[previous material/"part 1" here]

beneath and above this cantus firmus there run disordered exuberances

- Ernst Bloch

---

What is the relation between a sabotaged PS4 that never finishes booting up and the foreclosure of sabotage in a film whose Blu-Ray might get played on it, if only it would start? One way into this was hinted at before: the representation of a world split between competing regimes, or at least appearances, of technology, between craft and sheen, or the obdurate and the flickering. Indeed, the opposition at work in Elysium’s grimy keyboards vs. transparent tablets or in Oblivion’s yuppie-driftwood vs. inhuman triangles is hardly limited to those films. In other recent releases, it adopts the shape of an even more hackneyed contest, digital vs. analog.

In Pacific Rim, for example, the nominal divide between giant lumbering mounds of alien flesh and giant lumbering mounds of robotic metal gets parsed out further, because one of the central plot points derives from the gap between two kinds of “Jaegers” (those behemoth vehicle mounds piloted from within by humans, because, apparently, the envisioned future has forgotten about that whole drone turn in military affairs). There are new-fangled digital pseudo-Transformer Jaegers (used by everyone but the Americans) and there are old (2017), analog (albeit nuclear), and already decommissioned (sent to “Oblivion Bay” in Oakland) Jaegers, like “Gipsy Danger,” the Jaeger aligned with the protagonists, that still run off more openly mechanical processes.

In total accord with a yuppie logic that must veil all its choices behind false cries of necessity, the yearning for the simpler times of analog mechanized death gets the narrative excuse it needs. An electro-magnetic pulse from one of the aforementioned fleshy threats (the Kaiju) puts the next-gen Jaegers out of commission, leaving just ol’ faithful Gipsy Danger

Battleship, the other recent Transformers-with-more-water-droplets blockbuster, realigns that division into human-analog and alien-digital, complete with AC/DC bro jam accompaniment as weathered vets pulled out of retirement and hot young things alike rescue Earth from modular, hulkish, and bristling alien crafts with nothing but their standard-issue battleship and plentiful references to The Art of War.

All species can agree on haptic, smearable things...

All species can agree on haptic, smearable things...

Sure, the human battleship is “modern,” as a shot of Rihanna rotating gun turrets by twisting her fingers on what may as well be an iPad hint, a shot later echoed from the alien side as if to hint at common ground. But both that possible commonality of two battleships passing in the night and the prospect of successful algorithmic war are blown-away by the relentless insistence on human courage as the juncture of tough physical exertion with weighty, mechanical stuff. A representative sample: the sailors gruntingly lugging a 1,000 pound shell from one gun to another; the DIY-firing up of the battleship’s steam engine; a double-amputee vet beating the shit out of an armored alien through pure determination; and, of course...

outsmarting the invaders and their slick displays, targeting reticles, and tracking missiles/buzzsaws by literally turning the battle into a game of Battleship, as the sailors reveal that they “can track without radar” because they have mapped the entire theater of operation with that familiar grid from which the entire film is nominally derived. (i.e. “B-3…” “You sunk my cruiser!,” etc)

The film must have won an award in some alternate universe for most absurdly over-extended adaptation. It’s like making an opera version of Connect Four.

The film must have won an award in some alternate universe for most absurdly over-extended adaptation. It’s like making an opera version of Connect Four. None of this is especially unique, given that so much action cinema from the outset has turned on the idea of the out-gunned and out-manned beating foreign hordes by simpler means, elbow grease, and a generalized commitment to Freedom. What is different, though, is the stark opposition between this visual-narrative schema and the means by which it was produced: namely, through a massive exertion of the digital, with a heft of capital, time, and processing power that more than equals the towering fighters on display.

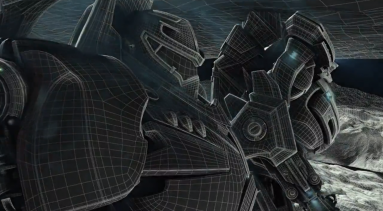

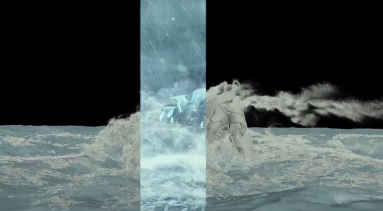

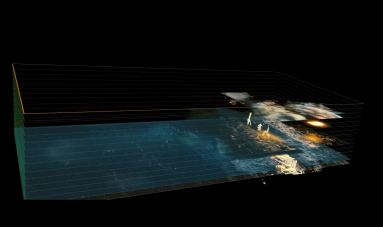

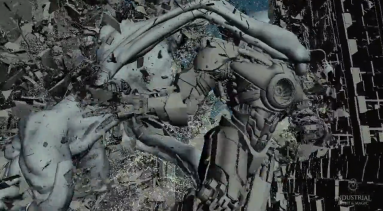

While Pacific Rim integrated certain “practical effects,” such as the construction of miniatures for destruction and the filming of actual smoke, particles, and water, Gipsy Danger, that triumph of the analog itself, was “built” digitally by Industrial Light and Magic (ILM), as were the others Jaegers and Kaiju. Skin, lighting, and damage effects are wrapped like infraslim panels over a gridded form, which then are tossed into and through similar objects (Kaiju, buildings) consisting of further panes, frames, and quantified volumes.

