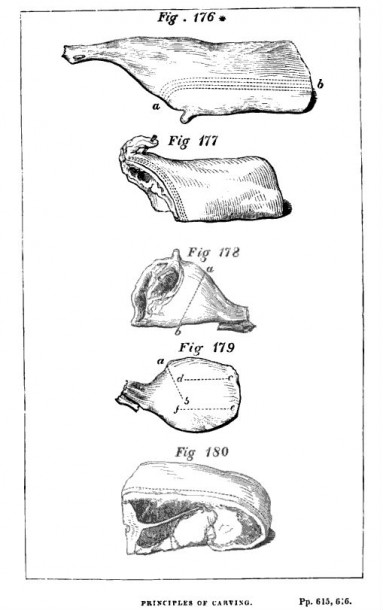

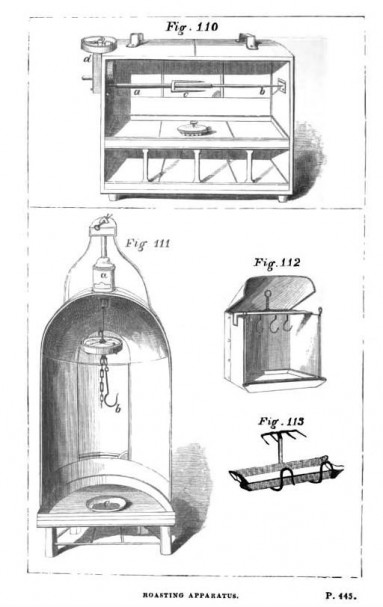

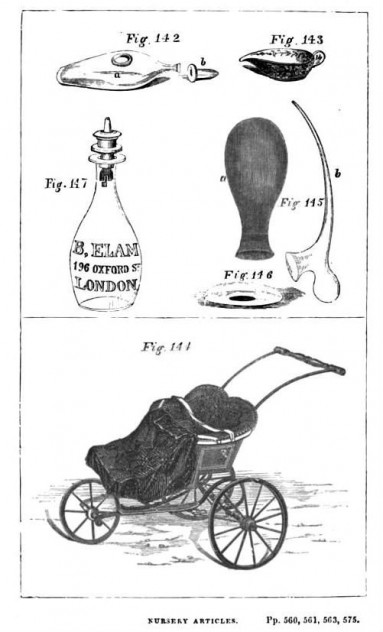

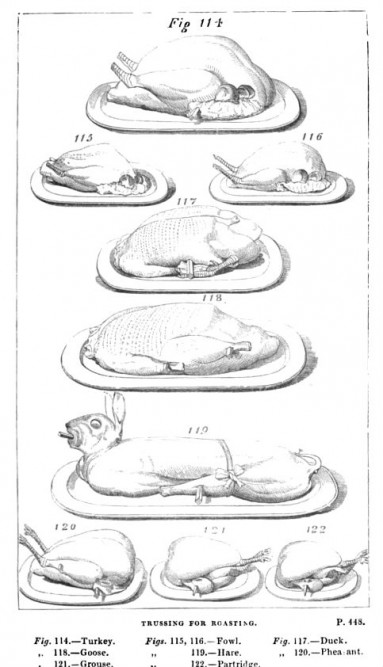

The discreet charms of the bourgeoisie owe something to the attractions of life as conjured by cookbook authors

