This is the (mostly unchanged) text of a talk I delivered at UT Austin, last Tuesday.

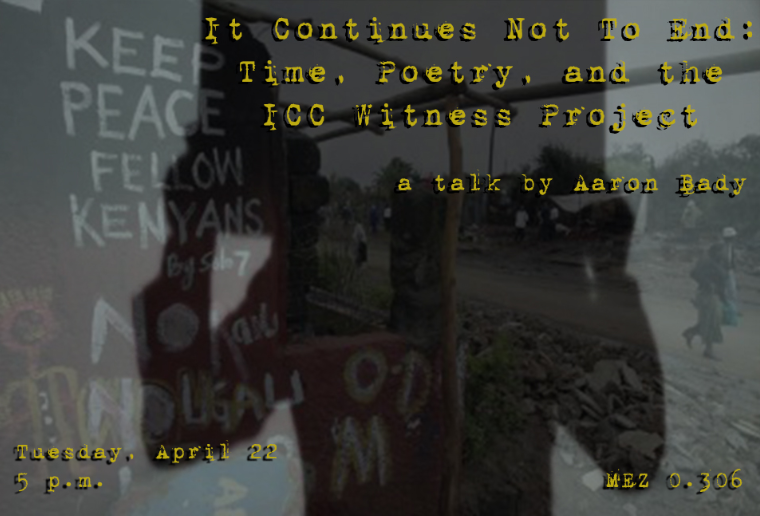

Today, I’m going to talk about the ICC Witness Project. This is an archive of poems written and posted to the internet over the last year, starting last March; there are over 150 of them now, with 144 titled as numbered witnesses— “Witness #1, Witness #2.”

The “ICC” refers to the “International Criminal Court,” where a prosecution is currently pending against the sitting president and deputy president of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto, for crimes against humanity committed in the Post-Election Violence of 2007, three months of wide-spread killing and burning across the country, that took on ethnic and gendered overtones and left about 1500 people dead, perhaps a million displaced, and countless thousands sexually assaulted. A church that was burned in Eldoret became one of the central images of the violence, killing those who were sheltering inside.

The expressed aim of the ICC Witness project is to speak for and with witnesses who have been intimidated into silence. But the ICC Witness Project is not a part of the ICC case, and the poets involved are not “witnesses” in the normal sense. Instead, the project very basically questions who counts as a “witness” and is premised on a radical destabilization of what witnessing mean. As an effort to represent voices which have been excluded from the ICC’s truth-making apparatus—modes of subjectivity which cannot be heard in its construction of justice—the term “witness,” itself, becomes an index of the many kinds of testimony which do not and cannot achieve official truth status.

The project is therefore a testimony to what several poems call “un-witnessing,” the manner in which the absent or retracted testimony of silenced witnesses is actually still present, present-as-absent.

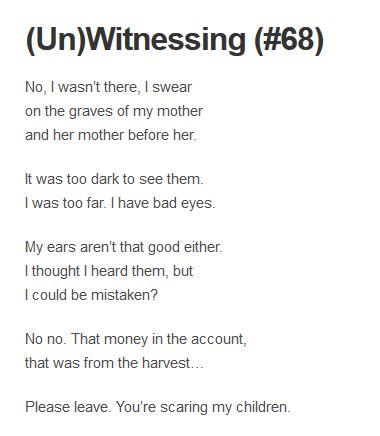

Witness #68, for example, testifies to having nothing to testify:

This is unwitnessing: testimony to the absence of testimony. Or as Witness #144 puts it, “un-witnessing is cooperation in the production of reality in which Uhuru Kenyatta is president..One of these realities will become true: either he will be convicted and cease to be president or he will be acquitted and cease to be the accused.”

This is unwitnessing: testimony to the absence of testimony. Or as Witness #144 puts it, “un-witnessing is cooperation in the production of reality in which Uhuru Kenyatta is president..One of these realities will become true: either he will be convicted and cease to be president or he will be acquitted and cease to be the accused.”