Gipsy Danger slams a Kaiju into a building. Render still.

Gipsy Danger slams a Kaiju into a building. Render still.

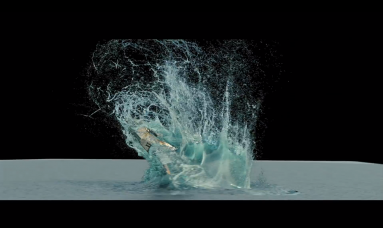

The resulting splinter and splatter move in accordance with calculations that crunch the interaction of phantom weight and velocity and attempt to randomize, within a restricted range, particle effects and debris so as to produce the appearance of the unpredictable contingencies of real matter on matter action.

The same goes for Battleship, whose visual effects were also helmed by ILM and its various “partnerships” with VFX teams and render labs far afield, including in Singapore. Digitally modeled water, ship, sky, and the explosive force of fired shells alike are set within a digital “aquarium” to calculate how they interact and slosh. Like the Jaegers, they are never filmed from any angle: they are set in constructed space and recorded from a chosen perspective after their movements have already been modeled, when they are merged with other elements shot or animated.

And so, even as a green-screened Charlie Hunnam swaggers toward his nuts-and-bolts counterpart and as echoes of old Ford “Built Tough” commercials flicker in my mental overlay, the actual methods of these images’ construction guts any validity of that nostalgia. It demonstrates the alleged split to be itself just one more camoufleur’s cladding applied after the fact to a mode wholly alien to available structures of looking and thinking. In trying to make sense of it all, we end only with a headache, the “suppressed, dull rage capable of being distracted”

Contrary to an old-fashioned ontological realist and sometimes fist-pounding emphasis on cinema showing the “real world,” my suspicions about this operation have nothing to do its supposed falsity or the idea that Del Toro somehow “betrayed” the nobility of men in rubber suits smacking each other around in front of a wind machine. My interest lies instead in the basic structure onto which that aesthetic preference for the hand-hewn, heftable, or photographed – rather than processed, calculated, and animated – has been applied. To think about the relation of such images to sabotage requires thinking first about the relation between those images and the process of their making. Because in this visual system, that process becomes pressingly apparent, even as the materials involved remain invisible, obscure, and beyond the grasp of those - myself included - who watch them. We know that the Jaeger is spun from the combination of a processor and a giant sum of labored hours just as much as we know that the particular techniques, decisions, patches, and tweaks are beyond our reach. We just know that it costs.

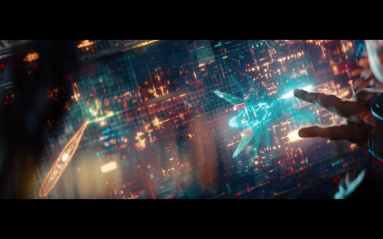

Tony Stark putters around amongst holographic corpses

Tony Stark putters around amongst holographic corpses

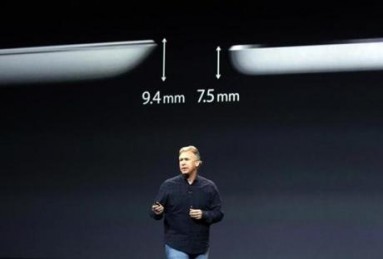

The connection - and distance - from sabotage becomes clearer when we track back from an animated leviathan fight to the machines that play that fight for us, because there too, the real links between how the device was made, how it operates, what it is supposed to do for us, and what it actually does are deeply obscured. To be sure, they are hidden in the way that any commodity, especially a mass-produced one, covers the explicit tracks of its path from rare earth to Foxconn to living room, but these images veil those passages even further. Consider the reigning object used to mark “advanced,” and potentially evil, technology in these films: the touchscreen, be it in Oblivion’s table-length tablets or Battleship’s tablets or the ubiquitous screens – be it in Elysium or Robot and Frank – of translucent glass in which information can appear and vanish without a trace or the furthest extension of barely-thereness, the holographic OS of Iron Man 3 that lets Tony Stark play goateed Sherlock in a neon charnal field.

