The meek shall inherit the earth -- if the mighty don't consume it first

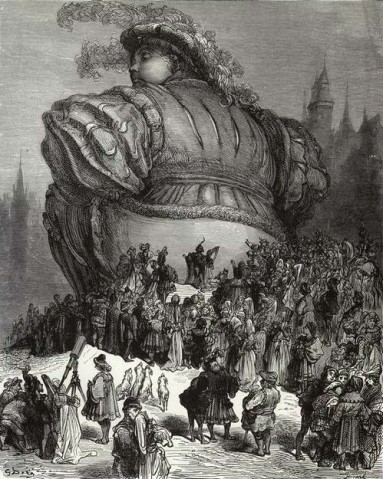

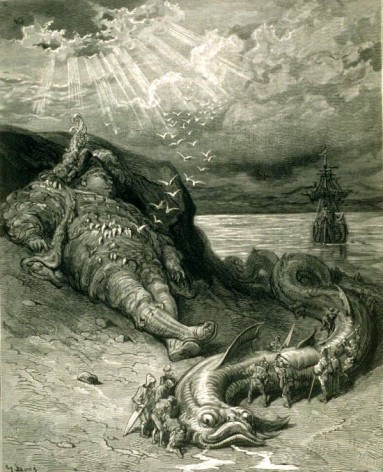

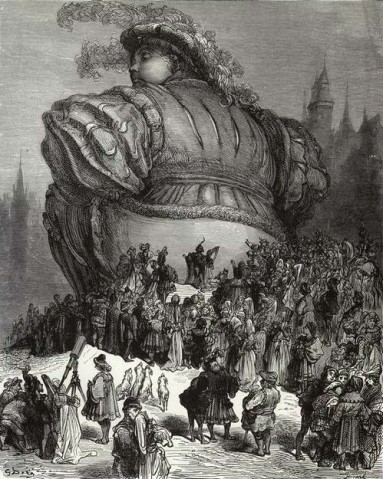

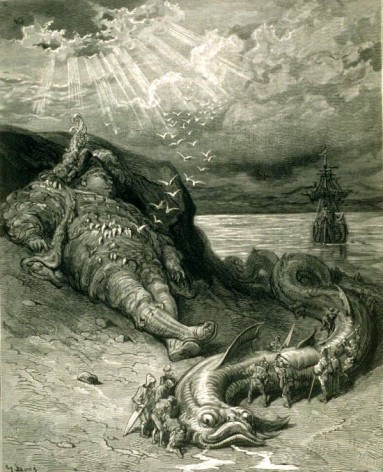

Illustrations from La Vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel (ca. 1873)

"What good can the great gloton do w' his bely standing a strote, like a taber, & his noll toty with drink, but balk up his brewes in ye middes of his matters, or lye down and slepe like a swine. And who douteth but ye the body delicately fed, maketh, as ye rumour saith, an unchast bed." -- Sir Thomas More

One midsummer evening in 1947 a Seattle policeman named Bill Hill entered a steak-eating derby. He decided this on a whim. His great appetite, he figured, made him a formidable contestant. In little more than an hour he wolfed down seven steaks and chased them with a strawberry sundae. When the derby official declared him the victor he blushed and said: "I could have eaten more, but I didn't want to show off."

"If there is anything sadder than unrecognized genius, it is the misunderstood stomach. The heart whose love is rejected -- this much-abused drama -- rests upon a fictitious want. But the stomach! Nothing can be compared to its sufferings, for we must have life before everything." -- Honoré de Balzac

Officer Hill's sense of just how far to take his gluttony perhaps owes more to his country's recent involvement in a world war than simple modesty, slogans endorsing game self-denial --

I'm a patriotic as can be -- and ration points won't worry me! and

Do with less so they'll have enough! -- likely still echoing in his ears. Had Hill lived 50 years earlier, however, and had he something more than a public servant's salary at his disposal, he may well have had shown less restraint than he did.

The well-to-do today jog, spin, fast, purge, slice and suction themselves into slim lines and supple contours; but obsession with remarkable geometry didn't always occupy their minds. To the voice that pesters people of modest means when reaching for a second slice of cake or the last lamb chop the well-to-do of yesteryear paid little attention. Conscience seldom stayed the bejeweled, fork-clutching hand. Captains of industry, men of business, women of fortunes, ladies of renown, magnates, prelates, the great and the good -- when they dined they brought appetites as vast as their wealth; and like that wealth, those appetites never seemed diminished.

Emperor Vitellius could not restrain himself from devouring the meat placed on altars as religious offerings.

That the rich ate in grand style and quantities comes as no surprise. History tells of Roman emperors who gorged from midday to midnight on the tongues of song birds and the bladders of fish and the soft, pink teats of heifers. Later kings and queens proved as voracious as their imperial forebears, as did prosperous merchants, burghers and other commoners. Anyone who had money made a show of it at table. A wealthy late 14th-century Englishman's ordinary meal consisted of three courses, the first featuring seven dishes, the second five and the third six. On festive occasions the number of dishes increased to nine, eleven and twelve, making for some thirty to forty plates of food in all. And this for a man of middling fortune!

