"Indicative of attempts to undermine the ICC process were the plethora of attacks against witnesses. This included intimidating, bribing, and killing them. The message being sent both by the state, which did nothing to protect witnesses and victims as required by the Rome Statute, and allegedly by the defendants and their supporters, was that if individuals cooperated with the ICC's investigations, they would pay heavy costs. Many did. As each trial date neared, more witnesses dropped out, thereby forcing the ICC to find others. This compelled the defense to ask for more time to review the new evidence, precipitating a vicious circle of delays and the need for more witnesses and more time. Politics began to trump the law as the defendants' political risk increased. Early on it appears there was a plan to eliminate, intimidate, and bribe people who knew too much about the PEV, key individuals who were part of it, and civil society activists who were assisting and sheltering potential witnesses. Leaving none to tell the story was an apparent tactic to get rid of key witnesses while simultaneously attacking the credibility of others. The aim was to get the cases dropped for lack of evidence even before the ICC's investigation began and charges were confirmed. Later, it was to destroy the credibility of other witnesses who remained and to delay or halt the onset of trials both before and after the 2013 presidential election. The deployment of violence emerged as an early pre-emptive measure even before the Waki Commission or the ICC entered the picture. Shortly after the end of the PEV, on 8 March 2008, Virginia Nyakio was murdered in a particularly bloody slaying. Nyakio was the wife of Mungiki's leader Maina Njenga, and might have known too much about Mungiki's involvement in the retaliatory violence in Nakuru and Naivasha, or have played a part in it herself. Two months later on 6 July 2008, Maina Diambo, Mungiki's Nairobi Coordinator, was murdered.37 On 5 November 2009, on the same day the ICC's Chief Prosecutor said he would ask the PTC to begin an investigation, Maina Njenga's deputy, Njuguna Gitau, was shot dead on Lithuli Avenue in Nairobi shortly after Njenga left jail.38 In March 2009, two members of the Oscar Foundation, a human rights organization, were killed a month after speaking to Philip Alston, the UN's Special Representative on Extra-Judicial Killings, about the murder of Mungiki members. In a May 2010 US Government Wikileaks cable, the United States Embassy in Kenya discussed “the steady rise in the number of individuals threatened or killed for apparent political reasons.” It said that former Waki Commission witnesses “ha[d] already been threatened.” The cable also spoke about the embassy's “multiple sources” who accused Kenyatta and Ruto of “directing a campaign of intimidation against potential witnesses.” It also alleged that Njuguna Gitau “may have been the lynchpin to channel funding from Uhuru Kenyatta to the Mungiki.”39 In the confirmation of charges hearings, the prosecutor noted that the above murders sought to eliminate individuals who had led the retaliatory attacks in Nakuru and Naivasha to keep them from implicating the organizers of the violence.40

The campaign to silence key potential ICC witnesses intensified immediately after Ocampo asked the PTC for permission to start a formal investigation in Kenya in December 2009, signaling a clear change in political risk.41 Civil society activists complained of witness intimidation. They cited unexplained disappearances, enticements to study abroad, and harassment by the National Security Intelligence Service (NSIS). They spoke of death threats to them and their families, and menacing telephone calls and text messages.42 A number of targeted witnesses went to the Kenya National Commission of Human Rights (KNCHR) for protection. The commission's vice chairman, Hassan Omar, attempted to help, but witnesses claimed they were in danger because a former KNCHR official had “leaked their testimonies.” The threats and attacks against potential and actual witnesses made the ICC's work increasingly difficult. Witnesses kept bowing out as each trial date neared and the pressure on them intensified something that continues up to now. In 2011, two individuals sheltered by Hassan Omar claimed he had bribed them and recanted their statements to the KNCHR and to the Waki Commission.44

As Susanne Mueller observed in "Kenya and the International Criminal Court (ICC): politics, the election and the law," the International Criminal Court must rely on the cooperation of witnesses who are, for the most part, located in Kenya, and so it must also rely on the government of Kenya to protect those witnesses from intimidation.

