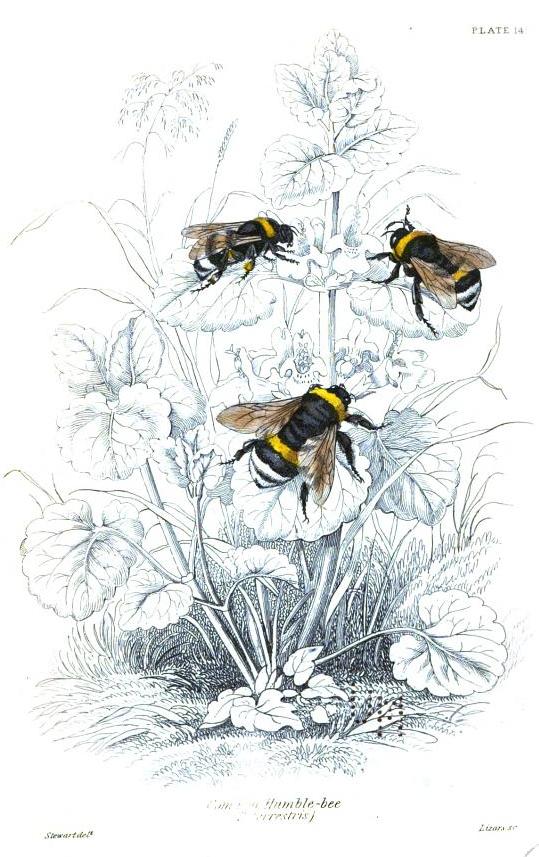

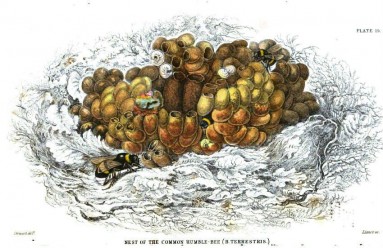

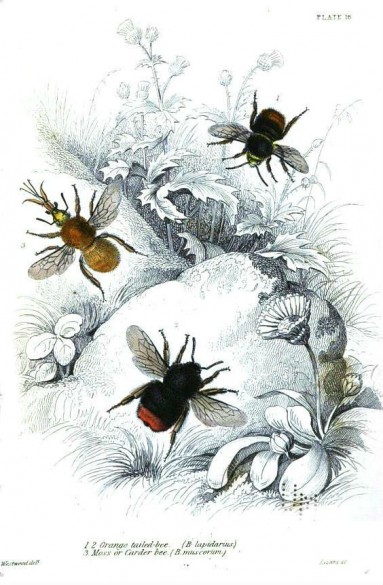

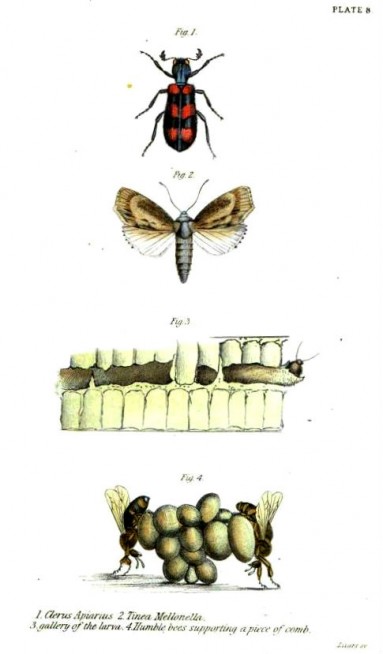

Illustrations from The Natural History of Bees (1840)

"Life is ever / Since man was born, / Licking honey / From a thorn." -- Louis Ginsberg

Of the various sorts of men blazing trails through the American frontier the honey hunter stood out as unique. Bold, elusive, secretive, he wandered much of the year, living off the land as he searched vast unclaimed forests for the pine stumps and oak hollows whose recesses harbored his liquid gold, and whose location, once discovered, he jealously guarded.