"If the dinner is defective the misfortune is irreparable; when the long-expected dinner-hour arrives, one eats but does not dine; the dinner-hour passes, and the diner is sad, for, as the philosopher has said, a man can dine only once a day." -- Theodore Child, Delicate Feasting (1890)

Those with deeper pockets wedded spectacle to surfeit. One winter's night in 1476 the fabulously wealthy Florentine Benedetto Salutati hosted a banquet. He spared no expense. A first course of petite pine-nut cakes, gilded and doused in milk and served in small majolica bowls greeted guests. Eight silver platters of gelatin of capon's breast followed. Next came twelve courses of various meats representing the bounty of barnyard and forest: great haunches of venison and ham, a bevy of roasted pheasants, partridges, capons and chickens, all accompanied by thick slabs of blancmange. Fearing that his guests might weary of this parade of animal flesh, Salutati ushered in two live peacocks, their breasts pinned with silk ribbons and their feet affixed to silver platters. From their beaks curled tendrils of incense. Then came the

piéce de resistance: a large covered platter, also of silver. When Salutati's attendants lifted its lid, out flew a flock of birds.

"There Squire went on to lament the deplorable decay of the games and amusements which were once prevalent at this season among the lower orders, and countenanced by the higher: when the old halls of castles and manor-houses were thrown open at daylight; when the tables were covered with brawn, and beef, and humming ale; when the harp and the carol resounded all day long, and when rich and poor were alike welcome to enter and make merry." -- Washington Irving, Old Christmas (ca. 1819)

For all their inventive excess, the regal feasts of prosperous commoners could not match those of true royalty. England's Henry VIII, for example, boasted an appetite as invariable as it was insatiable. His favorite dishes he ordered to be brought to him, even when he journeyed abroad. Before visiting France in 1534, he dispatched a communiqué across the Channel. "It is the king's special commandment," it read, that all of the artichokes "be kept for him."

Joseph Stalin, it was reported, would become "very cantankerous" if served a substandard banana.

Other monarchs had their gustatory quirks. Soup France's Louis XIV slurped to the point of chronic diarrhea, and gluttony overtook him at his wedding feast to such a degree that he ate himself impotent (much to his bride's chagrin no doubt). Even the Revolution did little to discomfit the royal belly. So ravenous was the restored king Louis XVIII that attendants had to supply him with pork cutlets between meals.

The distaff side matched their male counterparts bite for bite. Catherine de Medicis, the Italian-born wife of France's King Henry II, regularly sickened herself on roast chicken and heaps of cibrèo, a thick Florentine ragout of rooster gizzard, liver, testicles and comb mixed with beans and egg yolks and served on toast. Britain's Queen Victoria too suffered unremitting peckishness. When Lord Melbourne, one of her ministers, advised her to eat only when she was hungry, she replied, "I am always hungry."

"The farmer is not a man: he is the plow of the one who eats the bread." -- Georges Bataille, Theory of Religion (1973)

Subjects expected their sovereigns to be hungry. Power rested on conspicuous excess. Abstemiousness occasioned distrust. In 888, Guido, Duke of Spoleto, a contender for the throne of the Frankish kingdom, found his bid derailed by his small appetite. Quipped the archbishop of Metz, one of Guido's critics: "No one who is content with a modest meal can reign over us."

"I went into the workhouse on Sunday last (April 30) after church.... I asked them [the inmates] how they lived, whether they had sufficient [food] ... they said, that if they could be allowed four ounces more bread three times a week, which was the day in which they had their pea-soup, they should have all they could wish for." -- The Parish and the Union; Or, The Poor and the Poor Laws Under the Old System and the New (1837)

Keen to emulate their antecedents, new money ate as voraciously as old. This was no more true than in nineteenth-century United States, where it seemed anyone who struck gold spent it on lavish refection. The American self-made millionaire, James Buchanan Brady, better known as "Diamond Jim," exemplified Gilded Age excess, breakfasting daily on beefsteak, chops, eggs, pancakes, fried potatoes, hominy, cornbread, muffins and a beaker of milk. Mid-mornings he snacked on oysters and clams. For lunch came more shellfish accompanied by two or three deviled crabs, a pair of broiled lobsters, a joint of beef, a salad and several fruit pies. To round out the meal and to make, in his words, "the food set better," he would polish off a box of chocolates.

When meals didn't "set better," they set decidedly worse. About the time that Diamond Jim was inhaling crustaceans by the dozen, a certain Mr. Rogerson (nationality and profession unknown) reportedly gorged himself to such a miserable extent that at meal's end he committed suicide.

"In the provinces bordering on Norway, the peasants called it the worst they had ever remembered ... a considerable portion of the people was living upon bread made of the inner part of the fir, and of dried sorrel... The sallow looks and melancholy countenances of the peasants betrayed the unwholesomeness of their nourishment." -- Thomas Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798)

Such tragic exceptions aside, the high life profited the individual living it -- and some believed that profit fell to the whole of society, as well. The British parson and social scientist Thomas Malthus insisted that the leisured class's appetites served the necessary economic end of eliminating surpluses to spur further production and thus increase profit. "[T]he specific use of a body of unproductive consumers," he writes in his 1820 book

Principles of Political Economy, "is to give encouragement to wealth by maintaining such a balance between produce and consumption as will give the greatest exchangeable value to the results of the national industry." Queen Victoria's abiding hunger, King Henry's ceaseless need for artichokes, Diamond Jim's lust for seafood, beef and milk, even Mr. Rogerson's morbid yen -- all did more than affirm status; they turned bread into gold.

Recipe for Financiere Ragout from High-class Cookery (1885): "Sliced Truffles. Scallops of Foie Gras. Cockscombs. Mushrooms, and Quenelles."

A wealthy man, Malthus could toast unproductive consumers as his own table he heaped with sweets and savories. But these men and women of appetite did more harm than good. The idea that potentates must gorge themselves excused the inherent destructiveness of their extravagance. Gluttony kills more than the sword, the saying goes -- a saying as true today as it was then.