Much later in 2013, the ICC's witness no. 8 in the Ruto and Sang case used the same language and made similar allegations. He cited bribery by the ICC and retracted statements he had made both to the court and to the Waki Commission.45 Earlier, his family in Kenya said they were being harassed.46 The ICC itself had to drop its witness no. 4 in the Kenyatta case. Bensouda said he had lied and received bribes from Kenyatta's agents.47 She then dropped the charges against Muthaura, leading his lawyers to accuse the ICC of withholding exculpatory evidence. Bensouda retorted by mentioning other factors: lack of cooperation from the GOK, the intimidation of other potential witnesses who were too afraid to testify, and unnamed deaths. Kenya's attorney general filed a submission to the ICC's trial chamber rejecting Bensouda's claims.48 Since the 2013 election, there has been an increase in witness defection and worries about witness elimination. Witnesses are aware of the massive and powerful security apparatus available to Kenya's executive branch,49 and more witnesses have dropped out since the election. This includes 93 victims, described as vulnerable by their lawyer.50 In mid-July 2013, three other ICC witnesses in the Kenyatta case also withdrew, citing security concerns. They included: fear for themselves, their families, “insurmountable security risks” “too great to bear,” and worries about attempts to locate them.51 Following this, Ruto upped the ante by asking the prosecution for “screening notes” of ICC interviewees who were not even witnesses. Bensouda claimed this would jeopardize their safety.52 The overall intent has been to discourage any communication with the ICC and to strangle the court as the trial dates neared. The tactic is succeeding. Four witnesses in the Ruto Sang case suddenly withdrew in mid-September 2013 one day before they were to testify leading to an unscheduled postponement.53 A day later another quit before she was to testify in the Ruto Sang trial, citing fear and lack of security.54 This followed the outing of the first trial witness in social media. The ICC then called for her testimony to be held in camera and for special protection for witnesses. Bensouda said her office had uncovered evidence of intimidation and bribery by politicians, lawyers and businessmen who were doing to great lengths to cover their tracks and could face charges.55 Unlike domestic courts in advanced democracies, the ICC cannot effectively counter witness intimidation apart from issuing arrest warrants against the defendants and others. On 1 October 2013, the ICC issued its first warrant against Walter Baraza, a Kenyan journalist charged with bribing three witnesses in the Ruto Sang case. Bensouda claimed Baraza was “acting in furtherance of a criminal scheme devised by a circle of officials within the Kenyan administration,” and that the warrant was “an opportunity for the Kenyan government to demonstrate the cooperation they say they have been giving to the ICC.”56 In response, the attorney general asked Kenya's High Court to make a determination on the request. Legal experts called this evasive and said Kenya was legally obliged to hand over Baraza. Furthermore, continued intimidation amidst inadequate witness protection invites more dropouts and could be the death knell of the trials.57 On 19 December 2013, Bensouda asked the TC to postpone Kenyatta's trial until May 2014 after losing two key witnesses: one who refused to testify and another who lied. She said the case no longer “satisfy[ied] the high evidentiary standards required”.58

International law requires the government of Kenya to do so, and the ICC has no resources to do much on its ownn. However, since it is the government of Kenya, itself, which is on trial at the ICC--in the person of President Uhuru Kenyatta and Deputy President William Ruto--it should surprise no one that the government of Kenya has been lax in its "protection" of witnesses. One might go so far as to suggest that it has been the government of Kenya itself which is behind the campaign of witness intimidation that has all but destroyed the ICC's case, which is now on the verge of what seems like an inevitable collapse. In the six years since the post-election violence, witness after witness has recanted, disappeared, or died (and I have pasted Mueller's account of that steady attrition is in the right column). As the chief prosecutor recently admitted, at present, the case no longer satisfies the high evidentiary standards required to prosecute.

This process is, of course, the origin of the ICC Witness Project, the fact that an event which was witnessed by everyone--the Post-Election Violence which now goes by the cipher "PEV"--suddenly has no credible witnesses. Or, rather, everyone saw what was done to them, but no one now saw who did it. It becomes a thing that happened, apparently spontaneously: PEV just happened. Wikipedia tells us, for instance, that violence is like a volcano, dormant until it "erupts": "The 2007–08 Kenyan crisis was a political, economic, and humanitarian crisis that erupted in Kenya after incumbent President Mwai Kibaki was declared the winner of the presidential election held on December 27, 2007." Who can know why it does when it does? This was not a civil coup; things just violenced.

Courts and reports create their own realities: the world in which we must live comes into being through the ways we talk about and write about it, and through the letters and laws which our institutions create and maintain. In 2010, the ICC indicted Uhuru Kenyatta for crimes against humanity, and that transformed him into a particular kind of legal subject: he was now "the accused." He still is, technically, but another institution has, in the intervening years, made him into a different kind of subject: the chair of Kenya's Electoral Commission has declared him "president of Kenya." He cannot be both at the same time, and one will supercede the other: either he will be convicted, and (in theory) cease to be president, or he will be acquitted, and cease to be the accused. One of these realities will become true. The other will fade away.