Witnesses who do not testify are un-witnesses because they testify to the official absence of a reality which remains subjectively true, even if it never reaches truth-making apparatuses like the ICC. I call the ICC a truth-making apparatus, by the way, because as the poems show, there is no way to opt out: because Uhuru Kenyatta is either president of Kenya or international criminal, un-witnessing becomes testimony to for the defense. In place of a constative report of what happened—a statement of what was witnessed—un-witnessing is a performative speech act indicating that nothing was witnessed, akin to the silence that follows the sentence: "if anyone can show just cause why this couple cannot be married, let him speak now or forever hold his peace.” Silence is forced consent to remain silent. Silence becomes what anthropologist Veena Das calls “poisonous knowledge,” in which containing the knowledge of the violation, in silence, is itself the expression of that knowledge.

The ICC Witness Project began in February, when this BBC article:

was shared on two listservs, the Concerned Kenyan Writers google-group and the Kenyan Poetry Catalyst google-group. The article concerns the slow-motion collapse of the ICC’s case, as its witnesses have been intimidated into silence. As Fatou Bensouda, the chief ICC prosecutor, has complained:

“The scale of witness interference in the Kenya cases has been unprecedented… the intimidation and interference goes beyond individual witnesses themselves and extends to pressures on their immediate and extended families, relatives and loved ones.”

The ICC has little to no provision for witness protection, and since the government of Kenya has actively sought to block the prosecution at every stage, anonymity has been the witness's only real protection. Kenyatta and Ruto are powerful establishment elites: Kenyatta is the son of Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, and the country’s richest man, and Ruto is the successor to Kenya’s second president as pre-eminent political leader within the Kalenjin community. Inn 2007, they were political opponents—and they are accused of fomenting violence against each other’s supporters—but the ICC charges gave them a shared interest, so they ran for president and deputy president under what they called the “jubilee” coalition, and last March, they won.

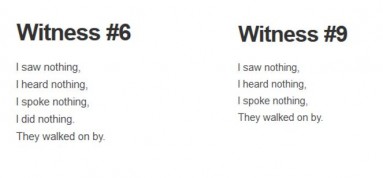

Before the election, about forty poems of what would become the ICC Witness Project had been written and privately circulated on the two listservs, but at that point it was an internal, private dialogue, limited to members of the list. Among those members, however, the poets were publicly known: the poems were titled as numbered witnesses, but they were also clearly identifiable by the email address of the sender. On March 9th, the day Kenyatta was declared the winner, the project went online as an act of protest. Now, however, they were publicly anonymous: no author names and no indications anywhere on the site who was behind it, other than “Kenyan poets, in Kenya itself and in the diaspora.” The poems that circulated on the listservs are stylistically all over the map. A number of them are structured by what I’d call narrative by subtraction;

Witness #9 is the same poem as Witness #6, except one line has been removed, and there are several others that play with this kind of aesthetic. But after the project went online, it takes on a more coherent voice, even as more poets became involved. Now anonymous, collective, a collective voice for the project begins to emerge, what I would characterize as: a ghostly subjectivity of a form of life which is not supposed to exist, and knows it, and which feels itself to be a problem to be solved, but for which no solution is possible.

Witness #9 is the same poem as Witness #6, except one line has been removed, and there are several others that play with this kind of aesthetic. But after the project went online, it takes on a more coherent voice, even as more poets became involved. Now anonymous, collective, a collective voice for the project begins to emerge, what I would characterize as: a ghostly subjectivity of a form of life which is not supposed to exist, and knows it, and which feels itself to be a problem to be solved, but for which no solution is possible.