He held his honey in a hollow, tanned deer leg open at one end. When hungry he sucked from it a sweet supper.

"A taste of honey. / Tasting much sweeter than wine. / I dream of your first kiss and then, / I feel upon my lips again, / A taste of honey."

If he happened to have honeycomb he'd gobble it as if it were a custard tart. From time to time the richness of this meal would send him into a "honey founder": To the forest floor he'd fall, where he'd lay senseless for hours.

"Beekeepers may be divided into two groups, according to their intelligence, social and solitary. Social beekeepers associate, attend meetings, mix and mingle, visit and converse, read and study, observe and learn, and are benefited by the accumulative results of organized strength and activity. Solitary beekeepers potter, alone, groping in ignorance and we all know what sooner or later happens to them." -- From the Annual Report of the Illinois State Bee-Keepers Association (1922)

After Alexander the Great died, his subjects carried him thousands of miles home, where they buried him in a golden coffin filled with honey.

When not swooning from sugar shock, the honey hunter showed a talent for shrewd barter. His surplus store he'd swap for various necessities and the occasional luxury. "I have traded a bee [tree] for a Bible, for a load of pumpkins, for a colt, for a couple of shoats and even for store good, taking an order as good as the cash in payment," one honey hunter boasted. Operating without encumbrance of money gave such men a freedom unknown to their Old World counterparts. Unlike the domesticated apiarists of Europe -- the dutiful monk and obedient peasant plying their trade according to law and giving the king his due -- the American honey hunter labored for no master but himself. Independent and unbridled, he was perfectly suited to the new nation he called home.

Germans believed that bees must be told of their keeper's death, because leaving them uninformed would cause them either to leave the hive or die. In England, a hive moved slightly to the right by the keeper's son after his father's death signaled to the bees that in some small way the universe had changed.

"Mrs. Astley, wife of Mr. Astley, sen., used to exhibit a swarm of bees on her arms, shoulders, &c.; and Mr. Wildham possessed a secret by which he could at any time cause a hive of bees to swarm upon his head, shoulder, or body, in a most surprising manner." -- From The Pocket Magazine of Classic and Polite Literature (1830)

The honey hunter's freeborn ways weren't without consequence. His trade often caused him to ravage its source, unprotected wilderness. In 1837 a journalist voiced concern about "the damage done to forests by bee hunters." Good Christians, he observed, become half-crazed when searching for honey, hacking apart stumps, toppling any tree that betrayed signs of bees. A party of bee hunters could devastate an entire copse. In 1839 a group settling in Clarks County, Missouri uprooted in a few hours' time sixteen white oaks. Devastation of this degree was typical of the industry. Filling one barrel often required uprooting dozens of trees. And waste ran rampant. Whatever honey the hunters couldn't haul from the spot they left for ants and bears.

So few in the vast Hive remain; / The Hundredth part they can't maintain / Against th'Insults of numerous Foes; Whom yet they valiantly oppose; / Till some well-fenced Retreat is found; / And here they die, or stand their Ground, / No Hireling in their Armies known; / But bravely fighting for their own; / Their Courage and Integrity / At last were crown'd with Victory. / They triumph'd not without their Cost, / For many Thousand Bees were lost. / Hard'ned with Toils, and Exercise / They counted Ease it self a Vice; / Which so improv'd their Temperance, / That to avoid Extravagance, / They flew into a hollow tree, / Blest with content and Honesty. -- Bernard Mandeville, "Fable of the Bees" (1705)

Such destruction writer Washington Irving witnessed first-hand while traveling with an 1832 frontier expedition. In his remembrances of the trip, which he published in 1835 under the title, A Tour on the Prairies, Irving notes with bitterness the "wasteful prodigality of hunters

"For even honey in excess becomes gall."

." Yet a certain attraction tempered his censure. Irving found something undeniably compelling about the honey hunter's art -- so compelling, in fact, that he agreed to take part one summer's day in an Oklahoma bee-hunting party.

