Advertisement from Oral Hygiene (1922)

Temptation rides a whiff of ether in Frank Norris's McTeague (1899). The novel relates the romantic adventures of its title character, a San Francisco dentist who falls in love with Trina, a young lower-class woman who visits him for treatment of a carious tooth.

Upon inspection, Trina's painful bicuspid presents McTeague with a problem. The tooth's extraction would most certainly mar "the pretty mouth"

"Draw thee towards Him, that thou mayest proclaim / With how many teeth this love is biting thee" --Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy: Paradise

housing it, he concludes. No, the situation calls for action altogether more delicate. Capping the offending tooth offers the best solution. Use of "bayonet forceps" to force the tooth's roots into "a flattened piece of platinum wire" will be necessary. On this tricky procedure depend not only a young lady's fine looks but his professional reputation as well.

The operation proves as time-consuming as it is delicate, taking a fortnight to complete, and the performance McTeague puts in is anything but virtuosic. Though he admits "he bungled it considerable" at certain points, all in all "he succeeded passably well." Through this process the patient trooped admirably on. Trina came "nearly every other day, and passed two, and even three, hours in the chair."

"Caries of the teeth is unusually common among the insane," observes Theodore H. Kellogg in A Text-Book on Mental Diseases (1897), "and in the toxic insanities a specially constant symptom."

Spending so much time with a girl of Trina's age was quite out of the ordinary for McTeague; with each visit to his office tender feelings toward her grow in him. He finds opportunities to observe her closely. He notices in her nothing of the shop girl or "the young women of the soda fountains." A man of plain, uncomplicated principles, he values this. Yet he takes a slight liberty. He extracts a small tooth, which he wraps "in a bit of newspaper" and drops in his vest pocket as a memento. Under anesthesia, so "helpless, and very pretty," Trina senses neither this theft nor the passion behind it.

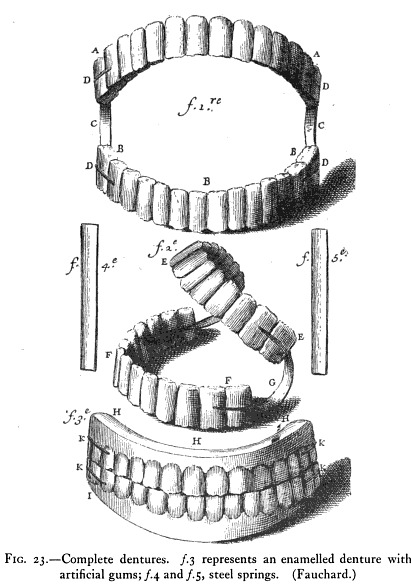

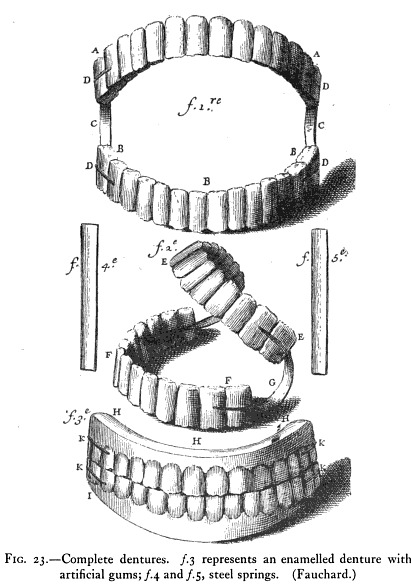

Illustration from Vincenzo Guerini's A History of Dentistry from the Most Ancient Times Until the End of the Eighteenth Century (1909)

Like ether, the affection burgeoning in McTeague escapes his office for the more appropriately pastoral environs of Schertzen Park. Herself taken with her dentist and eager to test his handiwork, Trina invites him to join her family for a beach picnic

"German pretzels are made from a dough raised with yeast, and just before baking the strips are plunged in boiling water in which oat straw is soaked," writes Edgar Henry Summerfield Bailey in Food Products (1921). "After salting heavily the pretzels are baked quickly, and then allowed to cool slowly in a warm oven."

. "What a day that was for McTeague!," the narrator exclaims, registering his subject's joy. "What a never-to-be-forgotten day!" The day indeed passes unforgettably. The lovers play and laugh together while Trina's family, the Sieppes, pry clams from the mud. Later, they all gather for an elaborate lunch. Trina and her mother prepare "a clam chowder that melted in one's mouth" accompanied by "huge loaves of rye bread chock full of grains of chickweed" and pretzels. On the picnic cloth wiener-wurst and frankfurters glisten, as does "cold underdone chicken, which one ate in slices, plastered with a wonderful kind of mustard

"The German mustard gas has a mustard smell, while the Allied mustard gas, due to a slight difference in the method of manufacture, has a very perfect garlic odor." --“Gas in Defense" (1920).

that did not sting." Mounds of dried apples and "a dozen bottles of beer" are on hand to cleanse the palate, and dessert comes in the form of "a marvellous Gotha truffle."

The feast lasts two hours. Afterward, the one lover, "stuffed to his eyes," drowses over his pipe, "prone on his back in the sun," while the other washes his dishes. This seaside idyll marks the beginning of the couple's courtship. "McTeague began to call on Trina regularly Sunday and Wednesday afternoons," the reader learns.

Sublimity often takes root in something mean, like a cowslip in dung, a lily in mud--or love in a rotten tooth.