Their real world correlates are hard to miss: tablets and phones in the baleful arms race to be ever thinner, ever lighter, and all approaching a fantasy point of zero where one will hold what weighs nothing and has no depth yet can still be touched, swept, and pinched. A screen untethered from both mass and history of manufacture, a window that does not even need glass to frame and show.

Budweiser's "Buddy Cup," which adds drinkers who chin-chin as friends on Facebook

Budweiser's "Buddy Cup," which adds drinkers who chin-chin as friends on Facebook

The underpinning logic of the absent tablet is itself just one facet of a historical dynamic felt daily, with a mixture of anticipation and creeping dread, by those who live in situations and zones of the globe where the need for touchable screens of various sizes might be felt, whether or not one has the cash to do anything about it. That dynamic is the increasing blur between things that can gather data and/or process it to be presented as information and things that cannot, that are “dark” to the world around them, even as they remain consumable, usable, or destroyable. In other words, one faces the increasing prospect of all elements of the built world becoming gatherers, processors, or transmitters, especially in ways that are not immediately visible to those around them.

For instance, if an arrow “communicates” with a wall by hitting it, that interaction and aftermath can be easily seen, heard, and felt. When an IDF “Smart Arrow” – I wish I was joking – is fired at a wall, those filmed cannot immediately detect that it is beaming back to their enemies a stream of images for up to seven hours.

That prospect that any and all things in our surroundings might be POVs, rather than elements of a space to be seen from our own, is thick in the air these days. All the world’s a spy movie when bugs do not need to be planted because they are come pre-built into the terrain, and when secret agents are just malware and remote-start tea kettles.

In short, sabotage is the name for the very prospect denied by Elysium and its fetish of objects that can be made and used yet not understood or altered, be seen as miraculous but not as secular. So to answer the question: the relation between such cinema and sabotage is a negative one. This cinema is the image of the historical negation of sabotage, or any thick knowledge of circulation’s routes and detours, during a long moment where it shows itself increasingly to be a necessary optic onto a world.

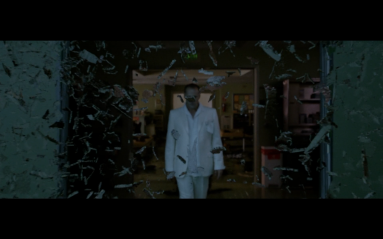

That negative image, the portrait of sabotage thwarted and foreclosed, is nothing so immediate as the image of a touchscreen-piloted drone with no discernible nuts and bolts to slacken, no exhaust port to piss in. It is de facto a more complicated capture, both a suspicion about the thickening world’s capacity to display and communicate information and the evacuation of the prospect of doing anything about it other than gawk. Still, it can be glimpsed in the form of one visual situation, repeated again and again in the large-scale cinema of the past decade to the point of becoming its authorless signature. It can be seen here, in Constantine (2005, dir. Francis Lawrence), when The Devil comes to Earth and decides to make a splashy entrance, so to speak.

Constantine, or the Devil walks through frozen time

Or this, from the forest escape scene in Sherlock Holmes: Game of Shadows, where the advance of time jerks back and forth from CSI-renactment creep of particles across empty space to Jude Law’s herky-jerky sprint:

Sherlock Holmes: Game of Shadows

Sherlock Holmes: Game of Shadows

Or this:

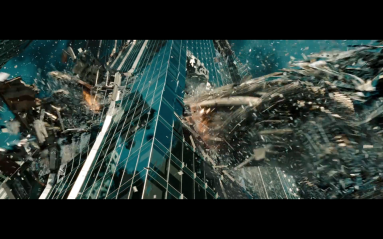

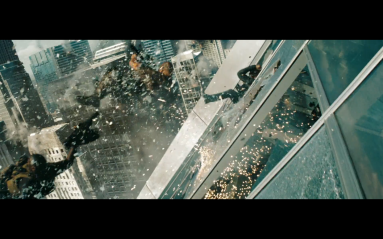

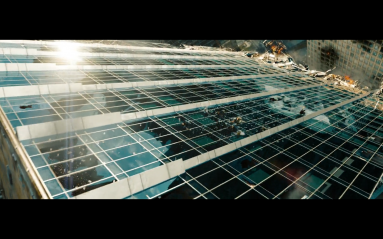

Or perhaps its most “advanced” recent display, in the third Transformers (Dark of the Moon), when a robot worm-python burrows through and then strangles a highly reflective skyscraper, cyberpunk’s mirror shades made architecture:

the smooth outside of which various characters slide before adding to the debris by following the film’s basic injunction - “Shoot the glass!” - to reenter the building.