Irving and a half-dozen other men decamped for an open glade on the forest edge. Some carried rifles, others kettles and axes. The leader, a "tall lank fellow," wore a straw hat shaped like a beehive. Immediately upon entering the glade he set a piece of honeycomb on a low bush. It was an old trick, and each hunter had his favorite bait. Some used flour sprinkled on a plate, others relied on sugar.

Beehunters ignored all time schedules except their own, though their reputation did depend on how fast they could find a bee tree. The best did so in thirty minutes or less.

Honeycomb proved effective enough; soon bees came buzzing. They dipped into the tiny cells to take the bait before darting off to their hive. The honey hunters marked the bees' course, and then they too darted off. Swift as bucks they ran, their eyes fixed skyward, heeding not the roots and rocks over which they stumbled, attending only to the small cloud of insects above them. They followed the bees to their hive, which sat some sixty feet above the ground in the hollow of a dead oak. This the hunters attacked with axes. To repulse any stinging defense

"All that is accessible to man is the observation of the correspondence between the life of a bee and other phenomena of life. It is the same for the purposes of historical figures and peoples." -- Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace (1869)

they set fire to a bundle of hay. Minutes later the tree toppled, and the men fell upon the hive with spoons and hunting knives, scraping what they could of it from the rotted trunk. Like schoolboys they gorged on thick clumps of honeycomb and slurped honey both ancient and fresh -- the first dark as molasses, the second limpid as simple syrup. Undamaged combs they set aside and later placed in large kettles for transport back to camp.

Irving notes that it was "surprising in what countless swarms the bees have overspread the Far West within but a moderate number of years. The Indians [the Osage and Pawnee] consider them the harbinger of the white man, as the buffalo is of the red man; and say that, in proportion as the bee advances, the Indian and the buffalo retire."

This scene Irving witnessed in wonder. His sympathies rested less with the men than with the bees, who toiled even as their hive fell under siege. "They continued to ply their usual occupations," he remarked, "some arriving full freighted into port, others sallying forth on new expeditions." Even the loud crack that announced the tree's impending fall "failed to divert their attention from the intense pursuit of gain."

"Notice that 'I' is at the center of w-i-n." -- Bertie Charles Forbes

In their conduct they reminded Irving of "so many merchantman in a money-making metropolis, little suspicious of impending bankrupcy and downfall." When that downfall occurred, and the tree burst from end to end, "displaying all the hoarded treasures of the commonwealth," the honey hunters were not the only ones watching in anticipation. "I beheld numbers from rival hives, arriving on eager wing," Irving continues, "to enrich themselves with the ruins of their neighbors." These interlopers feasted on the spoils while the "poor proprietors" of the ruined hive crept back and forth in vacant desolation. It was a scene, Irving concluded, that Shakespeare's "melancholy Jacques" might have moralized to excellent effect.

Recipe for Honey Mousse from Honey and Its Uses in the Home (1915): "4 eggs, 1 cup hot, delicately flavored honey, 1 pint cream. Beat the eggs slightly and slowly pour over them the hot honey. Cook until the mixture thickens. When it is cool, add the cream whipped. Put the mixture into a mold, pack in salt and ice [or refrigerate], and let it stand three or four hours."

With the end of the 19th century came the end of the wild honey surfeit. Like their quarry, the hunters found themselves deprived of land they once thought theirs by natural right. "Everyone wants to speculate and monopolize things nowadays," they complained. Wild forests and open ranges farmers and ranchers cultivated and enclosed. Though honey hunting continued in half-wild, poverty-stricken backwoods, laws curtailed the practice. In meadows "No Trespassing" notices shot up like dandelions. The sedentary tiller and husbandman displaced the roving forager, and beekeeping became a sideline of science-minded merchants. Ceding to a manifest destiny of property from sea to shining sea, the American frontier disappeared, sparing the bees and the trees that housed them from the bitter consequences of the itinerant honey hunters' sweet obsession.