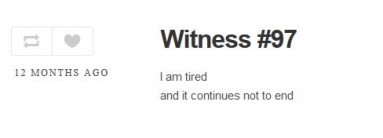

90 poems were online by the end of March, and another thirty by the end of June, and not nearly so many since. But the project does continue: a new poem was posted last week, and four new poems were posted between the time I taught the text in the fall semester and the time I taught it in the spring. This sense of openness is crucial, as is the manner in which we are forced to read it: we start at the end, and read backwards, into the past (perhaps something like Benjamin’s Angel of History). In this way, it not only responds to ongoing events in Kenya, but as events in Kenya go on, so does the project. Since Kenya “continues not to end,” the project cannot come to a close, cannot end its labor.

We need to do a kind of critical work to make this text legible. The ICC Witness Project is a digital project, which uses poetry to perform an intervention into how Kenyan history is told, so I’m going to structure the remainder of my talk by these three frames of reference: the digital, the historical, and the performative. These frames overlap and bleed into each other, of course, but the structure allows me to give a sense of the different stakes of the project.

First, the digital: The ICC Witness Project is a digital artifact, or a digital archive, or a digital project; each of those terms captures an important aspect of what it is, and my inability to settle on only one speaks to the formal innovations which the digital medium enables, which I’ll discuss. I’ll also place this text within the digitization of Kenyan and African literature more broadly.

Second, the historical. This text is very much of a particular moment in Kenyan literary culture, what I would characterize as the disillusionment of the post-Moi period. When Moi left power in 2002, there was a real burst of enthusiasm around the new beginning for Kenya it was seen to represent, but in both form and content, the poems testify to the deepening repression and violence of the present, what many fear is a return to the past. It also demonstrates a schism that is emerging within the Kenyan literary community: those who hew to an “Africa Rising” narrative of a country on the move—putting its past behind it, and striding optimistically into the future—and those whose sense of the present is of a past that will not stop happening, which continues not to end.

Third, the Poetic, or Performative. Discussions of human rights literature tend to privilege narrative realism, and authenticated legal testimony is perhaps the ultimate form of narrative realism. Poetry can be realist and narrative, of course, but I will argue that this poetry performs its antagonism towards narrative History by its formal aesthetics—its non-narrative, non-prose form—and by the way its forward movement is chronological without being teleological: time is an oppressively repetitive sequence, not a progression towards resolution or transcendence. But performance allows static time to become an artifact of human expression, malleable and social. So I’ll close with a few words on what I’m calling the social life of this poetry: the manner in which a different chronology than mere repetition emerges from the circulation of these poems as a shared text for performance. These are, ultimately, poems which testify to the forms of human life which cannot be recognized as human, which are available for genocidal imaginations. But as performance, the project strives to make such forms of life thinkable and livable, to create community out of atrocity.

I. The Digital

Valorizations of the digital are often ahistorical celebrations of modernity’s transcendence of the pre-modern, and often obscure the ways modernity is structured by continuity with the past. The digital is often taken to be another Gutenberg moment. But African literary history reminds us that things are more complicated than that: in Africa, a fetishization of oral literature was a decisively post-print development, a renewal of interest in orality as a cultural alternative to the various print-literatures that were tainted by their colonial origins. It was print culture, in other words, that made “orality” newly important.

Something similar is true for African digital publishing: “online” is not a transcendence of the print form, but a development within it, and made legible as such only by a crisis within print culture itself.

Kenyan literature, for example, is experiencing a literary renaissance right now, and digital media are a crucial part of it.

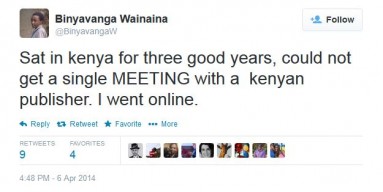

Binyavanga Wainaina, for example, has been at the center of the the post-2002 proliferation of new Kenyan writing and all of his early writing was born online—including much that would later be published in print—and the viral circulation of his essay “How to Write About Africa” allowed it to reach an audience exponentially larger and for a much longer time than the original Granta print run. You can’t find it in print even if you want to, though there is a print version available in Kenya; but everyone’s read it online. It’s an incredibly influential document; citing it is almost second nature, and it continues to circulate. People still email it to me.