Witnesses--if their truth was confirmed by institutions like the ICC--would produce one reality, in which Uhuru Kenyatta would become a criminal, not a president. In their absence, Kenyatta will cease to be indicted, and will simply remain president. Some of the ICC Witness poems are not witnesses at all, but un-wittnesses:

Witness #20 is an un-witness:

As is Witness #22:

As is Witness #22:

Yet if we observe the zero-sum calculation by which Uhuru Kenyatta is either president or criminal--the essential fact that he will either retain state power or become its subject--then we cannot regard un-witnessing as the absence of witnessing, but as testimony to the absence of witnesses. Un-witnessing is not only the witness's act of not-witnessing, in other words; un-witnessing is a violent act, a transitive verb with "witness" as its direct object. These witnesses have been un-witnessed, to put it in the passive voice; to put it in the active voice, someone has un-witnessed them.

To put it differently, since only one of two realities can become objectively true, un-witnessing is cooperation in the production of the reality in which Uhuru Kenyatta is president, not criminal. Unwitnesses do not simply decline to testify; unwitnesses testify to the fact that violence simply violenced, and in their self-negation, testify to the absence of the violence which suppressed their testimony. If a witness declines to be a witness, than she ceases to exist as such.

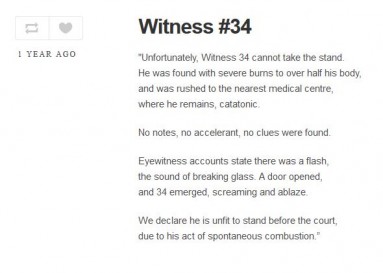

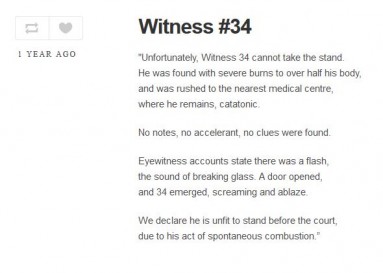

Witness #34 is an un-witness, for example, and so his voice does not appear in the poem at all: But his voice is not absent, even if his absence is being construed as "his act of spontaneous combustion," and being narrated as somewhere between an action he took and a thing that just happened, spontaneous. In fact, perhaps it's both: in the absence of an "accelerant," he must have done it on his own; in the absence of a note, the fire must have happened spontaneously. Yet the reality that emerges out of his catatonic silence is not silence, but speech: the declaration that he is unfit, a performative speech act which produces him as un-witness. We don't know who is speaking, of course; there is a "we" but it goes unnamed and unpictured. Which is exactly the point: the witness to the un-witnessing is also, in turn, un-witnessed, self-negating.

But his voice is not absent, even if his absence is being construed as "his act of spontaneous combustion," and being narrated as somewhere between an action he took and a thing that just happened, spontaneous. In fact, perhaps it's both: in the absence of an "accelerant," he must have done it on his own; in the absence of a note, the fire must have happened spontaneously. Yet the reality that emerges out of his catatonic silence is not silence, but speech: the declaration that he is unfit, a performative speech act which produces him as un-witness. We don't know who is speaking, of course; there is a "we" but it goes unnamed and unpictured. Which is exactly the point: the witness to the un-witnessing is also, in turn, un-witnessed, self-negating.

Previous:

As is Witness #22:

As is Witness #22: But his voice is not absent, even if his absence is being construed as "his act of spontaneous combustion," and being narrated as somewhere between an action he took and a thing that just happened, spontaneous. In fact, perhaps it's both: in the absence of an "accelerant," he must have done it on his own; in the absence of a note, the fire must have happened spontaneously. Yet the reality that emerges out of his catatonic silence is not silence, but speech: the declaration that he is unfit, a performative speech act which produces him as un-witness. We don't know who is speaking, of course; there is a "we" but it goes unnamed and unpictured. Which is exactly the point: the witness to the un-witnessing is also, in turn, un-witnessed, self-negating.

But his voice is not absent, even if his absence is being construed as "his act of spontaneous combustion," and being narrated as somewhere between an action he took and a thing that just happened, spontaneous. In fact, perhaps it's both: in the absence of an "accelerant," he must have done it on his own; in the absence of a note, the fire must have happened spontaneously. Yet the reality that emerges out of his catatonic silence is not silence, but speech: the declaration that he is unfit, a performative speech act which produces him as un-witness. We don't know who is speaking, of course; there is a "we" but it goes unnamed and unpictured. Which is exactly the point: the witness to the un-witnessing is also, in turn, un-witnessed, self-negating.