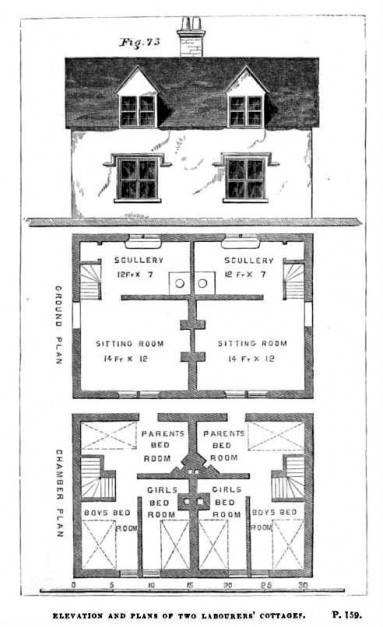

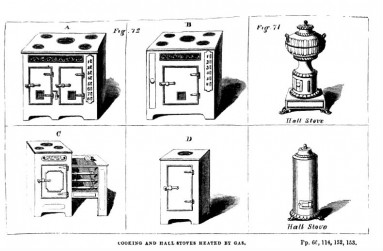

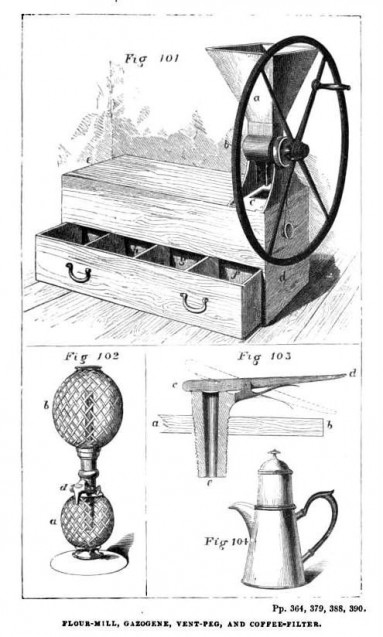

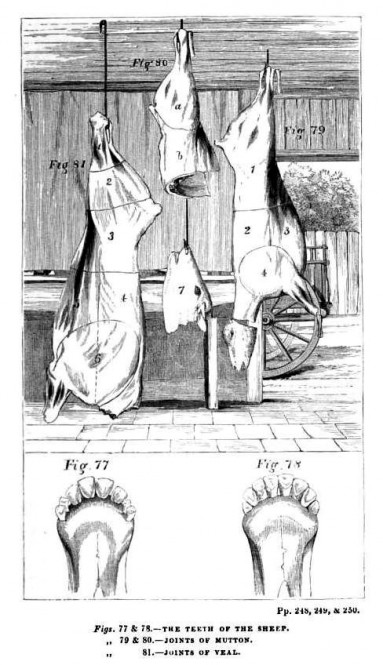

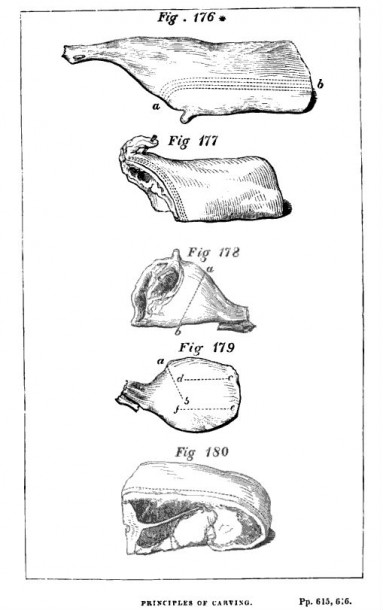

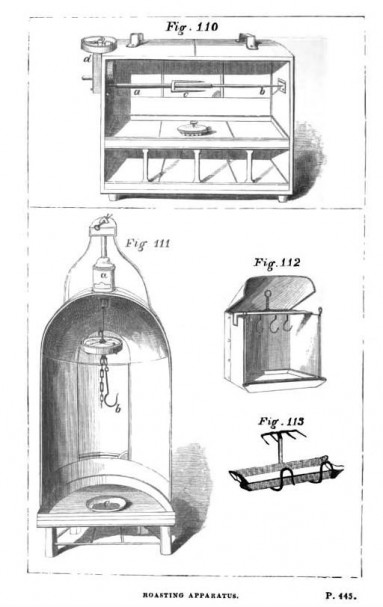

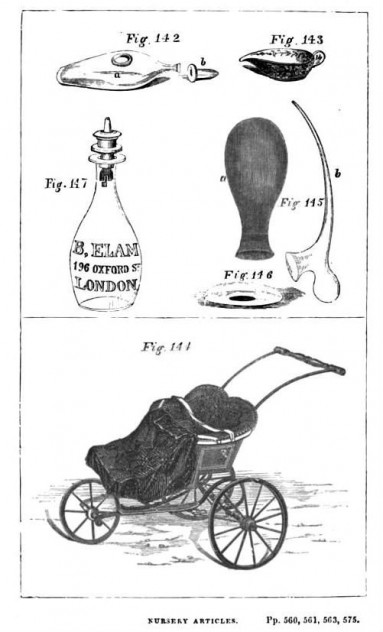

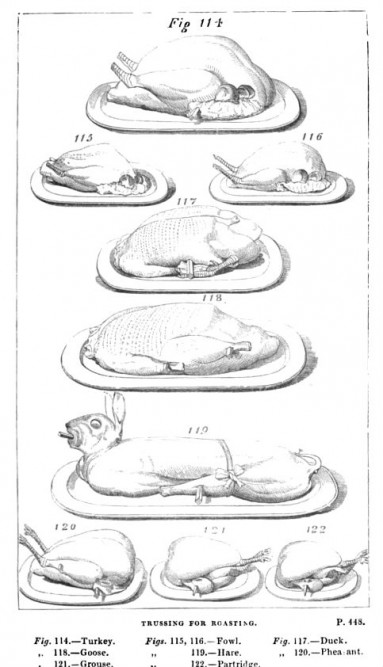

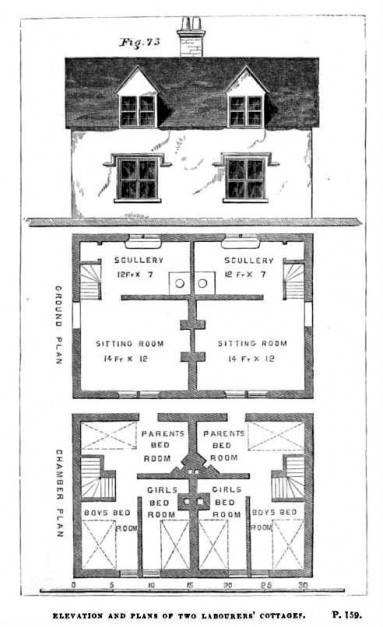

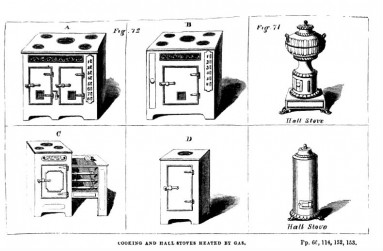

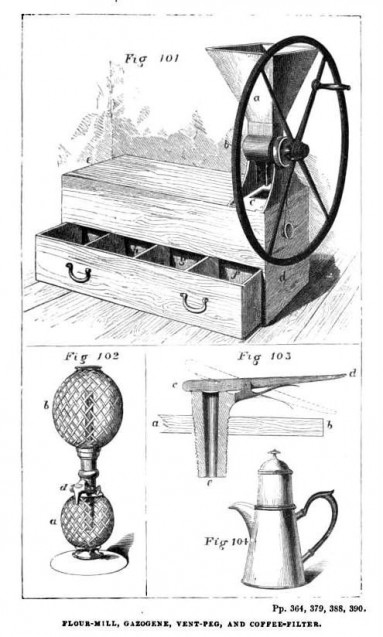

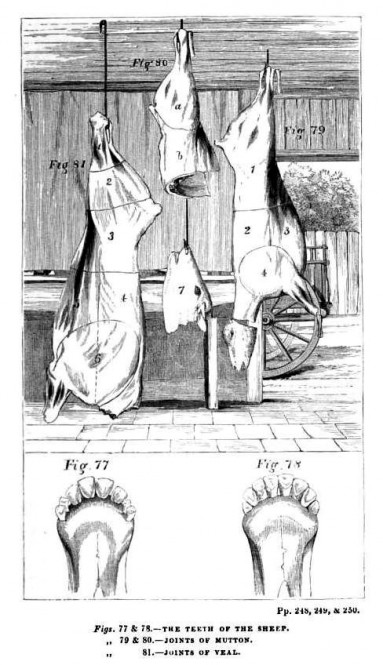

Images from a A Manual of Domestic Economy: Suited to Families Spending from £100 to £1000 a Year (1856)

Books are for people who wish they were somewhere else. --Mark Twain

Each year I vow to buy fewer books, especially cookbooks. And yet each week I find myself bringing home two or three new ones. I find them -- or rather they find me -- in the usual places: yard sales, flea markets, used bookstores, Goodwill. Earlier this summer I had to stop myself from saving some volumes of Time Life's

Foods of the World series, which I already own, from a “free pile” outside the Peaks Island branch of the Portland public library. They were eventually pulped, no doubt.

What is it about cookbooks that makes them so irresistible?

The answer may lie in the first printed cookbook, which was published 20 years after Gutenberg’s Bible. Bartolomeo Platina’s On Honorable Pleasure and Health (De honesta voluptate et valetudine) addressed “the citizen who wishes good health and a clean life rather than debauchery.” A surprising number of people wanted to read about the pleasures of moderation: When the book was printed 1474, it became an instant bestseller. A first edition appeared in Rome. A second Venetian edition followed soon after, and dozens of additional editions in Germany, Switzerland, and France soon after that.

