Rights are not rights if they are withdrawn in response to their use, in anticipation of their use, or to prevent them from being used.

This is such a simple point, but it sort of needs to be shouted from the rooftops: to change the basic and fundamental framework of the law in response to the crisis of the moment – or what is deemed to be a crisis – is to clarify that the law is a dead letter, like a fire insurance policy that is not valid in cases of fire.

I’m talking, of course, about the passage yesterday of Québec's Bill 78 – which lasts for one year or until dissent is crushed, whichever comes first – because the second part of this sentence is (or should be) implied by the first:

The Québec legislature passed a special law to stop this spring’s protests late Friday afternoon as a crowd of legal experts lined up to say the legislation goes too far and contravenes fundamental rights.

This, for example, is just crazy silliness:

Education Minister Michelle Courchesne, less than a week in her new position, raised more than a few eyebrows by mentioning that tweets from the social network website Twitter could also be considered as encouragement to protest. When asked to clarify, she said she would leave it up the police's discretion to deem what was within the limits of the law. It remains unknown whether "re-tweeting'' a potentially illegal message could also land others in hot water.

Which leads me to wonder: is this facebook message (describing the law and asking for legal and financial assistance) now a criminal act? “Pending police discretion” are not comforting words:

Among other draconian elements brought forward by this law, any gathering of 50 or more people must submit their plans to the police eight hours ahead of time and must agree to any changes to the gathering's trajectory, starttime, etc. Any failure to comply with this stifling of freedom of assembly and association will be met with a fine of up to $5,000 for every participant, $35,000 for someone representing a 'leadership' position, or $125,000 if a union - labour or student - is deemed to be in charge. The participation of any university staff (either support staff or professors) in any student demonstration (even one that follows the police's trajectory and instructions) is equally punishable by these fines. Promoting the violation of any of these prohibitions is considered, legally, equivalent to having violated them and is equally punishable by these crippling fines.

