Some colonial women held captive by Native American tribes found the experience liberating

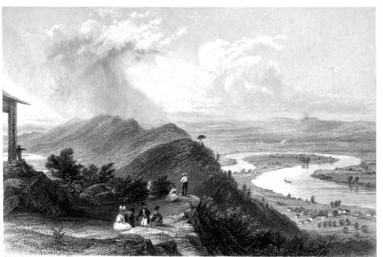

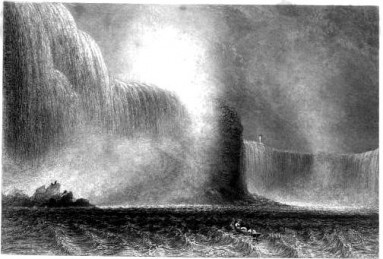

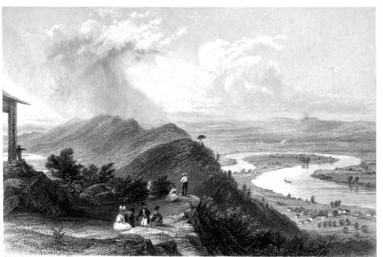

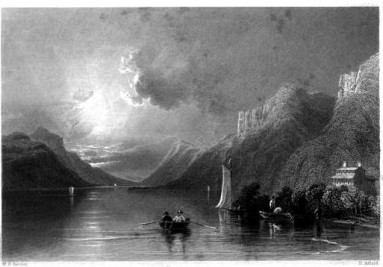

Illustrations from American Scenery; or, Land, Lake, and River Illustrations from Transatlantic Nature (1840)

One clear spring afternoon in 1758 a raiding party descended on the Jemison farm in western Pennsylvania. The party, which consisted of six French soldiers and four Shawnee warriors, managed to capture all the family members except the two oldest sons, who escaped. "Every one trembled with fear," one Jemison daughter, Mary, later recalled in her 1824 account of the event. Without “a mouthful of food or a drop of water” they marched until nightfall. Whenever Mary and her siblings cried for something to drink, they were told they may have urine or nothing at all.

"Conscience welcomes the Other."--Emmanuel Lévinas, Totality and Infinity (1961)

The Jemisons' captors began to think that they had taken too many captives. Mother and father, along with two of their children, were led behind some trees and killed, their scalps left to dry by a campfire lit later that evening.

Mary was spared. Her captors judged her young enough to adopt. Several hours after losing her parents she had her feet fitted with moccasins, her hair combed, and her face colored red with clay. She was given to two Iroquois women who the year before had lost their brother in the French and Indian War.

Custom dictated that the sisters be compensated in the form of an enemy scalp or captive.

"His spirit has seen our distress, and sent us a helper whom with pleasure we greet," the sisters cried. "Let us receive her with joy! In the place of our brother she stands in our tribe."

"Sister is probably the most competitive relationship within the family, but once the sisters are grown, it becomes the strongest relationship." --Margaret Mead

Mary describes her adoptive older sisters as “kind, good-natured ... peaceable and mild in their dispositions,” noting that they were “temperate and decent in their habits, and very tender and gentle” with her. Their settlement sat near the Ohio River. There the tribe and she planted and harvested corn. When necessity dictated, they moved to the forests along the Scioto River to hunt elk, deer, muskrat, and beaver.

There is pleasure in the / pathless woods, there is / rapture in the lonely shore, / there is society where none intrudes, / by the deep sea, and music in its roar; / I love not Man the less, but Nature more. --Lord Byron, Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812)

Except for one incident early in her time with the tribe, in which she felt overcome by "an unspeakable anxiety to go home" with some Englishmen she encountered near Fort Pitt, Mary never thought of escape. She grew to love her sisters and her life with them.

Mary even forgave the murder of her family, for it accorded with the tribe's idea of justice.