Why was On Honorable Pleasure so popular? Perhaps because it was among the first printed cookbooks to promote personal health and happiness -- a compelling idea for a society in many ways still medieval in character. Platina showed his fellow Europeans that preparing a tasty ragout could be personally fulfilling, and that dining well was essential to living well.

"It would seem that nearly all the French cooks of prominence keep a diary in which they enter their various discoveries and write at length about the invention of certain dishes. Charles Reade, in one of his novels, gave a most amusing picture of a French cook who always put on a certain velvet jacket and smoking cap, and assumed a poetical position by a window which overlooked a broad expanse of woodland country. He would study the light and shade on the trees and repeat verses to himself, while one of the housemaids thumbed a guitar gently in an adjoining room. Thus his mind was composed and turned on poetical matters, and when he perceived that he was attuned to a high standard he would begin the composition of the menu for that night's dinner. The most intense silence was maintained throughout the regions of the kitchen while this important work was going on. When the menu had finally been completed the cook would rise with a deep sigh, throw off his cap, brush back his hair, and consume a cigarette while he talked affably to the housemaids with the air of a great man who had succeeded in completing a great work." --From "Cooks and Cook-Books," Good Housekeeping, Volume 11 (1890)

The book’s unique take on cooking reflected the urbane nature of its author. Born Bartolomeo Sacchi in 1421, Platina hailed from the northern Italian village of Piadena. Of a poor and obscure family, a teen Platina fought as a mercenary soldier in the endless wars among the region’s great families. He later moved to Mantua to study under Ognibene da Lonigo, who would come to preside over the great humanist school at Casa Giocosa near Gonzaga palace. A charming man, Platina soon became a tutor to the children of Ludovico Gonzaga himself. The job evidently agreed with him, for it was in Mantua that he began his first known literary works. But Platina’s natural curiosity and zest for life was such that he could not stay in one place for long. In 1457 he went to Florence to study under the Greek scholar Argyropulos, and a few years later he made his way to Rome.

There his intellectual life would continue to develop. In 1463 Platina summered near Lake Albano, where he met Martino, the celebrated chef of Cardinal Ludovico Trevisan. For Platina the meeting proved fortuitous. Martino gave him a manuscript of his cookbook, the Book on Culinary Art (Libro de arte coquinaria). This would become the inspiration for Platina’s own domestic manual, On Honorable Pleasure and Health, which was completed in the summer of 1465.

Part cookbook, part life manual, On Honorable Pleasure and Health addresses itself less to an economic than to an intellectual elite consisting of men with quick wits, humanist impulses, and a keen interest in reviving classical learning. They took seriously the maxim of the great humanist figure Erasmus, who wrote, “Your library is your paradise.” Indeed, they believed that in the pages of their libraries’ volumes could be read the plan for a veritable heaven on earth; study of Greek and Latin texts could spark a new era of universal peace and accord. Reality fell short of expectations. Reading Plato and Aristotle could not stop war altogether, but it did spark interest in Greek and Roman technical writing, which in turn influenced the development of European science. Perhaps the best-known personality of this period, Leonardo da Vinci, though himself not a humanist, typified the Renaissance’s humanistic spirit in his polymath’s verve, studying everything from human anatomy to weather, designing mechanical devices, and creating masterworks of art.

Platina brought this humanistic spirit to the compilation of On Honorable Pleasure and Health. His recipes borrow heavily from classical Greek and Roman texts, as well as Arabic dietetic tradition, which urged using food to cure sickness. “As long as you can heal with food, do not heal with medication,” said Persian physician and philosopher Muhammad ibn Zakariy? R?z?, who, active around 860-923 CE, was known as the “Arabic Galen,” after the influential Greek physician.

Humoral theory particularly loomed large in medieval and Renaissance medical thinking, and it plays an important role in On Honorable Pleasure. Health as well as personality came under the influence of humors. Imbalanced humors were believed to be the source of all illness. Certain foods balanced humors to restore wellness. Yet cooking was itself something of a balancing act, because food also had its humorous qualities. As a consequence of the blood in it, which brought it into association with water, beef was roasted in order to dry it. For the same reason, fish was fried and served with a cinnamon–vinegar sauce. Humors determined the seasonability of foods as well as their seasoning. “Moist” cucumbers and marrow (a type of gourd) were prepared during hot, dry summers; “warm” radishes during frigid winters. Depending on a person’s disposition, however, no season for eating attended some foods. Mushrooms made melancholy souls more so, as did eggplant and other moist, earthy vegetables. “Hot” vegetables, turnips inflamed passion; already choleric types ate them at their peril. (For phlegmatic types, meanwhile, they may be just what the doctor ordered.)

