The Italian Futurists' marriage of man and machine was a feast for the senses

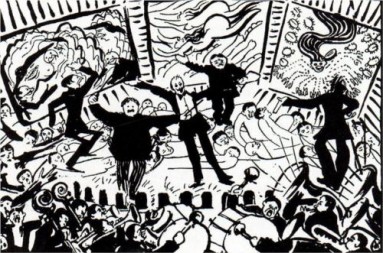

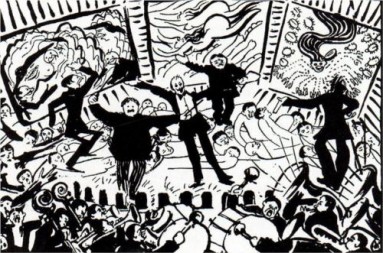

Umberto Boccioni, A Futurist Evening in Milan (1911)

"O my brother Futurists! All of you, look at yourselves! ... In the name of that Human Pride we so adore, I proclaim that the hour is nigh when men with broad temples and steel chins will give birth magnificently, with a single thrust of their bulging will, to giants with flawless gestures." --F. T. Marinetti

In a room whose walls are lined with aluminum, nimble waiters flit past diners, spritzing the air with perfume. A Wagner opera blares from a phonograph somewhere hidden. On each table sit four plates, each containing a small morsel. A quarter of a fennel bulb occupies the first, a single olive the second, the third holds a minute pile of candied fruit, and the fourth, a "tactile device" of red damask, velvet, and sandpaper, which the diners fondle as they eat.

That is what you would have encountered had you been dining at the Tavern of the Holy Palate on its opening night, March 8, 1931. An Italian Futurist restaurant, it astonished everyone; and as more of its kind opened across Italy, serving increasingly bizarre meals, the astonishment grew. Diners at the Bologna location were dubbed "experimental passengers," seated in a room that resembled a fuselage, and served dishes named for an airplane's various gear. Engine noises blared in lieu of Wagner. The experimental passengers came away from the experience unnerved and disoriented yet impressed by its beauty. "Too poetic to be appreciated by the needs of the stomach" one critic deemed the dinner. Another, awestruck by the spectacle of it all, believed he may have eaten "Bologna mortadella sausage, mayonnaise and the sort of Turin caramel know as pasta Gianduja," but after 24 hours and "careful examination of consciousness" he admitted he couldn't say for certain.

Luigi Russolo, Dynamism of a Car (1913)

The Futurists wanted their cuisine to discombobulate. They imagined the Tavern of the Holy Palate not as "a simple, ordinary restaurant," as Futurist luminary F.T. Marinetti writes, but as "an arts centre holding competitions and organizing Futurist poetry evenings, art exhibitions and fashion shows instead of the usual post-prandial coffee evenings or dances." They designed their eatery to disorder the senses, to unmoor the eater from his everyday habits. All of this discombobulating, disordering, and unmooring they believed advanced a risorgimento, a wholesale remaking of Italian thought and culture.

"Machines are worshipped because they are beautiful and valued because they confer power; they are hated because they are hideous and loathed because they impose slavery." --Bertrand Russell

The Futurists hated Italy as it was. They thought it lugubrious, dowdy, mired in the past. Its only hope lay in the glut of new technologies -- aircraft, steam engines, automobiles -- rolling off factory lines, all of which would transform Italy from a cultural and economic backwater to a modern international power. Marinetti's "The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism" (1909) celebrates, among other things, "greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents," "adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon," and "deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing." Buoyed by the machinic din, "multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals" would destroy "the museums, the libraries, every type of academy." Washed of its obsolete, moribund past, Italy could robe itself in the clean, efficient lines of the future.

