You've undoubtedly heard the Audrey Hepburn mini-essay she composed when asked for her beauty tips. It begins, "For attractive lips, speak words of kindness," and goes on in that vein ("For beautiful hair, let a child run his or her fingers through it once a day"), culminating with "The beauty of a woman grows with the passing years. You can read the whole thing here, along with a right honorable debunking of the idea that Audrey Hepburn penned it. (She didn't, nor did she ever claim to, but she did recite it often; in fact, it was penned by a Borscht Belt comic.)

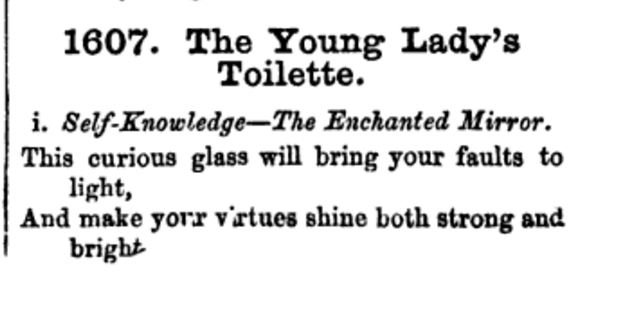

Certainly the idea that beauty is goodness isn't a new one; for much of history, we've equated beauty with moral goodness, the idea being that what is beautiful is good, and vice versa. But still, I was surprised to run across what basically functions as a precursor to "Hepburn's" quote, in a collection of household recipes and life tips from 1869:

(If that's too small, here's a link to the original.)

The book this is from, fancifully titled "Enquire Within Upon Everything," was a sort of 1860s lifehacking guide, instructing readers on everything from vegetable pickling, making wax leaf impressions, and stain removal to card games and social dance moves (if you want to improve your valse à deux, look no further). It dispenses morsels of moral wisdom throughout, but still this bit on "The Young Lady's Toilette" seems a hair random. In short, it's a more poetic version of the "speak words of kindness" bit. To wit: "Truth—Fine Lip-Salve: Use daily for our lips this precious dye, They'll redden, and breathe sweet melody." This bit of verse is surrounded by recipes that constitute "real" beauty tips—recipes for hair dye and facial milks—making it read, to this modern viewer, a bit flip, like, "Yeah, yeah, be good and all, but then do the real nitty-gritty."

I'm not going to get into the "what is beautiful is good" thing here, at least not right now—philosophers have been trying to determine its truth for centuries and we still flip-flop all over the place on it—but it is interesting to me to have a bit of evidence that we have a long history of trying to inject morality into what's otherwise a pretty straightforward collection of beauty advice. Victorian-era morality reinforced this, of course, but we're still eager to ameliorate the equation of beauty and vanity with that of beauty and goodness. But we're not particularly eager to replace the former equation with the latter. Cynically speaking, there's profit to be made from keeping vanity at the fore; if beauty is only goodness, what happens to Maybelline?

But less cynically speaking, if we did allow ourselves to believe that what is beautiful is good, we'd be cutting off a source of entertainment—which is what so much of beauty culture is, particularly when its adherents manage to rob it of wrist-smacking. Beauty-as-goodness might seem like it's a relief of the beauty imperative, but what's more wrist-smacking than the idea that you'd be prettier if only you were a better human?