For this talk, I am going to use Facebook’s recent design change to its like button — we used to “like” things on Facebook; now we are permitted one of six “reactions”— as a way of getting at some larger points about identity construction on social media as a form of labor, and the role the idea of “authenticity” plays in extracting that labor.

From Likes to Reactions

A week or so ago, Facebook rolled out a much-anticipated update to its interface that expands the ways users can respond to other content within Facebook. Before, you could comment on something, or if that was too much trouble, you could simply like it with a click. Or, of course, you could scroll past it with no response, a passive choice that Facebook nonetheless tracks.

Now, however, users have an intermediate option between comment and like: When you hover over the like button or hold it down with your finger, you’re invited to further specify your intended reaction from a menu of six: Like, Love, Haha, Wow, Sad, and Angry. A seventh option called “yay” was killed late in testing because its intended meaning was perceived as “too vague.”

Facebook reportedly settled on these five added reactions after surveying what the most common one-word comments on newsfeed posts were, and after consulting with social scientists about how to accurately taxonomize the “range of human emotion.” So the company’s methodology was essentially reductive rather than generative from the outset: its assumption is that humans experience a limited set of emotions and Facebook need only reflect that with a concise emoji set. This is unlike actual emoji, of which there are more and more being developed, and which can be combined or deployed to express new shades of emotion that there aren’t even words for.

The Official Position

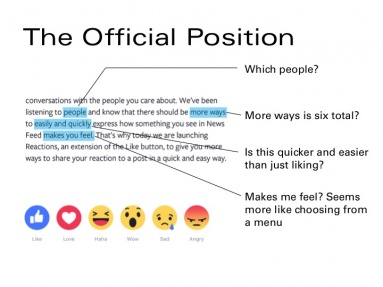

Facebook describes Reactions as giving users what they’ve been asking for. Here’s what the company said in announcing the change: “We’ve been listening to people and know that there should be more ways to easily and quickly express how something you see in News Feed makes you feel.”

That sounds almost benevolent. But it’s worth examining that statement more closely.

With Reactions, Facebook seems to be imagining a pretty straightforward process: A user sees a piece of content; experiences a specific, discrete emotion that they can clearly identify; and then they “quickly and easily” choose that particular reaction from the menu of clickable buttons.

But every step of that process is riddled with complication. Nearly every word in that sentence warrants further consideration. The “people” they are listening to are not just users but other advisers and researchers. The “more ways” to react is actually a limited set, premised on the notion that users would rather click a button than use language to express their feelings. And one’s feelings about some piece of content are typically a mixture that one may not be able to sort out: Maybe jealousy is mixed with congratulations; joy mixed with anxiety; a sense of discovery mixed with a sense of shame. The design of Facebook’s Reactions repudiates the possibility of such ambivalence, suggesting mixed feelings are abnormal, atypical. It presumes we have an immediate, precise response.

As several commentators have pointed out, the new Reactions feel more constricting and prescriptive than the Like button ever did. A Like, when it was the uniform currency of attention in Facebook, had a certain ambiguity: It could be spent on anything. But the greater precision of these Reactions says you can spend your attention in only six ways.

Accessing the Reactions menu does not make using Facebook easier or quicker, but more cumbersome. Rather than the binary process of saying yes or no to “liking” content, users now have a two-step process in which they decide to “react” and then pick a reaction. Then they have to get to the menu itself — a few seconds, but an eternity by Facebook’s own standards of time management. After all, this is a company that rolled out Instant Articles because it believes a few seconds is too long for users to wait for content.

Reactions and Decisions

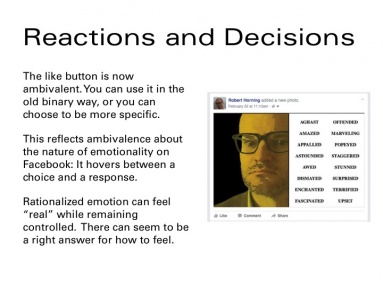

So why is Facebook willing to risk slowing its users down with Reactions? Why is the company undermining its own beliefs about our implacable impatience?