"All education begins at home. The home is the most powerful and really the most effective institution on earth for training the rising generation. Home influence is the truest character moulder; and if continued from infancy through early childhood to manhood, it will shape the moral and intellectual man or woman in spite of all outside directive power." --Walter Raleigh Houghton, Rules of Etiquette & Home Culture (1893)

All these rules and dictates Platina had to take into account. Indeed, the pleasure alluded to in the book’s title refers to pleasure gotten not from gluttony but from strict adherence to a humor-friendly diet. A pleasure, in other words, quite distinct from the things we imagine today to be pleasurable. In Platina’s time, pleasure essentially meant good health, and it “derives from continence in food and those things which human nature seeks,” he writes in his introduction. Whatever savor is to be found in chickpeas takes a back seat to their potent ability to “take away obstructions from the spleen and liver, break stones, purge the kidneys and bladder, make the voice clearer, arouse passion, and drive worms from the stomach.”

"There are three ingredients in the good life: learning, earning and yearning." --Christopher Morley

Yet Platina gives every indication that he believes flavor and health can coexist, provided they do so in a, yes, balanced way. That a pie filled with sweetened pork fat tickles the taste buds takes nothing away from the fact that it also warms the liver. His recipes therefore balance simplicity with sophistication. And they are remarkably cosmopolitan, showing Spanish, Arab, French, and Italian influences. Seasonably available, locally sourced ingredients -- rice from Lombardy, sausage from Bologna, seafood from Venice -- share the spotlight with more exotic fare.

"For while the aesthetic element must be subordinate to the requirements of physical existence, and, as a matter of expense, should be held of inferior consequence to means of higher moral growth; it yet holds a place of great significance among the influences which make home happy and attractive, which give it a constant and wholesome power to the young, and contributes much to the education of the entire household in refinement, intellectual development, and moral sensibility." --Catherine Esther Beecher, The American Woman's Home (1869)

Platina also thought that how one ate was just as important as what one ate. His is the first cookbook to elaborate principles of a recognizably modern gastronomy, emphasizing everything from the importance of clean tableware and spotless linen to installing attractive seasonal decorations. A table set “in cool and open places” and a floor strewn with “fragrant boughs of trees, of vine, and of willow” enhance summertime joys. Arranging flowers “in the dining room and on the table” is urged as a rite of spring. The dining room in winter “should be redolent with perfumes,” and in autumn “ripe grapes, pears and apples” should hang from its ceiling.

"One may have a blazing hearth in one's soul and yet no one ever comes to sit by it. Passersby see only a wisp of smoke from the chimney and continue on the way." --Vincent van Gogh

Such domestic advice might seem fusty to us, but for a growing middle class whose immediate parents and grandparents likely toiled in medieval drudgery, Platina’s book revealed to them a new world of possibility. This world was secure enough from war, famine, and disease that people of less than noble lineage could think about such seemingly unimportant things as entertaining. It invited them to dream of domestic comforts and personal health and happiness -- ideas as strange to them as, say, a work-free world would be for us. Yet as economic conditions favored the pursuit of these ideals (and as any domestic maven knows they can never be completely realized -- a fact which adds to their allure), Platina’s beguiling domestic phantasmagoria took root in the bourgeois mind. And it continues to inform our domestic imagination as made evident in everything from

Delia Smith's Cookery Course to Martha Stewart's

Entertaining.

Recipe for Fennel Buns from Platina's On Honorable Pleasure and Health (1465): "The ... baker should mix as much flour with warm water as is enough to make a bun and then put into the mixture fennel seeds and chopped bits of lard, or butter, and mix again as long as necessary to bring it all into a single mass. Then he should press it into a round shape with his hands and put it in the oven with the bread, or he may bake it on a hearth under a lid covered with ashes and coals."

And so in

On Honorable Pleasure and Health we find an early instance of what would make cookbooks so beloved: glimpses of our lives as we’d like them to be. “In the history of Western publishing,” observed cookbook historian Waldo Lincoln, “cookbooks have produced more bestsellers than any other genre.” It’s exactly that fact which gives me peace of mind. Those Time Life books may have been pulped, but tucked away in basements and piled on bookshelves are millions more, each promising a world of comfort and ease through cosmopolitan cookery. It's a fantasy that under conditions of capitalism tend to be exclusive if not zero-sum, to be sure. But if we could make that ideal more inclusive, cookbooks just might become the revolutionary texts they had once promised to be.