More generally, some of the most interesting and innovative new writing I’ve seen from Kenya has been online: the ICC Witness Project, for one, but also the Jalada writers collective—whose anthology is coming out soon as an e-book—a site called Brainstorm Kenya, which just released an important e-book on Kenyan feminisms, #WhenWomenSpeak, and the project which most immediately precedes the ICC Witness Project and overlaps with it, the Koroga project, a tumblr series of images and texts.

In a broad sense, I would suggest that the digital has become central to African literary production for many reasons. One is that it allows writers and writers collectives to sidestep traditional literary gatekeepers, a fact that is particularly crucial in places where publishing and academia have become sclerotic and nepotistic, and sometimes, to evade state censorship. But it’s also a simple function of economic obstacles like the expense and high start-up costs for print-based publishing.

For example, when I asked one of the ICC poets what kind of poetry he read, she answered,

“whatever poets I can find...I grew up on old white men but recently moved my reading to people of colour. The thing is though, it's very hard to get poetry books here. So I mainly rely on blogs and such.

And she named a few, both personal blogs—with both copied and original work—and sites like Poetryfoundation.ord.

In this sense, the digital is not “post-book.” Situating this archive within its digitized 21st-century context does require accounting for changes in the textual ecosystem that have occurred over the last few years, but the timeline is not two-dimensional: history is always layered and develops unevenly across geography. To understand what the ICC Witness Project says that is new—and to frame why it says it this way—we have to place that novelty within a specifically African and Kenyan context, where, for example, old white men books are available, but poems by people of color circulate online.

This is the particular “history of the book” that obtains there, so let’s move to the historical, historicizing the digital.

II. The Historical

The ICC Witness poems were written and circulate online, but “online” is only meaningful within a textual ecosystem that still gives the printed word a pride of place and that defers to the authority of the authoritative text. The ICC Witness Project’s subordinate relation to “the book” is part of what makes it a subaltern form. Precisely because these poems do not aspire to the status of authoritative text, they are not texts that easily accrue legibility, cultural capital, or authority. Anonymous witnesses lack testimonial authority, for one thing, and if “realism” marks discursive claim to some kind of empirical, objective validity, then these poems are, as poems, subjective and decidedly anti-realist.

At the same time, the kinds of texts which do accrue legibility, capital, and authority are implicated in the political imperatives of the post-Moi moment, a literary moment dominated by the NGO and civil sector, and by the forms of writing which it produces. The poet and critic Keguro Macharia called this form of writing “Report Realism” and traced the imperative to report to the rise of the NGO-industrial complex in post-Moi Kenya.

“Over the past 15 years and more specifically the past ten years or so, Kenyan writing has been shaped by NGO demands: the “report” has become the dominant aesthetic foundation. Whether personal and confessional or empirical and factual or creative and imaginative, report-based writing privileges donors’ desires: to help, but not too much; to save, but not too fast; to uplift, but never to foster equality…The believable and the realistic are bounded by NGO narratives and perspectives. And too many writers believe that the only writing worth anything is the believable and the realistic: to be a “committed” writer requires adhering to report realism. Report realism believes in the power of “truth,” whether contemporary or historical, with a faith that borders on fundamentalism. In report realism, the truth will set us free.”

The first poem in the ICC Witness project deconstructs this mode of realism:

As the first poem in the series, this sets the tone for the project, not because of what it reports, but because of what it doesn’t, and can’t. “They killed my family” is a painfully direct report of a horrific event, in painfully simple words. But these four words, three lines, two stanzas, and one poem are such a forced constriction of form to the production of a report—the fact that the speaker’s family was killed by “them”—that the poem collapses the very discursive structure through which it might signify. It reports everything and nothing, and this is its provocation, which started the project moving. This is the fundamental truth of the witness—and in the broader sense in which “Family” speaks to the dismembering of the Kenyan national family—it reflects the ways intimate violence was also political, and political violence was also intimate. But in reporting what happened it performs the inadequacy of doing so. To the extent that it is true of everyone in Kenya, it is true of no one in particular.