"Before machines the only form of entertainment people really had was relationships." --Douglas Coupland

Despite their zeal for industry, machines, and automation, Futurists considered food one of the more effective weapons in the fight against tradition. Because it engaged the body immediately, it presented the fastest way of transforming the mind. And a mind transformed by modern food, the logic went, was a mind sympathetic to a modernizing agenda. "Though we recognize that great things have been achieved in the past by men who were poorly fed," writes Marinetti, "we assert this truth: What we think or dream or do is determined by what we eat and what we drink."

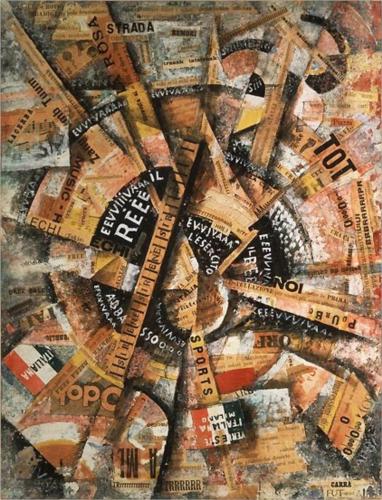

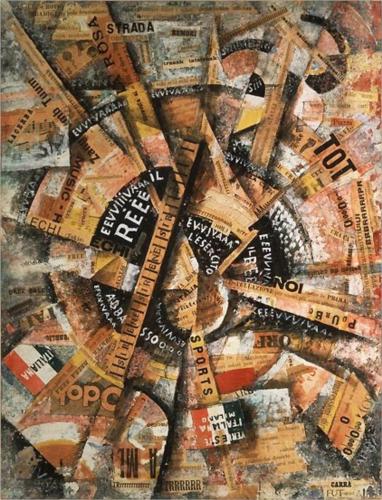

Carlo Carrà, Interventionist Demonstration (Patriotic Holiday Freeword Painting) (1914)

The opening scene of the now-lost film Vita Futurista features an old man eating a bowl of soup outside a restaurant in the Piazzale Michelangelo in Florence. He is accosted by a group of young Futurists, who berate him for patronizing the passé establishment.

It was clear that not just any old minestrone would do. A year after the Tavern of the Holy Palate's Turin debut the Futurists issued another characteristically unconventional publication. Part literary provocation, part user's manual,

The Futurist Cookbook offers a rollicking overview of Futurist gastronomy. Recipes such as "Taste Buds Take Off" (a soup of concentrated meat stock, champagne and grappa, sprinkled with rose petals), "The Excited Pig" ("whole salami, skinned") and "Carrot + Trousers = Professor" (a sculpture of a raw carrot standing upright to which two boiled eggplants are attached with a toothpick so as to look like violet pants in the act of marching) follow polemics on kitchen aesthetics and gastropolitics. The book promotes the use of such unusual equipment as ozonizers, ultraviolet lamps, autoclaves, and electrolyzers. It even contains a glossary for the uninitiated.

Conprofumo (with perfume),

contattile (with touch),

conrumore (with noise),

conmusica (with music), and

conluce (with light) -- each term captures a sensory affinity between seemingly disparate materials.

Contattile, for example, indicates "the tactile affinity between a given material and the taste of another," as in "the

contattile of the banana puree with velvet of a woman's flesh."

The Futurist Cookbook opens with an account of a Futurist who, fresh from a failed romance, sets about ending his life. A group of his friends arrive and distract him with a huge meal of "edible women." The intervention proves timely; devouring ladies he finds more satisfying than making love to them. The dinner fills him with newfound confidence and teaches him that the most important thing in life is the reproducible art of consumption. Beautifully crafted artificial foods satisfy desire and restore optimism. Whether the same may be said for sex is an open question.