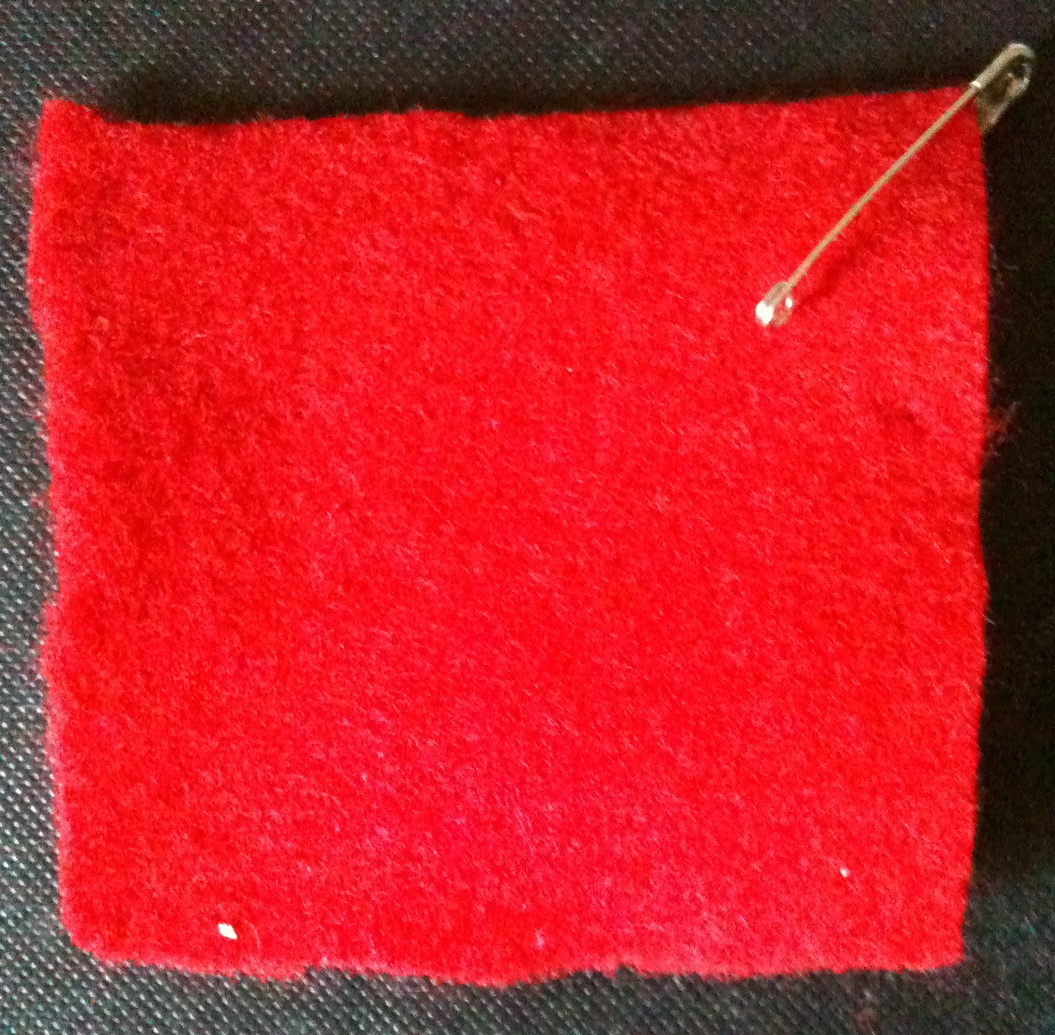

Reportedly, the minister of Education declined to explicitly deny that wearing a red square in public would now subject the wearer to criminal penalties. She was asked whether it was now illegal to wear a red square, and she did not say no.

But these are details, and we should keep our eyes on underlying principles. Because it’s not like any government anywhere has ever really legalized dissent, or categorically allowed any or all forms of assembly and expression; at least some kinds of normative limitation on civil behavior in public is and has always been fundamental to state behavior, since forever, for good or for ill. This is true in states (like the U.S.) that are, in theory (or from an American pov), more absolutist about free speech than states like Canada or Great Britain.

But. What this law explicitly demonstrates is that “normative” is a moving standard, that it will be pegged to political outcomes and the desire of the political class, and not by underlying principles or constitutional necessity. If you are tailoring the legal framework (for all) by reference to the government’s imperative to stop a specific protest, in other words, you are not only saying that ending a protest is the government’s responsibility, but that once the protest is over, the right to protest will return. Think about that for a moment. And while you’re thinking about it, read this:

Bill 78 quickly earned praise Friday from some pro-business institutions. Michel Leblanc, president and chief executive of the Board of Trade of Metropolitan Montreal, welcomed it as a way to protect downtown businesses. Many have complained that they are suffering because of the frequent demonstrations. Leblanc noted that fewer people have been heading to stores and restaurants in the business district since the protests started. "The objective was to pause the troubles," he said of the bill in an interview. "It was important to find a way to calm the city."

The Globe and Mail – Canada’s national newspaper – is in favor of the law, and the reasoning of this editorial demonstrates the kind of logic (and subterfuge) driving it quite nicely:

Canada has no “freedom of assembly” in its Charter of Rights and Freedoms. It has a “freedom of peaceful assembly.” The distinction means everything in the context of the student unrest in Québec. An element of intimidation and physical threat has been part of the demonstrations over planned tuition increases for the past 14 weeks. There have been serious outbreaks of vandalism and violence, and student leaders have made no attempts to do anything about them. The Québec government of Jean Charest has a duty to bring the province under control, and the law it has proposed would, with some tweaking, be a fair and constitutionally permissible means of doing so.

We start with lip service to the principles in Canada’s Charter, which is meant to assert that the bill is essentially in keeping with enshrined principles. But the law goes WAY beyond outlawing “vandalism and violence,” which are already illegal; the law not only does things like require 8 hour notice be given by protesters to police of the protests route, it does so, specifically and explicitly, because that kind of legal sanction is the tool the government has chosen to use in its war on the students. And if that doesn’t work, it will adopt different ones: the Québec government “has a duty to bring the province under control,” which is to say, until the standard for “control” is met, the actual letter and spirit of the law is irrelevent. Even this editorial – which begins with the assertion of the law’s essential adherence to Charter principles – acknowledges that some “tweaking” will be required to make the law “fair and constitutionally permissible.” In other words, even this argument in favor of the measure acknowledges that controlling the students is more important than petty details like fairness and constitutionality, and that we'll get back to you on that whole "legality" thing. This is not legality; this is the argument that il faut défendre la société contre les étudiants.

(For more, see Student Activism)