Illustrations from Mara Louise Pratt-Chadwick's Three Pigs... (1905)

Like the saint, the philosopher and the poet, the pig enjoys only posthumous appreciation. While alive, he finds himself scorned and derided. The public considers him vile, a creature of appetites and odors -- and little besides. "In aspect and general form he is not merely uninviting, but absolutely repulsive," writes H.D. Richardson in Pigs; Their Origin and Varieties (1847)

"I am fond of pigs. Dogs look up to us. Cats look down on us. Pigs treat us as equals." -- Winston Churchill

. "[E]very moment of his life-time is seemingly devoted to the attainment of sensual or disgusting objects, which constitute his enjoyments." Such apparent abandon to base pleasures explains his pariah status. Better tasted than seen or heard was the attitude most folks had toward him.

In The Intelligence of Animals: With Illustrative Anecdotes (1869), author Ernest Menault reports that his fellow writer Bernard Gilpin upheld the notion that "with kind treatment, a pig may become an 'orderly, docile animal," though Gilpin did also admit that the pig "may a have a degree of positiveness in his temper." This latter observation leads Mendault to ask, "[M]ay not that much be said of many men -- ay, and of women too?"

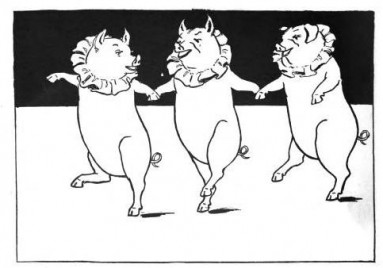

A few men saw past the pig's more off-putting qualities to find delight in the creature's surprising cleverness. When ill, Louis XI loved to watch a pair of dancing pigs who, dressed like gentlemen and ladies, pirouetted to the rhythms of a drum and tabor. Animal trainer Charles Barry taught a troupe of pigs to climb ladders, form pyramids and walk on their hind legs. For their efforts they received a bucket of slops. Yet even these animal acrobats didn't manage to dodge the swine's usual fate. Barry's players stalked the footlights for a single season, after which they "retired" to the local butcher shop. It then fell to their replacements to ham it up for the patrons in the cheap seats.

"'The meat must be well bled, and to do that he must die slow. We shall lose a shilling a score if the meat is red and bloody! Just touch the vein, that's all.... Every good butcher keeps un bleeding long. He ought to be eight to ten minutes dying, at least.'" -- from Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure (1895)

Since almost all pigs ended up as so many cutlets, going out with a bang was the most they could hope for. You could find no celebration of porcine flesh more spirited than the Cajun

boucherie, a day-long cookout common in the era before refrigeration. Hundreds of people attended these events, and each eagerly stood by to see a pig dispatched and cooked.

Recipe for boudin rouge from The Picayune Creole Cook Book (1922): "Boudins are blood sausages and are much affected by Creoles. Take 1 Pound of Hog or Beef Blood (1 pint). 1/2 Pound of Hog Fat. 2 Onions. Salt, Pepper and Cayenne to Season Highly. 1/2 Clove of Garlic. Mince the onion fine and fry them slightly in a small piece of the hog fat. Add the minced garlic. Hash and mince the remaining fat very fine, and mix it thoroughly with the beef blood. Mix the onions, and then season highly, adding of allspice, mace, clove and nutmeg a half teaspoonful each, finely ground, and a half teaspoonful each of fine herbs. When all is mixed, fill the prepared casings, or entrails, pressing them full, being careful to tie the sausage casing at the further end before attempting to fill. Then tie the other end, making the sausage into strings about two feet long. Wash them thoroughly on the outside again, and then tie them in spaces of three inches or less in length. Place them to cook in a pot of tepid water, never letting them boil, as that would curdle the blood. Let them remain on a slow fire till you can prick the sausage with a needle and no blood with exude. Then take them out, let them dry and cool. Boudins are always fried in boiling lard. Some broil them, however."

And what delicacies they made of the humble swine! For one kind of sausage, women mixed minced pork and liver with rice and seasonings. This they stuffed into cleaned intestines and boiled in a vat until white and firm. A darker, earthier sausage (

boudin rouge) they made with the pig's blood. Every part these cooks transformed into something tasty. His head, feet and shoulders they boiled in a vat, mixed with herbs and spices, and stored in a cool place to gel into a cheese-like block. His stomach they stuffed with veal and rice and then for several hours steamed until firm. His skin they fried in a vat of hot fat and dusted with cayenne. Stew also they made of him, one which featured as the main ingredient two-inch chunks of spine browned with vegetables and doused in a reddish-brown roux. This stew's appearance traditionally heralded the end of the festivities.

Come dusk the festival participants stumbled home drunk on beer and dyspeptic from huge helpings of sausage, cracklings and stew. Despite the wanton merry-making, nothing of the pig went to waste. As if mindful of Grimod de la Reynière's maxim, "Dans le couchon, tout est bon" ("Everything in a pig is good"), the revelers consumed snoot, tail and everything in between. That the pig himself could not partake of the festivities remains one of life's more unfortunate ironies.