(A review of Michael Onsando's poetry chapbook, Something Quite Unlike Myself, by Kenyan poet and friend of the blog Stephen Derwent Partington, first published in Kenya's "Saturday Standard" newspaper, reprinted with permission)

When cowardly local publishers abdicate their cultural obligations and fail to print any decent local verse whatsoever, brave poets go abroad or go it alone. Increasingly, talented new Kenyan poets are finding that they must turn to self-publishing. Even our younger, funkier presses seem to privilege fiction over poetry; some newspaper and magazine editors seem pathetically confused by the genre, and avoid it altogether. Many fine Kenyan poets, most of them young, have necessarily self-published.

The most recent entry into our Kenyan pantheon of ‘Talented Poets who give a Damn where Publishers Don’t’, is award-winning social blogger Michael Onsando, with his excellent new chapbook, Something Quite Unlike Myself. A chapbook is a pamphlet of just a few pages, often self-produced and invariably less expensive than a full-length collection of the standard 60-70 pages.

Onsando’s chapbook is easy to slip into the brown envelope you’re carrying, or the iPad case you’re skipping around with, or the huge Dan Brown novel you’ve spent thousands of shillings on at the expense of more interesting Kenyan writers. Like the publishers, you people are borderline cultural traitors, hehe. People, you can redeem yourself a little by buying Something Quite Unlike Myself, a series of easy-to-digest poems which, nevertheless, are packed with meaning.

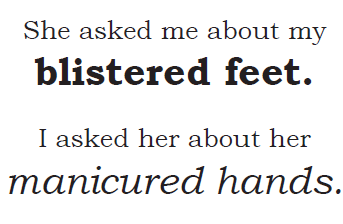

That’s the joy of good poetry: it condenses meaning into a tiny linguistic espresso. This makes it tougher and more resilient than fictional prose, more able to withstand all manner of interpretations. Look, for instance, at Onsando’s untitled four-liner, reproduced alongside this article. The words alone would do something, even if they were all presented as a single sentence. But with that punctuation and the different fonts, something else happens; something greater.

It is an enigmatic little poem, one posing more questions than answers. This is a consequence of the poem’s conciseness, its brevity. We ask ourselves: Who is the speaker, and who is the woman in the poem? Is Onsando the speaker, and what has he been doing to get blistered feet? Are they blistered now, as she views them, or is the woman asking him, during a meeting after the event, about his feet that were blistered some time ago? Are they lovers? (If so, the lines would be recited with love, concern and interest, as if the questioners are sympathetic: ‘Oh, I’m sorry about your feet’; ‘Oh, your hands look beautiful’). But Onsando leaves the context unsaid, and so it’s possible that the two characters in the poem actively hate each other and the whole verse is instead a two-way diss, the opposite of loving; we could then paraphrase the first couplet as ‘Goodness, your feet look terrible’ and the second as ‘Well, your hands look stupid!’ Or perhaps these are sly, backhanded compliments from two snooty wits to each other. We don’t simply don’t know. We have to guess. We have to participate! Yes, reading can get your brain off its ass(!?)

Varying fonts is a strategy used by Onsando in many of his poems. Here, it draws attention to the two qualified nouns (‘blistered feet’ and ‘manicured hands’) and adds a visual dimension that works to blur the division between visual (art) and traditional written literature. We can loosely call verse that merges the image and the text ‘Concrete Poetry’, and it’s oddly difficult to do this as well as Onsando does.

Concrete poems have a spatial existence as well as linguistic ‘meaning’, and lie somewhere ‘between poetry and painting’, as a critic once proposed. Certainly, Onsando’s example here, and others in the collection (such as a poem in which the word ‘up’ goes, well, upwards), present what can be called pictorial typography, or images produced by type, similar to what happens in Apollinaire’s famous concrete poem, ‘Il Pleut’ (‘It is Raining’), the text of which streams down the page.

Interesting about the font in Onsando’s poem is how ‘blistered feet’ is in a large, bold, solid-looking font; perhaps these are a labourer’s feet. ‘Manicured hands’, however, is in a stylishly curling font, perhaps suggesting elegance, class and wealth; manicured hands are not callused, are not the hands of a manual labourer. The word manicured ‘means’ cared for and classy, and the shape of the font supports this meaning, reinforcing it; image and text work together as what one theorist has perhaps prosaically called an ‘imagetext’.

When reading this poem, then, we might appreciate two worlds colliding: the poor young man and the rich woman. Disney’s The Lady and the Tramp, perhaps, or an episode of KTN’s Tujuane in which a streetwise young man from a poor background is patronized by a snobbish young woman with class-attitude. Perhaps the line break, then, represents the class divide? Perhaps this is how Onsando envisaged the poem. He has certainly said of Something Quite Unlike Myself that it is ‘about a class that is completely oppressing the class below it’.

It is no coincidence, perhaps, that Onsando has previously participated in collaborative projects that combine images (Kenyan photography) with text (Kenyan poetry) such as the online Koroga Project, which is worth Googling. It may well be that Onsando is becoming one of our more interesting poets in terms of breaking away from ‘pure text’ and spinning the word into other art forms.

From personal poems of inequalities in love, to poems considering more overt political oppression and violence (there are poems on extra-judicial killings and politician’s rhetoric), Onsando’s innovative verse uses font colour, style, size and fading to produce a huge diversity of meanings from poems that appear deceptively ‘easy’. This is great crossover poetry, then: generous to the reader new to poetry, and fascinating to the academic reader.

It is the type of poetry collection that leads this commentator to in turn say something very much unlike myself: to hell with the mainstream publishers, if they won’t publish innovative stuff like this, for independents like Onsando are able to do it better than you would have.

(Something Quite Unlike Myself is available at the Yaya Centre’s ‘Bookstop’, and from Amazon)