Part of it is because finding out who will work those extra milliseconds to react is useful demographic information. Since the Reactions menu doesn’t appear right away, users happy with the old way of liking can basically ignore them. This lets Facebook learn what sort of people are willing to invest more attention to what they are seeing in their News Feed, who thinks more about it regardless of whether they react. And, more obviously, Facebook gets more precise data about what emotional labels its users apply to what content, and how all that correlates to other user behavior, refining the company’s portrait of users’ interests and susceptibilities. For that database, whether the label corresponds to any actual feelings — whether users are actually angry about what they label as angry — doesn’t really matter. It just connects patterns of responses.

Adding the extra options basically allows Facebook to extract more information about all users and more labeling work from some of them. But beyond being a means for extracting more labor, Reactions, at the conceptual level, provides users with a kind of comfort zone for emotionality while the are on Facebook. The menu of affective possibilities suggests that responding to content in Facebook floats somewhere between a “reaction” and a decision. The specific, limited choices on the Reaction menu don’t really need to reflect users’ pre-existing responses — it works more like a poll that produces a reaction at our point of contact with the interface.

But the idea that with Reactions we are clarifying our “real response” lets us cling to the illusion that our “real responses” are rational and easily communicated in the first place. Reactions tries to sustain the impression that your emotions are deliberately chosen without their becoming a matter of strategic calculation or emotional manipulation. You are not simply broadcasting what you think you are supposed to feel, but genuinely responding.

In that extra moment of consideration that Reactions require, a useful space of fantasy opens up in which we can believe that the News Feed inspires us with a series of real feelings, when in fact we are suspending whatever complicated feelings we might have for the relief of just clicking a button. The fantasy is that we can experience total emotional control in the face of other people’s lives. Having predefined reactions helps keep users from overreacting, from acting out, from lashing out.

Reactions offer the promise that Facebook is a safe place where we won’t ever be overwhelmed by unwanted feeling. This way, we can play the game of guessing what reaction someone was hoping for without feeling entirely cynical. It is reassuring to believe there are right answers, right ways to feel.

The Purpose of Like

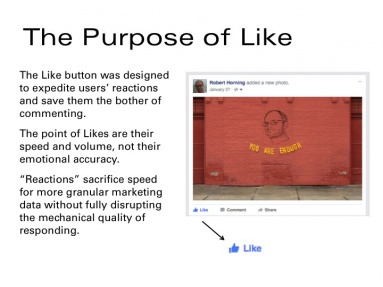

It used to be that Like was always the right answer. But with Reactions, Facebook is attempting to balance the Like button’s original mission, which was to radically simplify and amplify users’ impulse to respond, with the expectation of its clients — the advertisers — that it gather more comprehensive data about how users feel.

The Like was initially removed friction from online interaction. It normalized the idea that generic, binary responses could stand in for other forms of reciprocity. The quickness trumps accuracy or further elaboration of the potential complexity of those responses.

The point is not to allow you to express yourself or your “true feelings,” if there even are such things. In fact, the genius of the Like button is in that it absolves users of the need to have true or complex feelings. Instead it supplies an automated, uniform positivity that attempts to preclude hostility or disliking, or any sort of intense, considered emotional engagement that might interrupt a user’s flow on the site.

Likes thus encourage a kind of mechanistic sociality that is more akin to slot-machine gambling than to anything that risks reciprocity: You post some content, pull the handle, and see how many likes come out. Or, from the other side, you rhythmically sprinkle Likes over people’s posts like some benevolent Johnny Appleseed of social approval. The faster I can register a reaction to content, the faster I can put it behind me, and the more content I can process. I can still get into a satisfying rhythm of data processing, consuming more content and registering more and more reactions.

Reactions move a half-step away from that protocol, sacrificing some speed for the collection of more granular marketing data. The gamble is that Reactions will still save users enough of the trouble of interpersonal engagement that they won’t begrudge the extra cognitive burden.

Formatting the Self

The Like’s importance makes it plain that Facebook is not really in the business of “connecting the world” so much as formatting the world as data: It survives as a business by building marketing profiles of its users from who they connect with, where they go, what they look at, and what they like. When we consume content through Facebook, that consumption is simultaneously self-production, in data form.

All this information then guides Facebook’s algorithms in determining what ads and content gets shown in users’ news feed, and what content gets suppressed. Our standardized reactions to content are meant to make us machine-readable.