“Our labor was not severe,” she insisted. It was also reliably consistent, being “of one year ... exactly similar in almost every respect to that of the others, without the endless variety that is to be observed in the common labor of the white people.” Tribeswomen had to gather fuel for baking bread, a responsibility which Jemison deemed as "probably not harder than that of white women, who have these articles provided for them.” Indeed, compared to their white counterparts, the women of the tribe boasted cares “not half as numerous, nor as great.” Even tending the corn crop proved relatively undemanding. Jemison notes that she and the other tribeswomen “had no master to oversee or drive us, so that we could work as leisurely as we pleased.” This system allowed everyone to work together without inciting “every jealousy of one having done more or less than another.”

Relations between the sexes were of a similar cast. When told she was to marry, Jemison admits that she was initially reluctant: “Sheninjee was an Indian; the idea of spending my days with him at first seemed perfectly irreconcilable to my feelings.” She quickly changed her mind, however, when she discovered that her fiancé was "elegant in his appearance, generous in his conduct, courteous in war, a friend to peace, and a lover of justice." Most importantly, he was a tender friend. “Strange as it may seem,” she confesses, “I loved him!”

The final years of her long life Jemison spent as a member of the Seneca nation,

Jemison died at age 90.

her peace of mind disturbed only by occasional memories of her parents. "Had I been taken in infancy," she said, "I should have been contented in my situation." Jemison wasn’t alone in preferring the company of Native Americans. A similar sentiment pervades Lydia Child’s 1824 novel

Hobomok, in which a white woman willingly marries an Indian chief after her fiancé is lost at sea. "I speak truly when I say that every day I live with that kind, noble-hearted creature

Child's heroine, however, does eventually leave her husband.

, the better I love him," Child’s heroine says of her husband.

Riches many tribes considered not what one could horde, but what one could give away. Regular charity festivals ensured that widows were fed and their children cared for. “Hunger and destitution could not exist at one end of an Indian village or in one section of an encampment while plenty prevailed elsewhere in the same village or encampment,” observed Lewis Henry Morgan.

Though everything from Stockholm syndrome to desire for “the other” has been invoked to explain the allure of Native American society for white women, much of what Jemison observed has since been substantiated. Many Native American tribes developed far more just and democratic economic systems than were found in the colonies. The work of planting and harvesting, as Lucian Carr notes in his studies of New England Indians, was neither onerous nor compulsory, resembling more “the husking, quilting, and other frolics of their English neighbors” than any drudgery. Apportioned equally, work was carefully organized so that no one would grow jealous of her neighbor’s duties. Afterwards the laborers were feted by the families who owned the land.

"At a 'Farming with Dynamite' demonstration, held under the auspices of the Norfolk and Western Railroad, at Ivor, Va., on August 11, 1910, one and one-half acres, containing forty-six stumps were cleared in one day, at an expense of $18.00, including labor, or an average of 39 cents per stump." --from Farming with Dynamite (1911)

Ownership of land itself was based on sound principles. Among Native American tribes loomed no landed elite. Their economic system did not create many of the rent-seeking opportunities that always seem to precede social decay. Title to land was contingent on use. Each individual enjoyed secure right to as much unoccupied land as he could plant, so long as he continued to care for it.

"Property has its duties as well as its rights." --Thomas Drummond

Allowing his land to lie fallow threw it open to other comers. At any rate, most Native Americans regarded land as a common possession of the tribe. That it might be a single person’s private property was simply inconceivable.

Use-contingent ownership ensured that the land remained productive. From it came three kinds of corn, as well as pumpkins and squash. And the forest, with its abundance of ground nuts, persimmons, plums, grapes, berries, and maple, stood by to relieve the fields of some of their burden. Carr writes that the Native Americans made a milk of hickory nuts “as sweet and rich as fresh cream.” Acorns

"Everything on the earth has a purpose, every disease an herb to cure it, and every person a mission. This is the Indian theory of existence." --Mourning Dove

they transformed into bread and broth, soaking them beforehand in lye to remove their bitter taste. Wild rice they made into thick, nourishing porridge. Perhaps their most curious treat they made from unripe corn that they had sunk in stagnant water for two or three months. Thoroughly rotted, it was said to stink like nothing else.