In these and the plentiful other instances familiar to anyone who has seen a capital-intensive action flick in the last decade and a half, the recurrent obsession is to show the after-effect of one or more shattered surfaces, always in slow motion and often decelerated to the point of near arrest, as the manifold shards of whatever busted or falling material fill, hang, and splay in the air, clattering against each other and other elements of the scene joined together as animation. In short, it is the application of bullet time to all that exists.

To call these “surfaces,” though, is not to limit this signature image to moments where something as obviously shard-prone as a glass door is exploded into a perennially blue-lit ice storm by Lucifer. The situation is the same in the kind of particle effects/atomistic puke that a film like Sucker Punch loves, where ash, snow, fire, glass, wood, dirt, sequins, and spent shells jostle for space with unrepentant Orientalism and women themselves so buffed with filters as to become one more composite texture available for shattering.

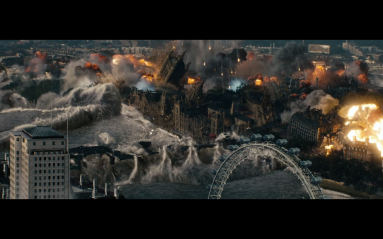

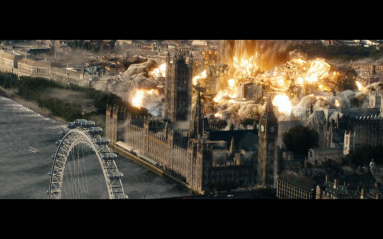

The prior entry in the series (G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra) had its own bravura feat of urbicide, letting “nanomites”

When the filmmakers turned over the shots to us they explained that they didn’t want to see the typical “nuclear blast” type shots. They wanted to surface of the earth to “shatter”. We explored the idea of treating the ground plane as a thick “shell” that would break like glass when the impact happens.

The effect is achieved, no doubt. However, the way this “shell” breaks is in accord with the breaks already there, because the construction of this destructable London involved a montage of “plates.” Having been provided with “helicopter footage over London to use as plates,” these modular slabs dictated both images of London: as unruined (the assemblage of various angles and excess footage into a manageable pattern of surfaces that would maintain their “properties,” both the houses on them and the relevant textures, in accordance with a hierarchy of “foreground and background assets with the foreground models being more finely detailed and the many background ones being more procedural”) and as midway through ruination (“This animation of the plates drove ALL the destruction and simulations that would follow”).

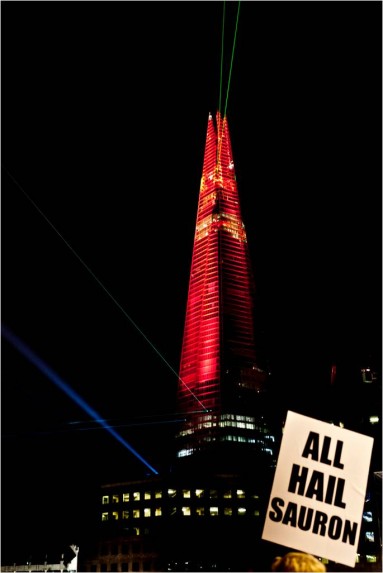

In this regard, it is fitting that The Shard tower – yes, the one that looks like a villain in one of these films, the one designed to be “a shard of glass through the heart of historic London” (in the words of its architect Renzo Piano), they one they inaugurated by cladding in Technicolor red light so it could be that heart’s dagger, the one where, in a moment of such non-simultaneity as to make Blochians weep with joy, a fox was found living in the unfinished hull, 72 stories above the street – was built in these years of this shard cinema and is nowhere to be found in this scene.

The reason is simple enough: The Shard opened to the public in February 2013 while Retaliation – slated to come out in June 2012, pushed back just to amp up promotion and convert to 3-D building wasn’t finished until February of 2013 – had its principal photography start in fall 2011. But by that fall, The Shard was already a good 801 feet high, missing only its last fifth of steel spire there to snag the tallest building in the EU prize. Yet in Retaliation, no Shard in sight, except in its absence, insofar as the first shot of London just prior to impact is from on high, angling northwest past the London Eye ferris wheel to the other side of the Thames: from, that is, a position that may as well be from the top of The Shard.

This is a POV onto the breaking of London into the plates of surface it was already constructed to be, from the top of a building that makes this very principle into architecture. Just a splinter bundled taut in surface, a glass scarf raised to heights achievable solely by gargantuan feats of capital, a thing nobody wanted from the start and resisting full occupancy because it was always the heart-staking that mattered anyway, a building already adequate to the unmaking it calls out for, joining the chorus of requests made to foxes or any other illegal thing.