This kind of reality is something which the many commissioned official reports on the Post Election Violence have been unable to address. The Waki commission produced a report which jump-started the ICC prosecution, and a Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission was established to determine what the long-term causes of the violence had been. But these truth-making processes have run their course and accomplished little, beyond producing enormous authoritative reports. The government has barely even bothered to repress them; without a political will to revisit the past, they are meaningless. The TJRC report is, itself, a kind of un-witness. Its recommendations carry the force of law, but the government of Kenya has simply pretended it doesn’t, and ignored it. That becomes the new truth as a result.

But the conclusions of these reports helps produce a sense of history as finished, as settled, and this might be the crux of “report realism,” the way it produces a sense of time, the finality of a reality which has been reported on. This is the narrative which Kenyatta and Ruto have taken their electoral mandate to have ratified, the fact that “Kenya is moving on.” At his victory, Kenyatta declared that

“This year marks 50 years since the birth of our nation – this is our jubilee year. As the Bible tells us the year of the Jubilee is the year of healing and forgiveness. It is the year of renewal. My brother William Ruto and I were once on opposite sides but we agreed to put our differences aside and come together as leaders to end this cycle of violence and bring enduring peace, this has been our Jubilee journey.”

Impunity for perpetrators, however, is barely even subtext; on the eve of the election, Kenyatta told Al-Jazeera, explicitly, that “if Kenyans do vote for us, it will mean that Kenyans themselves have questioned the process that has landed us at the International Criminal Court.”

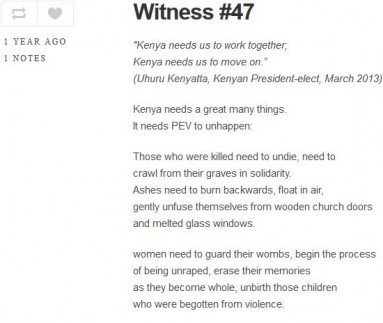

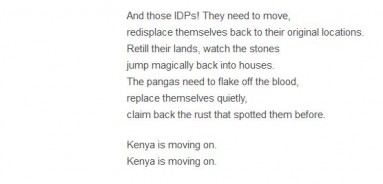

Witness #47, I think, is the poem that most clearly articulates the poetic retort:

It begins with Kenyatta’s own words, but in the voice of the president, the statement of “need” becomes an imperative, a governmental command. Yet the poem highlights the absurdity of this official fantasy: moving on seems to literally require moving backwards. Victims are healed by using machetes to re-attach severed limbs, stuffing children back into their wombs, and watching as scattered stones and rubble magically rises to construct houses, which promptly unburn themselves up from the ground.

Note that this magical healing is a burden placed on the victims, a “need” which is a command:

- Those who were killed need to undie

- women need to guard their wombs

- [women need to] erase their memories

- And those IDPs! They need to move

The roadblock to moving on is the victims whose continued existence (as victims) stands as the obstacle to amnesia. And IDPs—an acronym meaning internally displaced persons—remain as the residue of the violence, the mess that has been left over, and which it is the job of the government of Kenya to clean up. Or, in government and NGO speak, “to integrate.” However, to integrate IDPs is to solve the problem by making its subjects disappear: as IDPs become the logistical problem of “integrating” them into new communities, the problem is solved when they cease to be IDPs. A report from last year reads, for example, that “Out of the more than 660,000 people displaced, the government considers that over 300,000 or around 47 percent have been ‘integrated’ in communities across the country.” Kenya’s progress, then, is measured by the number of IDPs that do not continue as IDPs; Kenya moves on when IDPs move on.

In the reality that statistics don’t measure, of course, violence that cannot be construed numerically still exists. What statistics don’t measure, to paraphrase, is how it feels to be a problem. There was widespread sexual violence during the PEV, for example, but such violence is not conducive to statistics, and as a result, a focus on statistics effectively un-narrates the forms of violence which leave their victims alive, especially true when victims are socially stigmatized. The truth often does not set rape victims free, or men who have been castrated or forcibly circumcised, a category of victim for whom public tribunals are particularly ill-suited, and in many cases, an exacerbation of the original violation.

