attack on Union major general George Meade's army. A whiff of the pancakes awaiting him got him to set aside maps and plans. He tucked into them with gusto, eating more at one meal than he had in a month. Agony followed ecstasy. The pancakes didn't sit well.

It is now known that Lee likely suffered from either shigellosis or salmonellosis and could not direct his army with his usual acumen.

Indeed, they left him bedridden. The armies clashed. "We must strike Meade a blow!" Lee cried from his tent. As it turned out, it was Meade who dealt the blow Lee meant for him. After three days of fighting, some of the bloodiest the war had seen, the Confederate army went down in defeat and the Union army on to further victories.

Recipe for "Stomach Bitters" from Dr. Chase's Recipes (1873): "European gentian, 1 1/2 ozs.; orange peel 2 1/2 ozs.; cinnamon seed 1/8 oz.; unground Peruvian bark, 1/2 oz.; gum kino, 1/4 oz.; bruise all these articles, and put them into the best alcohol, 1 pt.; let it stand a week, and pour off the clear tincture; then boil the dregs a few minutes in 1 qt. of water, strain, and press out all the strength; now dissolve loaf sugar, 1lb, in the hot liquid, adding 3 qts. cold water, and mix with the spirit tincture first poured off, or you can add these, and let it stand on the dregs if preferred."

"Men become accustomed to poison by degrees." --Victor Hugo

As time and science advanced, eating became less of a hazard. Stricter standards in food hygiene and processing made most foods safe to eat. Yet those culinary malefactors, the food adulterers, didn't exactly disappear with food-borne typhoid and diphtheria. Rather, they too made great advances. Bisphenol A, butylated hydroxyanisole, hydrogenated oils, propylene glycol, Red #40, Blue #1, and all the rest might not kill outright, deposing tyrants and vanquishing armies, but the damage they do shouldn't concern us any less. Poison is still in everything. Those who put it there just have better lawyers and lobbyists.