Skilled hunters, Native Americans supplemented their diet of nuts, fruit, and grain with deer, bear, elk, beaver, buffalo, turkey, seal, oyster, shellfish, and snakes. They hunted everything in its season. Spring brought clouds of smelt to the rivers so thick that one could not put a “hand into the water, without encountering them,” as one anonymous source put it. Alewives, sturgeon, and salmon followed soon after. Large ducks called bustards appeared with the crocuses, their eggs twice the size of chickens’. No season lacked its delights. “It is a strange truth that a man shall generally find more free entertainment and refreshment amongst these Barbarians, than amongst thousands that call themselves civilized,” one traveler remarked.

"The old Russian Government established courts of law in the Aleutian Islands, but in fifty years those courts found no employment. 'Crime and offenses,' reports Brinton, 'were so infrequent under the social system of the Iroquois that they can scarcely be said to have a penal code.' Such are the ideal -- perhaps the idealized -- conditions for whose return the anarchist perennially pines." --Will Durant The Story of Civilization, Vol. 1: Our Oriental Heritage (1954)

Yet many observers noted also that many Indian tribes never stored much food for winter. The Jesuit Chrétien Le Clercq remarked that the Indians he lived among were convinced

that fifteen to twenty lumps of meat, or of fish dried or cured in the smoke, are more than enough to support them for the space of five to six months [and this] exposes them often to the danger of dying from hunger, through lack of provision which they could easily possess in abundance if they would only take the trouble to gather.

Such a devil-may-care attitude toward provisioning mystified outsiders. In Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (1983), author William Cronon notes that to Europeans’ inquiries on this subject, the Indians would reply: “It is all the same to us, we shall stand it well enough; we spend seven and eight days, even ten sometimes, without eating anything, yet we do not die.”

"I was ever of opinion, that the honest man who married and brought up a large family, did more service than he who continued single and only talked of population."--Oliver Goldsmith

Feasting today though famine loomed tomorrow, as foolish as it seemed to outsiders, bespoke of something of the cunning of nature. Cronon identifies Native Americans’ willingness to endure lean times as a method of keeping lean also their tribes’ numbers. “The ecological principle known as Liebig’s Law states that biological populations are limited not by the total annual resources available to them but by the minimum amount that can be found at the scarcest time of the year.” Small numbers meant a small impact. “By keeping population densities low,” Cronon continues, “the food scarcities of winter guaranteed the abundance of spring, and contributed to the overall stability of human relationships in the ecosystem.”

Recipe for Thanksgiving Cake from The West Bend Cook Book (1903): "2 cups sugar, 2/3 cup butter, 3 eggs, 1 cup sweet milk, 2 teaspoons baking powder, 3 cups flour, 1 teaspoon vanilla, Divide the batter and add to one part -- 1 tablespoon molasses, 1 cup raisins (chopped), 1/4 pound citron (chopped), 1 teaspoon cinnamon, 1/2 teaspoon cloves, 1/2 teaspoon allspice, Little nutmeg, 1 tablespoon flour, stirred in fruit. Bake in layers and put together with currant jelly, alternating the light and dark layers. Cover with white frosting. Very nice."

Geographer Carl Sauer observed that by the mid 20th century Americans still had “not yet learned the difference between yield and loot.”

That white colonists found baffling the Native Americans’ seasonal austerities bespeaks of the fact that the colonists’ own system encouraged the opposite approach. “They assumed the limitless availability of more land to exploit,” Cronon writes, “and in the long run that was impossible.” This impossibility has yet to impress itself with any urgency, obscured as it is by industrialized farming practices and Monsanto-ized crop yields. Yet nature will see to it that the heedless fall captive to their folly, leaving them, like the Jemison family, with nothing to eat or drink.