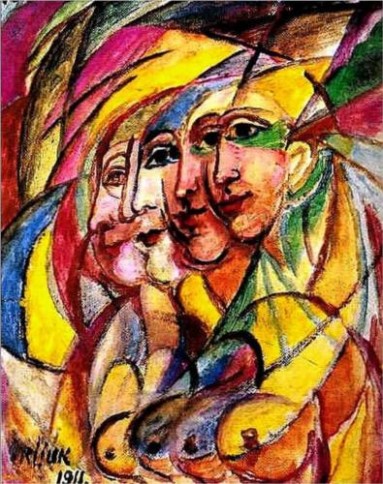

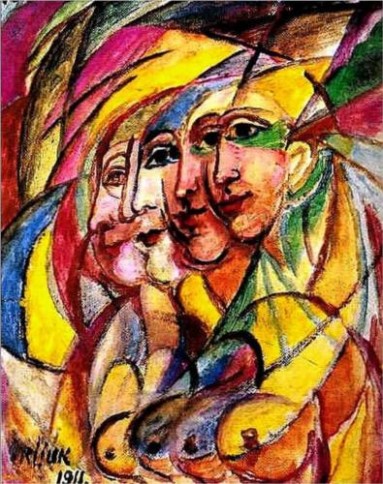

David Burliuk, Futuristic Woman (1911)

The perfect Futurist meal engaged every sense and piqued the imagination. The recipes (or "formulas") in The Futurist Cookbook attest to the care its authors took with food. A recipe for "Strawberry Breasts" calls for "two erect feminine breasts made of ricotta dyed pink with Campari with nipples of candied strawberries." Additional fresh strawberries hidden under the ricotta create a consistency evocative of "an ideal multiplication of imaginary breasts." "Chicken Fiat," a dish served at the Tavern of the Holy Palate's grand opening, requires equally complex preparation. A good-sized chicken is boiled, then roasted. After its removal from the oven, a large cavity must be dug in the bird's shoulder and filled with ball bearings. In the bird's rear go three slices of raw cockscomb. Returned to the oven, the bird bakes another ten minutes or "until the flesh has fully absorbed the flavor of the mild steel balls." The resulting dish is every bit as modern and invigorating as an Italian car.

You also know, my love, the gray disease / of our century, that makes us go on dying / day by day, as though from the blue heights / we'd loosed the ballast of our joy, / and now the lightness sears the heart of us. / Mild sentiment of a benumbed bourgeois / wrapped in furs that never can be paid for: / yearning for what cannot be, thirsting for infinity, / the fever of tomorrow. / Obsessions hammer at our delicate craniums as thin as the skulls of kittens. --Enrico Cavacchioli, “Let the Moon Be Damned” (1914)

No occasion was without its signature dish. In fact, Futurists invented occasions to commemorate with their outré cuisine. Soldiers about to get "into a lorry to enter the line of fire" or go "up in an airplane to bomb cities or counter-attack enemy flights" may wish first to enjoy a "Heroic Winter Dinner" consisting of three fairly involved dishes. First comes "Drum Roll of Colonial Fish," a mess of fish, bananas, and pineapples eaten to a snare's accompaniment. Then comes "Raw Meat Torn by Trumpet Blasts," a single cube of beef marinated in rum, cognac, and white vermouth, given an electric jolt, and plopped atop a bed of red pepper, black pepper, and snow. (The dish's presentation was meant to suggest an aerial view of a winter battlefield's trenches, corpses, and spilt blood.) Ripe persimmons, pomegranates, and blood oranges offer a palate-cleansing interlude before the meal's finale. Dubbed "Throat Explosion," it consists of "a pellet of Parmesan cheese steeped in Marsala." Immediately upon eating this "solid liquid" even the most reluctant warriors -- or "meat to be butchered," as the Futurists urged them to call themselves -- felt courage enough "to rush like lightning to put their gas masks on."

