By Kate Sheppard

In 1897, trachoma was classified as a “dangerous contagious disease” by the United States, and it remains the world’s leading cause of preventable blindness. Despite working to isolate the bacteria that caused trachoma and successfully treating patients with the disease for over seven years, Dr. Ida Bengtson (1881-1952) is rarely connected to the disease or to the hospital that, in practice, she helped build. Taking a look at Bengston’s life and career demonstrates how women often perform essential foundational work in scientific research — and in building scientific institutions — yet are later overlooked in the rush to attribute a “cure” or “discovery” or “invention” to a single person, usually a man.

But during the Progressive Era in the United States, trachoma was so dangerous that infected people who were attempting to enter the US legally were sent back to Europe by the US Public Health Service (USPHS) to avoid spreading the disease. Popular Science Monthly devoted an entire issue to “Immigration and Public Health,” in which the magazine highlighted grave trachoma statistics. Significantly, the article reflected the era’s racism, warning against fraternization with groups who were then labeled as high risk for infection, such as Native Americans and Italians. The personal and financial costs of preventable blindness made finding the cause of trachoma and treating it a matter of urgent public health.

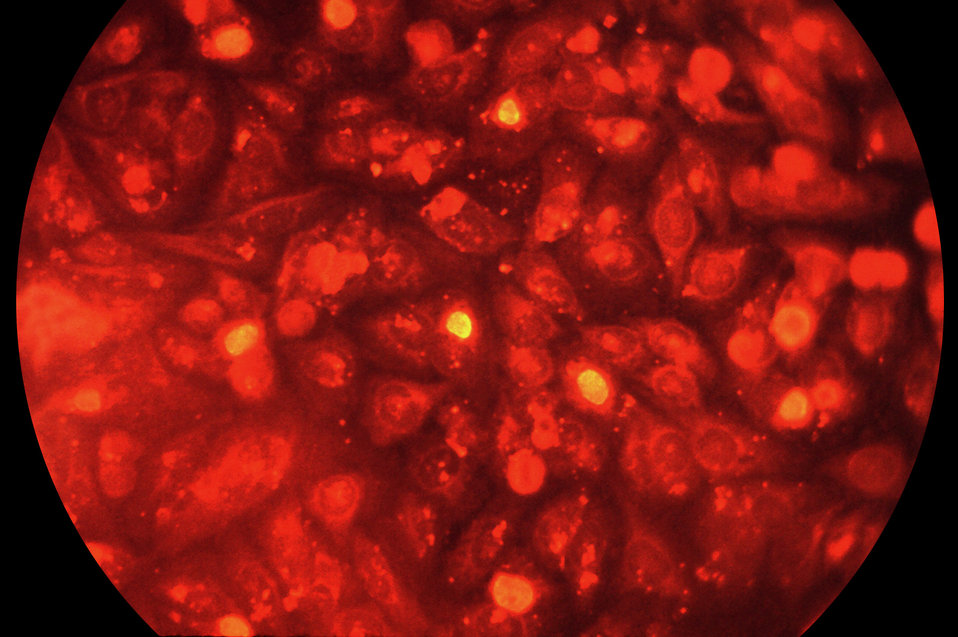

The reality was that no one really knew what caused the infection, how to stop it spreading, or how to treat it before it caused partial or total blindness. The disease was heavily spread throughout Alabama, Missouri, Tennessee, and Oklahoma, so isolating the cause of the disease for treatment would be a major public health victory. In the early 1920s, the Missouri State Health Department received generous funding from the Missouri State legislature to study and ultimately prevent trachoma infections, and to acquire land for a new dedicated hospital building in the town of Rolla.