By the final refrain of witness 47, then, “Kenya is moving on,” we see the hidden violence of time: the labor of moving on is placed on the shoulders of the victims, whose responsibility it is to erase themselves as victims. As they “crawl from their graves in solidarity,” one might say, they have a patriotic duty to not be dead. Yet this un-doing only exacerbates the original violations, a traumatic repetition. As the injunction to move on rehearses each category of victim—killed, raped, displaced—we relive the instant of the violation. To assent to the official fantasy, the dead must rise from the grave like zombies. If you fail to perform the miracle, you are a failed subject.

While poems like Witness #47 directly satirize the Jubilee narrative, many more of the poems describe how it feels to be a problem, speaking from the position of a trauma that can find no public expression. This ghostly non-existence—the feeling of being out of place with the nation narrative, lagging behind as Kenya moves on—gets expressed in a variety of poems in which witnesses apologize for their existence.

Witness #122 writes “we are sorry for being roadblocks on the highway to national reconciliation”

Witness #49, begins:

Move on,

They tell me.

Why can’t you

forgive,

pick yourself up

and move on?

I’m sorry if I offend you…

And Witness #129 writes

We are very sorry that the president

(and his deputy) were involved

in not committing these crimes:

We are sorry that Wanjiku acted

of her own accord, when she gathered

her children in a burning church;

Reality is, however, more absurd than fiction: on October 25—well after these were posted—K24TV tweeted the following, a quote from an actual ICC witness in court:

Witness: I am sorry if I offended anybody in my appearance in this court. I am sorry. #ICCTrialsKE

This tweet, however, has since been deleted. I remember seeing it—as you can imagine, it caused quite an uproar—but in going back into the archive, I couldn’t find any trace of it. Instead, it only exists because Shailja Patel, a Kenyan poet, re-tweeted it, and because of various other commentaries and exclamations of horror and disgust. The voice of that witness, such as it is, can only be heard through the fossil of its suppression.

I want to close, now, by talking about how poetry becomes performance, how texts becomes vital. If the project begins with the genocidal imagination that turns people into problems, victims into numbers, and statecraft into violence, the poetry achieves its goal when it turns textual reports into lived subjectivity. A crucial part of the project, then, is what happens after it has been written, the modes of circulation by which the poetry works its way into the social life of the nation.

III. The Social Life of Poetry

Officially, the poets in this project are anonymous, with some limited exceptions. Within the archive proper, however, anonymity is an important fictive component of the project. I use the word “fictive” because it involves a suspension of not of disbelief, but of knowledge. This seems to have applied to the poets themselves; as one told me (but many said something similar):

“part of the mental model of preserving the anonymity of some of the writers has actually made me 'forget' (at least, temporarily) who wrote what…looking at the older email threads has revealed the poets again, but I know there are times I've looked at the project and failed to recognise even my own voice”

As this poet acknowledges, there exists a relatively clear record of who wrote what, in hundreds of inboxes, including mine. I have access to many of the original emails, because I’ve been a member of the CKW google-group since last July. But it’s easy to pierce the anonymity of the process, because it wasn’t very anonymous, originally. Anonymity was added in, after the fact, at the precise moment when Kenyatta and Ruto were declared the winners of the election, when the poetry went online. The effect was to take a digital dialog between poets who know each other, and are fairly well known, and to turn it into a single first-person plural sequence, voiced by a national subject who witnessed the violence, in the broadest sense of the word. As one poet put it,

“anonymity allows us to be a collective of poets writing beyond whatever categories of difference ostensibly divide us. I'd like us to think of how our collective art can provide a space and method for being together as Kenyans.”