Umberto Boccioni, Dynamism of a Human Body (1913)

"All modern revolutions have ended in a reinforcement of the power of the State." --Albert Camus

The Futurist Cookbook celebrates conquest along with war. A guest at one of the Futurists' "Geographic dinners" would find himself in a dining room outfitted with aluminum and chromium tubing, as well as round windows looking out on "mysterious distant views of colonial landscapes." He would be seated at a metal table and invited to consult large atlases "while invisible gramophones play loud Negro music." A shapely young woman dressed in "a long white tunic on which a complete geographical map of Africa has been drawn in color" would then enter the room and invite the guest to choose his meal by indicating on the map "the city or region ... most seductive to [his] touristy imagination and spirit of adventure." A gesture to the waitress's left breast, over which is written "CAIRO," would amount to an order of "Love on the Nile," a dish consisting of a pyramid of palm wine–infused dates surrounded by "juicy little cubes of cinnamon-flavored mozzarella stuffed with roasted coffee beans and pistachios." After such refection it was hoped that the guest should find himself eager to conquer "continents, regions, and cities."

For all the exotic ingredients, natural or otherwise, found in the The Futurist Cookbook, a rather common regional one is conspicuously absent. In the December 28, 1930 edition of the Italian newspaper La Gazzetta del Popolo, Marinetti and his associate Luigi Colombo (better known as "Fillia") published a manifesto of Futurist cooking. In it they mounted a vicious attack on pasta. The stuff was inimical to the body assimilated to a world of steel, they wrote; it fills stomach without energizing the body, leaving the eater heavy, shapeless, and inducing in him "lassitude, pessimism, nostalgic inactivity and neutralism." "An absurd Italian gastronomic religion," pasta yoked the country to its backward condition. "The danger and disgrace of ... this macaroni," complains another Futurist, Marco Ramperti, "has made us the butt of indecorous metaphors beyond the Alps." Ramperti goes on to insist that pasta is as toxic as it is disgraceful. "Swallowed down the way it is, spaghetti poisons us," he writes. "Our thoughts wind round each other, get mixed up and tangled like the vermicelli we have taken in." Those who would defend this farinaceous enemy of the people Ramperti likens to convicts serving life sentences and archaeologists carrying around ruins in their own guts.

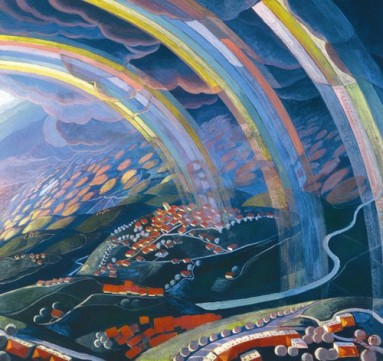

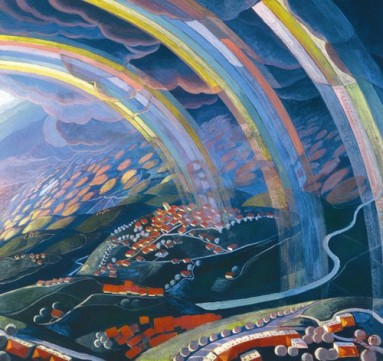

Gerardo Dottori, The Miracle of Light While Flying (1931)

"Study the past, if you would divine the future." --Confucius

Recipe for "Hunting in Heaven" from The Futurist Cookbook (1932): "Slowly cook a hare in sparkling wine mixed with cocoa powder until the liquid is absorbed. Then immerse it for a minute in plenty of lemon juice. Serve it in a copious green sauce based on spinach and juniper, and decorate with those silver hundreds and thousands which recall huntsmen's shot."

The Futurists' war on pasta scored few victories. In the city of L'Aquila housewives defended their love of spaghetti with a collective letter of indignation addressed to Marinetti, and the mayor of Naples protested that the "angels in Paradise eat nothing but vermicelli al pomodoro." Yet the Futurists anticipated that their cuisine might not find wide appeal. "Italian Futurism will face unpopularity again with a programme for the total renewal of food and cooking," Marinetti wrote. "Against practicality we Futurists therefore disdain the example and admonition of tradition in order to invent at any cost something new which everyone considers crazy." But Marinetti was just a man ahead of his time. The current craze for low-carbohydrate meals, so-called functional foods, and cheaply gotten (former) colonial fruits suggests that, were it in business today, the Tavern of the Holy Palate would require that reservations be made a year in advance.