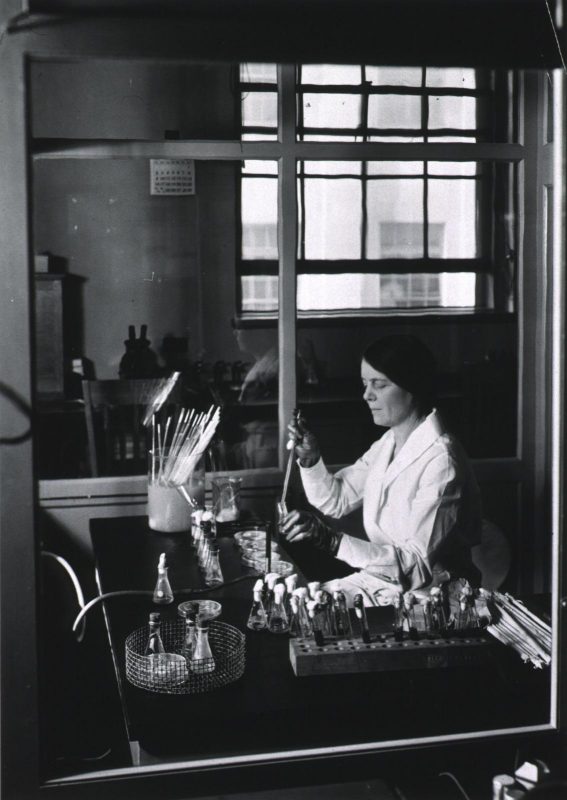

The USPHS sent their best bacteriologist to Rolla, Dr. Bengtson. Bengtson graduated with an AB degree from the University of Nebraska in 1903 with majors in languages and mathematics. She worked as a cataloger for the US Geological Survey in Washington, D.C. but soon realized that science was where her interests (and a higher salary) lay. She earned her MS in 1913 and PhD in 1919 in bacteriology at the University of Chicago while working as an assistant bacteriologist in the USPHS Hygienic Laboratory (now the National Institutes of Health). She was the first woman ever to work there, “filling her position so ably” that she paved the way for 10 more women to join over the next two decades.

She established herself as one of the country’s leading bacteriologists, demonstrated by the fact that the USPHS moved her wherever they needed her expertise the most. For example, in 1921, she was in Arizona leading a team of over 400 biologists in helping “maimed [World War I] soldiers regain control of injured members and deranged mental faculties.” She was also working on toxic anaerobic bacteria, such as Clostridium botulinum (the botulinum toxin), likely in conjunction with her work with soldiers and their wounds.

Dr. Ida Bengtson in 1925. 1926 Rollamo (Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy yearbook), p. 25. (Public Domain)

Bengtson’s precision and bacteriological successes made her a prime candidate to lead the charge against trachoma infection in the Ozarks; she arrived in Rolla in 1924. On top of her research duties, she was also appointed a lecturer in Bacteriology at the Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy (MSM), with a salary of $50 per month (around $712 today), on top of her USPHS salary of $150 per month (around $2140 today). She gave public lectures and regularly mentored women students at MSM. The December 11, 1930 issue of The Kansas City Star made light of her time with women students, calling it “entertaining,” but it is important to note that when men socialized with their (mostly male) students, it was — and still is — considered serious academic work. During all of this, Bengtson took her place at the helm of one of only four trachoma hospitals in the country. The hospital in Rolla was a small, wood-framed house on Elm Street, poorly equipped for treating the growing number of people suffering from this bacterial eye infection endemic to a broad swath of the mid-southern United States.

Former Trachoma Hospital, Rolla, Missouri. Photograph by Kate Sheppard.

Like many of her women scientist contemporaries, Bengtson built the foundation on which the newly-funded, and soon to be rebuilt, Trachoma Hospital operated in Rolla long after the USPHS moved her elsewhere. The Kansas City Star reported that in just six years of working with guinea pigs, monkeys, rabbits, and over 1500 human patients, Bengtson “made Rolla the chief American battle front in the war on” trachoma. She had worked to isolate the germ causing the disease, and in the process, she slowed the progression of the disease in over 1000 people. She and her team also helped the local population prevent the disease entirely by promoting good health and hygiene habits of washing hands and faces.

Yet Bengtson’s obituary only briefly mentions her trachoma work as a bridge to her groundbreaking Rocky Mountain spotted fever vaccines. Bengtson left Rolla in 1931 and, along with two nurses and six monkeys, arrived in Bainbridge, Georgia, to set up a new trachoma clinic there. The Macon Telegraph reported on February 10, 1931 that the community was scrambling for funds for a new building to house them and their work. It is unclear why or exactly when Bengtson stopped working on trachoma, but by 1939, the year the new red-brick hospital building was built in Rolla, and around the time when an effective treatment had been discovered and implemented using sulfonamides, Bengtson was working with a typhus unit. During that typhus work she found an effective vaccine for the tick-borne Rocky Mountain spotted fever. She retired in 1946.

Dr. Ida Bengtson. Photographer Unknown, National Library of Medicine. (Wikimedia Commons | Public Domain)

Around the turn of the 20th century, a number of women earned doctoral degrees, then went on to do crucial, foundational, quotidian work. Bengtson is just one of those women whose successes became the disciplinary scaffolding that others would build upon. She contributed to multiple urgent projects because of her drive, her expertise, and her precision. Bengtson and her contemporaries laid the cornerstones of multiple fields and research lines, but few look for those cornerstones, which make finding sources about them almost impossible. Bengtson’s work on trachoma demonstrates the value of not just looking for “Female Firsts” in science, but of understanding the breadth and depth of women’s contributions to multiple fields. Bengtson embodies the problematic gender politics of attributing credit only to an individual — especially when those individuals have historically been men.

Further Reading:

“Early Women Scientists at NIH,” The National Institutes of Health Office of History.

The author would like to thank Joy Lisi Rankin for her editing prowess; she would also like to thank Larry Gragg for the idea to write about Bengtson and for providing much of the material. Bengtson will be in Gragg’s forthcoming history of the Missouri University of Science and Technology (formerly the Missouri School of Mines).

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.