Pictures from The Railroad Trainman, Volume 22 (1905)

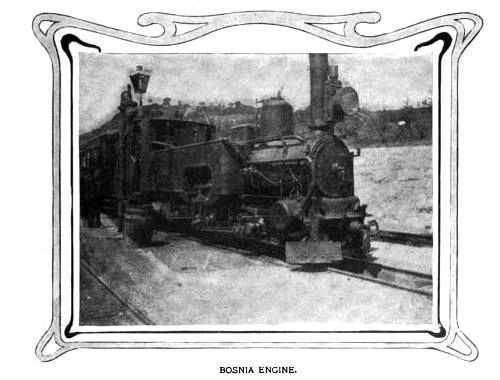

At one time Bosnia boasted the best railway system in Europe. Only the Orient Express offered better service

"In America the trains do not whistle, but bellow like a young calf" -- "London to the Rocky Mountains," (1873)

. Extensive in reach, its five hundred miles of narrow-gauge line ran from Montenegro to Serbia. No fewer than eighty tunnels burrowed through rugged mountains. And what the railway could not burrow through, it ascended, its trains pulled by herculean locomotives.

You would expect a ride on such a modern marvel to command a steep fare. But passengers rode cheaply. The government decreed that distance by kilometer would determine the price of the ticket, upon which station agents affixed stamps in two languages. Passengers tended to ride second and third class -- even the wealthy; the plush appointments of first they believed to harbor germs. Eminently legible signage announcing stations meant that you could ride without care. And you could hop on and off trains as you pleased; no stern conductor stood by to prevent you.

The railroad's popularity owed to the genius of its design. Each year it conveyed over mountain and plain one million persons and a million tons of freight.

The Bosnian railroad did lack such luxuries as express service, dining cars

The Baltimore and Ohio management has from time to time been adding special features to its dining car service," a 1922 issue of B and O Magazine reports. "The new menu includes such summer-time dishes as cold consomme, salads, sandwiches, sliced tomatoes, ham, [and] other meats."

Recipe for Turkish coffee from Charles Martyn's How to Make Money in a Country Hotel (1901): "[This] can be brewed from any high grade coffee pulverized to the consistency of flour. To so pulverize it. procure a Turkish coffee mill (costing about $3.50). Then for each cup of Turkish coffee take a heaping teaspoonful of ground coffee and a heaping teaspoonful of pulverized sugar, place in a Turkish coffee boiler (which is simply a long-handled saucepan lined with tin), with the necessary quantity of cold water, and bring to a boil (while stirring) three consecutive times. Serve in small cups without handles set in a holder of filigree brasswork or hard metal silverware. Small coffee spoons are used."

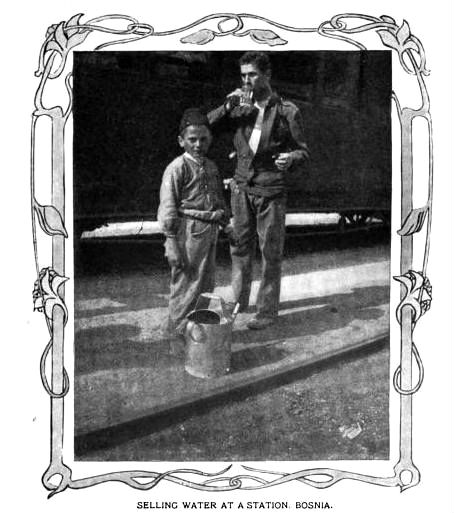

, and even drinking water. But these deficiencies presented little inconvenience. As to the moseying pace, passengers came to relish it, preferring it to rapid shuttling from burg to burg. As to the lack of refreshments, passengers compensated for this by bringing on board meals prepared elsewhere. Most brought their own lunch, and when thirsty they either drank from bottles brought from home or looked to the small boys parading along every station platform hawking tumblers of water.

The bureaucracy responsible for this miracle of modern transport called home a yellow brick and stone building located in Sarajevo. There officials knitted their brows over how to improve their cherished rail service. In their minds public good trumped profit. Planning sessions could run for hours. To gird themselves for these, railroad officials downed coal-black Turkish coffee served by a stalwart man in a fez. From caffeinated palpitations flowed the most innovative engineering breakthroughs, and the people of the Balkans no doubt appreciated the dedication of railway bureaucrats who would forgo sleep to see their trains reach places no one believed possible.