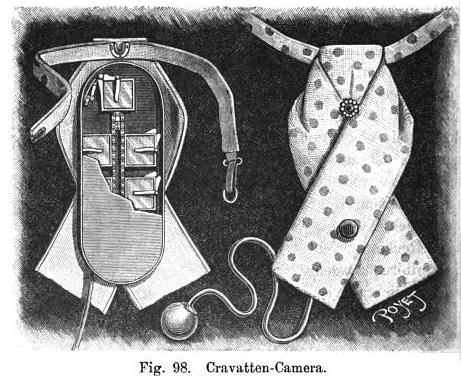

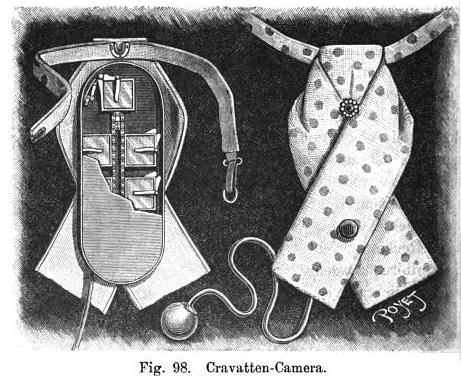

An illustration from Josef Maria Eder's La photographie instantanée (1888)

The narrator of Henri Barbusse's 1908 novel Inferno (L'Enfer) spends his days and nights peering through a chink in a boarding room wall. He cannot help himself, he protests; for as a man unmarried, rather short, with no children (and, he adds, with the intent that he "shall have none"), as a man with whom "a line will end which has lasted since the beginning of humanity," he felt himself "submerged in the positive nothingness of every day."

He fills this positive nothingness by watching lovers couple

"Max Dessoir mentions that in Spanish pornographic photographs women always have their shoes on, and he considers this an indication of perversity." -- Havelock Ellis, Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1912)

, couples quarrel and old men die in the next room. He overhears confessions that make him question the existence of God. His knowledge of other lives eventually proves a burden. "I saw now how I should be punished for having entered into the living secrets of man," he reports. "I was destined to undergo the infinite misery I read in others.... Infinity is not what we think. We associate it with heroes of legend and romance, and we invest fiery, exceptional characters, like a Hamlet, with infinity as with a theatrical costume. But infinity resides quietly in that man who is just passing by on the street.... So, step by step, I followed the track of the infinite."

The author of The Rural Cook Book (1907) notes that in American boarding houses "pie is almost the only form of dessert, except a restricted range of puddings." This limited offering often has "unwholesome effects" on boarders.

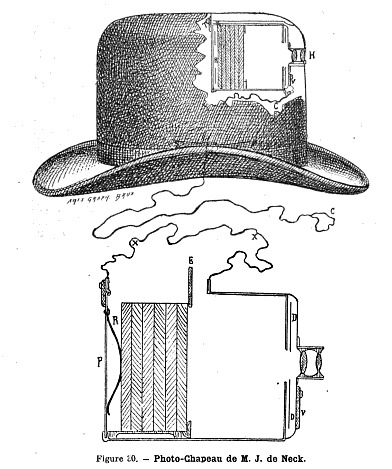

An illustration from Photographischer Zeitvertreib (1893)

The infinite misery of others is a pleasure compared to the misery of their absence. The narrator finds painful the hiatuses between lodgers. "Waiting had become a habit, an occupation" he says,"I put off appointments, delayed my walks, gained time at the risk of losing my position. I arranged my life as for a new love."

Only dinner in a poky dining room draws the narrator from his spot by the chink. What meals he ate he never reveals, but no doubt he consumed in haste, eager to return to his post. Indeed, Barbusse's

Inferno suggests that in some individuals the scopic and the appetitive drives burn with equal intensity.