Facebook’s data-fying mission is reflected in the pleasures it gives to users: that of sociality as convenience. By giving our connections and interactions a particular, efficient shape — a predictable, routinized quality — it offers emotional deskilling as a kind of energy conservation, as the joyous opportunity to consume more content on our own terms. Facebook Reactions allow us to quickly exchange a few permissible emotions without requiring us to expend the energy required to actually believe we feel them.

Autocannibalism

By representing our personality as so many digital punch cards, the Likes and Reactions allow Facebook to generate of simulacrum of ourselves that anticipates how we might react to future situations. This can create a hermetic feedback loop, where past actions fully dictate future potentialities, foreclosing the possibility of surprise or change. That is part of the pleasure Facebook brings.

When the algorithms parse us, shaping what we see and what is served to us, they make us into a product we can ourselves consume —we become auto-cannibals. We get to enjoy how well Facebook has stereotyped us and feel known, recognized. And when it predicts poorly, we can take comfort in how that proves our ineffability, our rich complexity. It gives us an alibi for what we consume — it wasn’t my fault, the algorithm made me read that. Or we can defiantly redefine ourselves in opposition to the algorithm, letting it shape our identity in the inverse.

In any case, as the repository of so much information specific to users — both volunteered data and data collected surreptitiously — Facebook becomes increasingly central to how they conceive of their identity.

Entrepreneurial Subjectivity

This gives Facebook users all the more reason to tend to their profiles. This labor may at first be rationalized as personal expression of self-development, but social media’s saturation with metrics quickly makes the work far more entrepreneurial.

The numbers we rack up — of friends, of likes, of followers — make it clear how we can use social media to accumulate various forms of capital. These metrics provide believable proxies for your social capital (who you know, who listens to you) and cultural capital (what you like; the value of your tastes).

This work has become more and more mandatory, as it helps establish your reputation, likeability, hire-ability, social fitness, your sense of belonging.

Self-Consciousness and Self-Performance

The entrepreneurial mind-set that social media encourages brings with it a more intensified self-consciousness, a deeper awareness of how, thanks to Facebook, life is full of opportunities for strategic self-presentation. Such opportunities can begin to define the limits of what we conceive of as possible. If something doesn’t lend itself to becoming social-media content, we may not think of doing it in the first place.

Because social media supplies an ever-present audience that likes and reacts to everything, we have no sound reason not to always be performing for it. To the degree that we accept that social media is about our self-expression, this makes the self equivalent to and dependent on the impression we make on that audience. It doesn’t pre-exist these performances. On social media “realness” gets conflated with how many reactions we can generate. If we leave no impression on that audience, we have to begin questioning whether we exist at all.

Reconceiving life as a series of chances for strategic self-presentation in social media radically undermines the old idea of authenticity. “Authenticity” used to be spontaneous, disinterested feeling, not efforts to get attention. Authenticity was opposed to “selling out.” Now social media situate the self as always already “sold out,” in that self-promotion and attention-seeking have been normalized. Posting solely to get Reactions is not seen as aberrant or craven but natural. When we post content to social media, we are not necessarily trying to “be authentic” or “express ourselves” so much as we are communicating simply to see if people are listening (a point Bethlehem Shoals makes well here), to see if we are included. Luckily the algorithms are always paying attention to us.

Data Truth

Facebook’s algorithmic simulacrum of the self offers a compensation for any lost authenticity. It offers a new mode of authenticity through deeper forms of personalization: The more information you contribute, and the more of your behavior that is captured by surveillance, the more the platform can uniquely tailor an experience for you. This helps justify the way we are increasingly watched: all the surveillance reveals who we really are to ourselves.

In order to experience or inhabit that unique version of yourself, that “real identity” that your data has delineated, you have to keep using Facebook. To probe this self, we must consume and post more content, which triggers the algorithms to reveal that self’s contours. Hence, being “authentic” in social media essentially boils down to “post more,” “like more,” now “react more.” Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what you react to or what your specific reaction is: When the algorithms process it, it becomes “true to who you really are.”

The perfect reaction, the purest and most authentic reaction, has nothing to do with any content at all.