Anonymity de-individualizes the poets whose names might mark them as less Kenyan that Kenyan; as with most Kenyans, the poets all have names which activate stories about ethnicity and gender, which would tempt the reader to read them in particular ways: Male Muslim, Kikuyu woman, etc. Anonymity removes that temptation; in practical terms, it enables a form of sympathetic identification that ethnic and gender marks could preclude. To go back to the first poem, “They killed my family,” a Kalenjin whose family was killed by Kikuyu can identify with a Kikuyu whose family was killed by Kalenjin. And any Kenyan who felt that post-election violence killed the Kenyan national family—a common way to construe it—could feel implicated in the poetry.

Put differently, when the poetry is voiced anonymously, it speaks a national subjectivity defined only by the experience of witnessing PEV, and by how it feels to be a problem, the problem of being forced to do the impossible, to cease existing.

I’ve taken my title from Witness #97, which reads:

My talk is almost over; if you’ve been watching the clock, then be cheered: it will only continue not to end a little longer.

My talk is almost over; if you’ve been watching the clock, then be cheered: it will only continue not to end a little longer.

But as the experience of academic talks often shows us, time can be labor. The poets I’ve talked to are exhausted. The election is over, the TJRC is over, the ICC case might be over, and the Jubilee narrative insists that any hope of justice or reparations for the victims is over. Closure is officially mandated from on high, and especially because the election seems to represent a kind of broad, apparent acceptance of the status quo, across much of Kenyan society, it also represents a way in which the Kenyan “family” has been killed, metaphorically; one poet described wanting to “divorce” Kenya, but being unable to do so.

In this sense, the openness of the form reflects the refusal of the wound to close on its own: each poem is an instant in time, but they do not resolve into a story, only an interminable unresolved and plural present. There is no closure or resolution immanent to the text itself.

There is, however, a progress narrative that you can tell about the poems as they circulate. These poems were performed at World Cafe at the Hague, on the eve of a trial hearing, and a version was performed at the Storymoja festival in Nairobi; some of the poets, I know, are planning another performance. These performances are acts of world-making, imaginations of community. One of the poets involved in the performance told me that:

“I cannot, now, think of this poem without thinking of @Zinduko’s choreography (unrecorded) of its performance. some of the poems you’re interpreting are now kind of “muscle memory," associated with spaces of rehearsal and sites of performance (houses, theaters, gardens, museums)”

I’ve heard more than a few variations on this sentiment. The poems have become a common text, to be adapted and used, re-set, re-interpreted, and re-circulated (something which the internet particularly facilitates). As texts they testify to the injustice which has occurred. But as spaces of performance and association, they become public imaginations of community, new ways of performing Kenyanness through witness and solidarity. As performed—and as the performances are witnessed—they testify to the un-un-witnessing of the many Kenyans who have been un-witnessed. They demonstrate that others also remember, and they help to produce a different common sense than the official narrative of Kenya on the move; PEV becomes something that binds Kenyans together in structures of intimate relations, rather than the structures of negative ethnicity and misogyny which make some forms of like killable, un-grievable.

Finally, in the context of an increasingly repressive media atmosphere in Kenya, an important part of the project has been to test the waters and see if such things could still be said. The Moi years were a period of violent repression, and his departure twelve years ago was to mark a change. With Kenyatta’s presidency, it’s far from clear that that is still the case; government harassment of journalists and activists is both official and bureaucratic and seems to be escalating. As one of the poets put it, “Suddenly, for the first time in a long time, we couldn’t assume we still officially possess the freedom to speak. The ICC Witness project is a way to take – and test – that freedom.”

After all, if free speech, political association, and the right to assemble to demand redress of grievances are fundamental civil rights, they are also, always, only a promissory note, up until the check is cashed. In that sense, while the ICC Witness poems individually attempt to recall and remember the moments of past trauma, and to testify to stuck-ness of the present, the project, as a whole, actually is a project of moving forward, through the work of calling into existence a Kenya where such things can be remembered as something that will not continue to happen.

Thank you.