Frédéric Lordon's Willing Slaves of Capital helps clarify how two of the fantasies that feed neoliberal ideology — liquidity and authenticity — interrelate. The two concepts represent two opposing faces of the same hyperindividualism around which neoliberalism is organized. (Liquidity: I want to do whatever whenever; authenticity: who I am is inviolate and is all that really matters.) As we become the atomized, entrepreneurially fixated personal-enterprise selves that neoliberalism prompts us to be, we are supposed to be so flexible as to be molded into suiting whatever profitable opportunity comes along, yet we are also expected to be entirely invested in our activity and derive pleasure from the presumed autonomy we have in "choosing" to be molded or to mold ourselves. Under neoliberalism, workers must be authentically liquid; their "real selves" must also be infinitely malleable.

Lordon defines "liquidity" in much the way I typically define "convenience" — a fantasy about "never having to take the other into consideration":

Keynes had already noted the fundamentally anti-social character of liquidity, as the refusal of any durable commitment and Desire’s desire to keep all options permanently open – namely, to never have to take the other into consideration. Perfect flexibility – the unilateral affirmation of a desire that engages knowing that it can disengage, that invests with the guarantee of being able to disinvest, and that hires in the knowledge that it can fire (at whim) – is the fantasy of an individualism pushed to its ultimate consequences, the imaginative flight of a whole era.

When convenience is trumpeted as a value, it's really celebrating this kind of antisocial flexibility, the refusal to commit to any project and privileging instead the ability to switch at a moment's notice to a more profitable alternative. Lordon argues that "liquidity in the narrow sense (financial liquidity) acquires a broad signification: the unconditional right of desire to do as it pleases." It is a fantasy about money becoming pure potency, pure potential. Convenience reflects this same dream of noncontingent possibility, of being entirely self-reliant when it comes to pleasure, as if pleasure wasn't intrinsically social. When we demand that life be convenient, it suggests that we have so throughly identified our lives with money that we want to become it.

As personal desire gets moneylike, it becomes noncontingent, unconnected to any embedded circumstances or established social relations; it is "free" to be redeployed and put to use to valorize any activity. Once these "joyful affects" are free-floating, they can be attached to any task and also be demanded from employees at any time. Their "authenticity" can no longer be anchored in particular situations but can be requested on demand. Authenticity becomes an effect of power.

Hence, Lordon configures authenticity not as the basis of a kind of resistance to power (or servitude) but as the ultimate mark of obedience to it. The concept of one's "true self" only appears as a knowable, consciously considered thing in order that it may be remolded to suit capitalism's demands for the totality of one's productivity. Authenticity, then, should not be seen as a personal goal but as a employer demand. Or rather: If you are consciously pursuing the goal of authenticity, it's because a job (or some desperate freelance pursuit of human capital) is forcing you to.

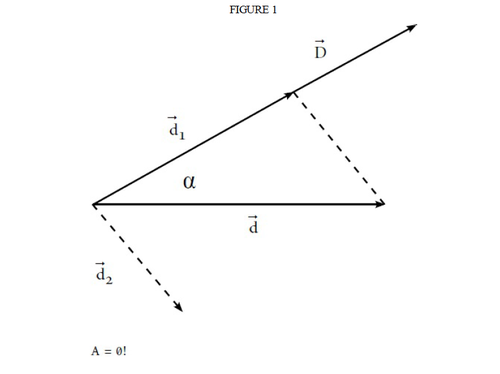

Under neoliberalism, Lordon argues, employers have enough leverage to insist that workers' desires align completely with that of employers, so that all their life force essentially goes into enterprise. He even provides this somewhat unnecessary Lacan-style chart to illustrate it:

The goal of neoliberalist employers is to make d1, employers' "master-desire," and d2, the conatus of the workers, align completely (making the divergence between them, a, equal 0!). This is mainly a matter of getting workers to identify fully with their job, to see work as the forum for self-fulfillment ("meaningful work") and to accept obedience as a kind of autonomy or volunteerism.

The strength of the neoliberal form of the employment relation lies precisely in the re-internalization of the objects of desire, not merely as desire for money but as desire for other things, for new, intransitive satisfactions, satisfactions inherent in the work activities themselves. Put otherwise, neoliberal employment aims at enchantment and rejoicing: it sets out to enrich the relation with joyful affects.

In other words, neoliberalism hinges on making people work for love rather than money. You don't work for money, you work to be money, and you love being so useful.

But as with all things neoliberal, the burden for making this motivational shift falls on the employees: To qualify for jobs, workers have to convince prospective employers that they want to work not just for the money but because they yearn to be, or already are, what the job description details. Upper-echelon managers have already bought into this subsumption of self to work: Lordon cites Bourdieu's remark that "the dominators are dominated by their very domination" — they are constrained to believe their own bullshit. But now all workers need to make job tasks seem like things they spontaneously wanted to do anyway; they have to perform an implausible enthusiasm that seems more and more ludicrous the more employers expect it. After all, once one level of enthusiasm is performed, a more intense level must be reached for the next show to be persuasive. Lordon suggests some of the dilemmas this presents for capital — having its prospects for growth hinged to total affective control: "This enlistee swears that he has no other passion than the manufacture of yogurt, our company’s business, but can we unreservedly believe him?"

Pret à Manger notoriously demands this kind of excitement from its fast-food workers (they are supposed to smile and make small talk with customers and rate other employees in terms of their team spirit and so on) — in Lordon's words, such employers aim for "the ultimate behavioral performance in which the prescribed emotions are no longer merely outwardly enacted, but ‘authentically’ felt." They have to smile and "really" mean it. They have to eradicate pretending, eradicate the gap demarcated by the concept of "service" and sell the pretense that customers and servants are equal, only the servant has graciously and eagerly volunteered to kiss the customer's ass.

This demand for observable total commitment puts employees in a "double bind" in which they have to "manufacture artlessness." Since no one can actually succeed at this, it means that (1) workers are always having to work hard on their emotional disposition without ever achieving the goal, and (2) they can always be disciplined or terminated for failing to successfully be emotionally "real." Again, what is "real" is determined not by your inner feelings but by those who have the power — in this case, employers who can withhold the means for survival. The discourse of authenticity involved with this coercive arrangement becomes its alibi: It attaches a veneer of consent to forced labor, offering a framework through which employees can adopt the demands placed on them as their own real desires.

Capital has taken to forcing the obvious contradiction of "acting authentic" on labor because, Lordon argues, it has the leverage to get away with it. But will sustaining that contradiction prove too much of a burden for workers? Will it give shape to a means of resistance beyond "being real" or "being true to yourself"? Neoliberalism teaches subjects to both demand individual autonomy to choose who they want to be and to be flexible enough to be molded by the flux of larger profit-seeking forces. And it expects workers to bear the burden of resolving those demands' incoherence and find joy within them. Lordon points out that this is a risky, unstable approach to social control: to construct subjects who understand themselves as genuine and unable to be socially constructed. At what point does that kind of construction become too effective?